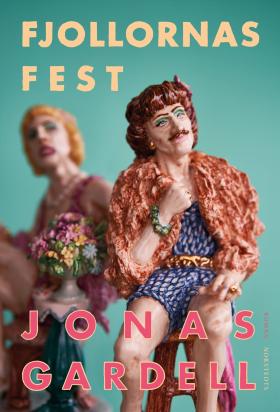

Fjollornas fest

(Sissy)

by Jonas Gardell

reviewed by Mia Österlund

As few others, Jonas Gardell has blazed a trail for the depiction of the history of gay men. His trilogy Torka aldrig tårar utan handskar (Don't Ever Wipe Tears without Gloves), portrays the AIDS epidemic from the view of a chosen family of gays, foregrounding the stigma that surrounded the new disease.

The year 1971 is essential in Swedish gay history as the year when a younger generation began to demand increased openness and gay liberation. Gardell’s novel circles around one night, 29 July, when Club Etoile opened on Kungsholmen in Stockholm, immediately attracting hundreds of partying gays. Among them are a group of scorned queer characters, the sissies Jeanette, Francis, Nana, Bettan, Kajsa-Marie, Gunilla, and Christina.

Within around two hundred pages, Gardell tells at least three parallel stories. Firstly, the legendary sissy party at Club Etoile. Secondly and thirdly, the story of Mikael as a young boy raped by a paedophile in 1978, followed by the story of a slightly older Mikael, who joins the sissy community at Club Etoile in the 1980s and hears the sissies’ stories about the legendary party in 1971. The book is divided into five sections: ‘The Red Shoes’ in which Mikael’s father reads him H. C. Andersen’s fairy tale at bedtime; ‘The Sissy Party’, a lengthy depiction of Club Etoile’s opening night party; ‘The Strange Man’, recounting the rape and including the perpetrator’s backstory; ‘The Mountain’, where Mikael is introduced to the gay scene; and finally, ‘The Mirror Images’, which deals with the family silence surrounding Mikael’s rape, as well as his coming out.

Back in 1971, the sissies partied hard. Hence their jargon is riddled with talking-back strategies, such as calling each other bitches (‘slynor’). They tend to get sentimental and tell the same stories over again, remembering what the gay community used to be like, and how they met up in secret in public urinals and parks back in the 1950s and -60s. Their rowdy laughter barely covers the palpable pain behind their anecdotes of loss, lack of love and brutal violence. Gardell draws on authentic testimonies from members of the sissy community. To tell their story grounded in the spectacular opening night party of Club Etoile is a brilliant idea. Unfortunately, though, Gardell hurries through their stories too quickly and as a result, the characters remain bleak and hard to tell apart. Moreover, all the gay characters – regardless of what generation they belong to – speak in the same peculiar manner, as if they were actors in a Swedish film from the 1940s or 1950s.

The sissies’ own stories serve as a multi-voiced background, or as a choir of vulnerable gay lives, mirroring Mikael’s story. Despite the loud partying and the rough jargon, this history of homosexuality leaves the reader with a taste of despair and darkness, as if happiness was never an option for the sissies.

Young Mikael – Gardell’s alter ego in the novel – recapitulates memories of being girly, and hence a sissy. When a boy, Mikael misunderstands his mother’s warning about strange men who offer candy as an alluring future promise. At the age of 14, an older man grooms and rapes him. This sexual assault is a central trauma in the novel and effectively related in fragments. Gardell has depicted this autobiographical rape trauma in previous books, but this time he adds the perpetrator’s background story. The man who grooms Mikael is a sailor, who acts out his paedophile desires when abroad.

In the 1980s, Mikael joins the sissy scene in Stockholm, where he encounters very little queer happiness and liberation. The sissies can still not be sincere with one another, dwelling on filth, humiliation, violence, rape and betrayal, unable to express and receive real affection.

Gardell paraphrases Andersen’s fairy tale, in which those who wear the red shoes must dance until they die. The fairy tale works as a dark reminder that getting what you wish for may result in abuse and physical harm. Gardell also uses ‘The Pied Piper of Hamelin’ to tell a story of blind desire and defeat. The elevated style of the fairy tales brings colour to Gardell’s narrative, although they do not correspond that well with the overall story.

The sentimental prose of the gay community portrayed here can be read as a rebellious queer discourse. Dagens Nyheter’s critic Kristina Lindquist calls it ‘messy make up on someone who knows she won’t pass’. Gardell’s choice of narrative style is indeed a provocative choice, but I remain unsure whether it succeeds in its endeavour to tell gay lives. Giving the sissy a voice of her own is, however, no easy task, and Gardell must be applauded for trying. The book fits well into his larger project of re-humanising the effeminate gay man. Still, although much of Gardell’s earlier production within gay literature has paved the way for this volume, which clearly is a medley of earlier motifs, it does not meet my expectations.

Fjollornas fest

Norstedts, 2023

221 pages

Foreign Rights: Salomonsson Agency

Jonas Gardell is a comedian, novelist, musician and playwright who has published numerous novels and other works. Part 1 of Torka aldrig tårar utan handskar was reviewed in SBR 2013:1.