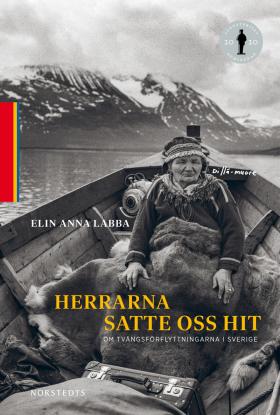

Herrarna satte oss hit: Om tvångsförflyttningarna i Sverige

(Sirdolaččat: The Deportation of the Northern Sámi)

by Elin Anna Labba

reviewed by Fiona Graham

‘Boundaries have always existed, but time was when they followed the edges of marshes, valleys, forests and mountain ranges. The new borders of the Nordic nations cut across all natural systems. They cut through pastureland, family ties, and migration routes that have been used for thousands of years. When land is partitioned, people are separated.’ Thus Elin Anna Labba introduces her account of the historical events behind the forced displacement – Bággojohtin in the Northern Sámi language – of Sámi reindeer herders that began in the early 1920s and continued through the 1930s.

Newly independent Norway, following the dissolution in 1905 of the union with Sweden, was keen to assert a national identity in which there was little place for those not regarded as properly Norwegian, like the nomadic Sámi. In the far north, pride of place was to be given to settled farming, rather than itinerant reindeer herds tended by a people who spoke an unrelated language and lived according to different customs. The reindeer grazing convention signed in 1919 by Norway and Sweden therefore provided for the mass relocation of Sámi families who summered on the Norwegian coast and wintered in Sweden. These people would refer to themselves as sirdolaččat – the displaced.

Many heads of families were instructed to sign boilerplate letters requesting authorisation to relocate to other Sámi communities further south in Sweden. The letters were not translated into Northern Sámi, and in any case relatively few reindeer herders were literate. They were told there would be land available for them. For many that was untrue. But the authorities took the view that nomads had no attachment to the land and could thus be moved around with ease. In their eyes, a Lapp was a Lapp (to use the old exonym rejected by the Sámi themselves).

In her remarkable book, Elin Anna Labba – herself the descendant of displaced people – gives multiple voices to the dispossessed. She supplements recorded material with interviews of her own, conducted with relatives of the sirdolaččat. There are stories of families who lost hundreds of reindeer on the long trek southwards, as mature animals were used to heading northwards in spring, towards the Norwegian coast. In many cases extended families were split up, being obliged to settle far from each other. In others, nuclear families unaware that the move was permanent left young children unable to travel with host families, believing they could pick them up a few months hence. All too often, the months turned to years, and sometimes the children were never recovered.

Beyond material loss and the breaking of family bonds, the dispossessed also lost vital aspects of their culture. Often they found themselves unable to understand the people in their new environment, be they Swedes or speakers of a different Sámi language. Both the interviews and the passages in which the author imagines the lived experiences of individuals documented in the historical record reveal the intense pain of being uprooted forever from a beloved landscape. This was particularly traumatic for a people so intimately linked to the natural world that for them islands, mountains and rivers were imbued with a spirit of their own. As the reindeer convoys headed south towards unknown country, people bade farewell to brooks and trails, thanking them for a lifetime of companionship. They would find themselves unable to greet the new landscapes by singing in the time-honoured yoik style. The passages evoking the severance of these ties are among the most heartbreaking in the book.

This mosaic of imaginative vignettes, interviews, historical documents, lyrical evocations of nature, and yoiks in the Northern Sámi language, accompanied by many striking photographs of Sámi people and their homeland, Sápmi, is truly ground-breaking. A depiction of a historic injustice, it is also a fascinating portrait of a way of life that has all but disappeared, and a tribute to a remarkable people.

Herrarna satte oss hit

Norstedts, 2020

190 pages

Winner of the 2020 August Prize (non-fiction)

Foreign rights: Catherine Mörk, Norstedts Agency

Elin Anna Labba is a journalist and former editor of Nuorat magazine. She now works at Tjállegoahte, the Sápmi Writers’ Centre in Jokkmokk.