Den stora kreditfesten. Historien om Klarna

(The Big Credit Party. The story of Klarna)

by Jonas Malmborg

reviewed by Anna Paterson

By the 2010s, Klarna – a Stockholm-based company selling ‘payment solutions for online trading’ – was growing so fast it attracted international attention, even in the overheated atmosphere of financial technology at the time. The idea was to adapt the seductive ‘Buy Now – Pay Later’ option to the internet age. The obvious risks made established operators doubt not only the project’s morality as well as its profitability. Jonas Malmborg, an experienced financial journalist, tells a complex story with verve and insight.

Back in 2005, three business students at Stockholm School of Economics convinced themselves – if not many others at first – that an online option for buying on credit would please both suppliers and customers. The market was ready for an option that seemed quicker and safer than entering your card details for each purchase and, arguably, more ‘European’ than PayPal.

Of the three young men, Sebastian Siemiatkowski was the guiding spirit and a born entrepreneur whose role model was Ingvar Kamprad, the austere creator of IKEA. Siemiatkowski grew up in relative poverty, unlike his colleagues, market analyst Niklas Adalbert, and ‘numbers man’ Victor Jacobsson. All three benefited from an excellent education, a single-minded focus on their new business idea and a seemingly inexhaustible capacity for hard work. All of which was needed as they built their company on a Buy Now and Pay Later (BNPL) model. At the time, the Swedish public tended to be financially risk-averse – generally, ‘debt’ was a boogey word.

On the other hand, technical solutions to problems have always appealed to the Swedes. By now, Sweden had a startlingly successful record in digital enterprise. In a marketplace dominated by the USA and China, this small remote country rated third in a famous 2013 survey of ‘unicorns’ – a Silicon Valley term for newish (not more than 10 years old) companies valued at one billion dollars or more. The leading ones are household names by now: Klarna, Skype, Spotify and the video game developers Mojang (Minecraft) and King (Candy Crush). Storytel is up and coming, as one of the world's largest subscribed audiobook and e-book streaming services.

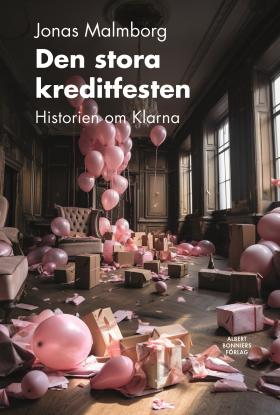

But the book’s clever cover image – a messy after-the-party scene that is also an extravaganza in pink – hints at other crucial elements in the ‘story of Klarna’. The pinkness takes up the advertising themes from the later reiterations of the company as it launched itself internationally (5000 employed in 45 countries, so far) and, especially, in the USA. Its image-makers presented consumerist fantasies with a pink theme, centered around celebrities: think Snoop Dogg in an ankle-length fur surrounded by servants in pink kaftans. Meaningless but funny and attractive images to sell the idea of a credit company specialized in encouraging consumption of fashionable stuff – a digital shopping platform (Klarna Checkout) which is also an obliging online bank.

The other aspect of the image, the post-party feeling, is only partly true but, at times, Klarna has hovered on the brink of serious trouble. We learn of episodes of bad behaviour by senior people, and tensions between the founders which eventually led to Sebastian Siemiatkowski being in effective charge. Klarna has been castigated in the media for errors of judgement and for potentially breaking the Swedish law on staff negotiating rights (MBL).

But the company is still growing, despite currently being in the red. Its millions of customers now generate dataflows, which in themselves are worth very serious money. Klarna’s algorithms know who you are and can predict when you will shop, how much you can be persuaded to spend and what you are likely to buy. This appeals primarily to advertisers, but Klarna, like its leading competitors (PayPal, Stripe) gains by having its customers tied to the company by transactions. Subscription-based platforms (Spotify, Netflix, Storytel; Amazon’s services) also rely on captive customers. Smart phones and the rapidly expanding app culture strengthen such dependencies.

The story of Klarna’s growth entails instructive and fascinating technical discussions which are too complex to review here. Overall, the non-expert reader cannot help wondering at the future effects of the trade revolution that has taken place over the recent couple of decades. Shops and cash are disappearing, replaced by computer screens, digital charging and delivery firms. Malmborg discusses, perhaps too cautiously, the environmental wear-and-tear and dubious morality of global businesses using their firepower to stimulate consumption. The fact has not gone unnoticed by the next generation of internet entrepreneurs: internationally, there are several comparison websites with SaaS (Software as a Service) components, aimed at informing and channeling customers towards sustainable, low carbon-intensive products.

Will the goodies win? Malmborg briefly discusses legal regulation and control of the online marketplace, but his conclusion seems to be that the modern state can, in the end, be sidelined. It is a central argument in his important, informative book: real wealth is accumulating in a technocratic world that exists in parallel with the modern state, with its unending lack of funding for public services.

Den stora kreditfesten. Historien om Klarna

Albert Bonniers förlag, 2024

303 pages

Foreign Rights: Leo Lagercrantz, Lagercrantz Agency

Jonas Malmborg is a journalist and documentary filmmaker whose engagement in how financial and social planning affect people is clear in his novel Fältöversten (Bonniers, 2012) – the name of a shopping and housing development in central Stockholm which is the focus of the story’s gang of disaffected teenagers.