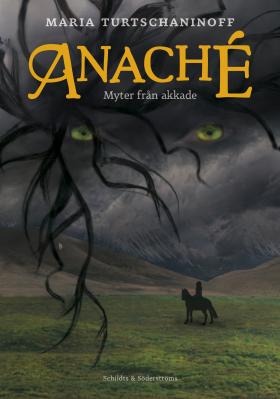

Anaché. Myter från Akkade

(Anaché. Myths of Akkade)

by Maria Turtschaninoff

reviewed by Agnes Broomé

In Anaché, Maria Turtschaninoff returns to the fantasy world she created for her award-winning second novel, Arra. But we no longer find ourselves in the country Lavora, with its dazzling capital and dark forests, but in the boreal lands of the Akkade, a nomadic people who roam the great northern plain with their sheep and horses, connected to the settled people in the south only through infrequent trade. The Akkade are organised into tribes, each led by a rouk or chieftain, and looked after by an angakok, or shaman, who communes with the spirit world and performs the rituals that safeguard the fragile balance between humans and nature.

The homeland of the Akkade is starkly beautiful and magically animated by the presence of gods, goddesses and the spirits of all living things, but it can also be a punishing environment, especially during the winter months when snow buries the grasslands and each isolated family struggles to survive. Akkade society can be equally harsh, shaped by customs that subjugate women, as evidenced by the frequent and brutal beatings Anaché’s father gives her mother, and by physical and magical forces, which are the only sources of power on the plain.

Anaché is the daughter of a rouk and a wilful, unusual child. Excluded from the training her older brother Huor receives, she secretly practises skills reserved for men, such as riding and knife throwing. Though only her mother knows it, Anaché has also been favoured by Pa Jau, the spirit of the mountain goat, during her long hours alone on the wide plain. Even so, as she nears her coming of age ritual, her sula, Anaché is increasingly confined to the homestead, where she must await being married off, unable to escape the fate of every Akkade woman. Life seems to be taking its inevitable course. But something dark is happening among the Akkade. Yurok, the new shaman of Anaché’s tribe, transgresses against nature by refusing to conduct the sula of a young girl. This act of misogyny is a crime against the balance between the God and the Goddess and it sets in motion a chain of events that threatens to annihilate the people of the plain. As the Akkade gradually succumb to a never-ending winter sent by the slighted Goddess, Anaché emerges as the chosen one, the only person who can end the suffering of her people and return balance to the physical and spiritual worlds. But in order to do so, she must not only defeat the powerful Yurok, but transgress every law that binds men and women and transform herself and the Akkade.

Turtschaninoff has crafted the world of the plain and its people with great care, making it reminiscent not only of real nomadic people and their environment, but also of the shamanistic tribes often glimpsed at the periphery of high fantasy. Once again, Turtschaninoff succeeds in creating an environment realistic enough to feel almost familiar and true to the reader, yet so richly infused with magic and originality that something new and unexpected always seems to be just around the corner.

With Anaché, Turtschaninoff confirms her ability to constantly reinvent herself; her previous books are all clearly related, but each has a distinct mood and voice of its own and takes the reader to an entirely new place. Nevertheless, some of the most important features of Anaché reflect typical characteristics of Turtschaninoff’s authorship. Most prominent among these is perhaps the author’s choice of protagonist: a young, disenfranchised girl who chooses to take on a great responsibility, who breaks rules to claim her inherent abilities and who is charged with saving the entire world.

Also, like previous novels Arra and Underfors, Anaché is a powerful coming-of-age story that does not shy away from difficult questions of sexuality, responsibility and gender identity. Indeed, in Anaché many of these issues come to the fore with unusual force. Particularly compelling is the use Turtschaninoff makes of her by now familiar subversive boy/girl pairing, which pitted step-siblings Emmi and Martin against each other in De ännu inte valda (The Not Yet Chosen Ones) saw Arra rescue a prince in distress and win a kingdom, and gave Underfors the dual narrative voices of Alva and Joel. In Anaché, the expected twosome consists of siblings Anaché and Huor, but a twist of fate makes the relationship infinitely more inventive, challenging and tragic, allowing Turtschaninoff to sharpen and extend her feminist critique to new sites of conflict.

With each new book she writes, Turtschaninoff’s voice grows stronger and clearer, and with each new book I have the pleasure to read, I become more convinced that she is one of the Nordic region’s most interesting writers of youth fiction. I can only hope that she will allow us many more journeys into the painful, rich and enchanting world of Arra and Anaché.

Anaché. Myter från Akkade

Schildts & Söderströms, 2012. 389 pages.