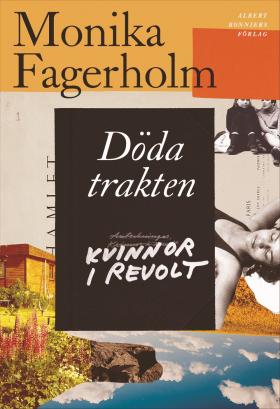

Döda trakten. Kvinnor i revolt

(Nowhere Land/Women in Revolt)

by Monika Fagerholm

reviewed by Darcy Hurford

In 1972, the filmmaker Chantal Akerman made La Chambre (The Room), which lasts around 11 minutes. True to its name, it shows a room: the camera slowly pans around it in two 360-degree shots. Then there’s a third shot, which unexpectedly stops half-way through and moves backwards to show a young woman eating an apple. Stealthily, gradually, the viewer is shown a succession of still lives: the kitchen, the stove, a kettle, some fruit, and a bed, on which the woman appears the second time around. Not a film with much of a plot, certainly, but plot isn’t the point. By its slowness, La Chambre builds up an atmosphere of suspense: you wonder what it is building up to. The repetition is an effect too: what you see the second time is not entirely identical to the first; when you see it for the second time it is coloured by the experience of seeing it before.

Monika Fagerholm’s novel Nowhere Land / Women in Revolt is also set in the 1970s, starting in the summer of 1976 but moving around freely in time, and repetition is a large part of the way it is told. It’s a technique Fagerholm has used in earlier novels, from Wonderful Women by the Water and The American Girl onwards, where certain phrases are repeated again and again, taking on different nuances in the context and the fact of their frequent repetition. Nowhere Land develops this further and to at times quite uncomfortable effect. To give an example: Alice moves from the countryside to live with her father Max and his other family in the suburbs near Helsinki. Her stepmother, Siri, is happy about this, her half-brothers Jakob and Michael less so, but none the less it is all reasonably amicable. Then a young woman is found murdered in the forest nearby. The manner of her death is described in a few sentences. About fifty pages later, the same event is described in almost the same wording. And again fourteen pages after that, at which a reader catches themselves thinking this? again? before it registers that something horrible is being made to somehow feel more banal through being repeated. The shock and tension are no longer there; the third telling is not the same as the second or first.

There is little tension in Nowhere Land, as the back-and-forth way it is told means that most plot developments are mentioned early on; the main thing is how it is told and what happens in the meantime. It is intended as the first part in a trilogy, however, so it makes sense that there are some loose ends. One is Alice’s half-brother, Jakob, starring in a production of Hamlet at the start of the novel but vanished in (appropriately) Denmark by the end. Another is his brother Michael, so over-functioning and successful you wonder what’s behind it. The character who seems most likely to be appearing in a later book is Honecker (a nickname), a young woman that Alice meets and ends up working with over the summer with a mysterious American called Tim and later seems to be studying law in Sweden.

Honecker is the link to the background events frequently referenced in Nowhere Land: the Baader-Meinhof terrorist group and its offshoots that had been creating fear in Germany at the time. A fear enthusiastically stoked by governments and media alike, it is suggested here. The ‘dead zone’ of the prison in Stammheim where Ulrike Meinhof, Gudrun Ensslin and others were held is the ‘döda trakten’ of the novel’s Swedish title. Honecker is also a part of what makes Alice start to write, ‘like a little animal’, and parts of the novel are actually stories-within-stories: extracts from Honecker’s notebooks and from Alice’s novel The Girl at the Boarding School, about a girl drawn into political activity and suspected of terrorism. It sometimes feels hard to tell who is writing what, but that is slightly beside the point. Another part of Alice’s emergence as a writer is Veronica Segers, a mentor figure who holds house parties, Alice’s boyfriend Pelle and her friend Evelyn, an unsuccessful poet. Nowhere Land is very much a bildungsroman about developing creatively. And, like the succession of still-life objects that feature in La Chambre, it sets out a whole range of cultural references, from Adrienne Riche, Doris Lessing, Saul Bellow, Hagar Olsson and Kafka to the Sex Pistols, Abba, Chet Baker and the obligatory Bowie (is it possible to write a novel set in the 1970s without namechecking Bowie?). There is a lot going on and yet it feels like it is preparing the ground for its successor.

Döda trakten. Kvinnor i revolt

Förlaget (Helsinki) 2025, Albert Bonniers förlag, 384 pages

Foreign rights: Salomonsson Agency

Monika Fagerholm is one of the most prominent Swedish-speaking writers from Finland. Several of her novels have been translated into English, including Underbara kvinnor vid vatten (Wonderful Women by the Water, translated by Joan Tate), the August Prize-winning Amerikanska flickan (The American Girl, translated by Katarina B. Tucker) and the Nordic Council Prize-winning Vem dödade bambi? (Who Killed Bambi? translated by Brad Harmon).