from Ice

by Ulla-Lena Lundberg

translated by Thomas Teal

Thomas Teal's translation of the whole novel has been published by Sort Of Books.

This chapter, which may have been subject to slight change before publication, appears on the SBR website by kind permission of Sort of Books, Schildts & Söderströms, the author and the translator. The chapter has been made available online as bonus material to accompany the special SBR issue 'Cool Swedish Titles from Finland'.

from Ice

Chapter One

No one who has seen the way a landscape changes when a boat comes into view can ever agree that any individual human life lacks meaning. The land and the bay are at peace. People gaze out across the water, resting their eyes, then look away. There is nothing special to see. But in every breast is a longing for something different, and everything we long for comes by boat.

It’s enough that I am what comes, I, Anton, with the mail, for I may have someone in the cabin. Expectation sweeps across heaven and earth when they first catch sight of me. The landscape is no longer quiet, there is movement everywhere when the news goes round. Some are already running, shouting “Here they come!”

It is the same with those who, ancient and invisible, dwell beyond our range of vision. When a human being approaches, the air grows tighter, you feel how they crowd forward and want to know something about you—though you suspect that they no longer understand what it means to be alive, that they are no longer human, that the shapes you sense no longer resemble us. All the same, you feel their insistent desire to find out who you are.

Even though I have the throttle at full speed, we move slowly. Uneasiness everywhere, as I can see from the way people move. I know they’re waiting and trying to stand still while they do, and I come as I come, steady ahead, cut the engine when I should and glide in toward the dock. Kalle stands there with the hawser and his foot in case we start to hit the dock too hard, but mostly I just graze the edge, and so we land. The passengers come out of the cabin, people call out and talk from boat to land, and the world looks very different than it did when we were out in the bay by ourselves and the people ashore didn’t know.

Today, for a change, I am landing at the church dock, because we have the new priest aboard. Which is why they’ve been watching for us a little extra and why they came running as soon as we were spotted in the bay. It’s the verger who kept watch and the organist who saw to it that all the boats people came in were pulled up on the rocks so that we could reach the dock. There is warm smoke rising from the parsonage chimneys, for the women have made fires and have food on the stove. The wind is perfectly calm at this hour of the morning, in coldest May, but oh how glances and thoughts fly through the air. What’s he like? How will it go? But no doubts are visible, for they must receive him heartily and without fear, as if getting used to a new pastor was the easiest thing in the world.

The priest has stood out on deck for quite a while, though his wife has tried several times to pull him in and told him he’ll catch cold. But he stays outside, and when he sees his church climb the hill, signaling to him with its red roof, he grows solemn but wears a broad smile, and when we pull into the cove he looks so happy that everyone decides it will all go well. He waves from a long way out, and they wave back and shout “Welcome!” He shouts “Thank you!” and “Here we are!” and “You good people, you’ve had to get up in the middle of the night to welcome us!”

He has been here once before, so he knows the organist and the verger and Adele Bergman, who is on the vestry and is mightily supportive of the church and the priest. But it’s different now that he is the acting pastor and is going to settle down here with his wife and child. He’s made a good first impression. But when he’s about to step ashore, the boat glides out a bit as if the sea wanted to take him back, and a cold breeze draws across the bay. What that might mean I don’t know.

Adele Bergman knows very well that guests out here are always easy to please. If they’re coming from Åbo, they’ve been traveling for at least twelve hours, not counting the time it took them to get to Åbo in the first place. They’ve been thrown about in all sorts of weather and covered with spray. And when they finally stagger ashore, they have sand in their eyes and cold, damp clothing twined about their bodies. They’re hungry but seasick, shivering but sweaty. They snap at each other and wish they’d never come.

The famous hospitality of The Skerries rests on this foundation. Human beings are so constituted that it takes them only half a day to grow hungry, bored, and tired, so when they finally get a roof over their heads and are presented with a hot stove and warm food, they truly believe they have been snatched from the brink and cannot adequately thank those who have taken them in. Of course the people of The Skerries have been showered with gratitude many times over, but the feeling is always sweet, and they have enjoyed firing up the kitchen range and tiled stove even though it shortened their night.

They stand there looking pleased—Adele Bergman and her Elis, the organist, the verger and the verger’s Signe—for rarely are people so much appreciated for such a relatively modest effort. It is always a pleasure to observe new arrivals, and now, moreover, these five people constitute an official ecclesiastical reception committee with every reason to stand on the dock and inspect the newcomers and take them under their wing and pilot them up to the parsonage.

And guide them into the parish, because it might not be such a bad idea to give the pastor a hint or two about certain tensions within the congregation. This fellow is young, and his wife is even younger, and for the sake of his future success, one can hope that they’re smart enough to learn from others.

The priest is happy. For young people, the trip feels endless because they can’t move and there’s so little to do, and now he’s happy because he’s arrived and can go ashore and shake hands and see to the baggage and shake hands with the mail carrier and thank him for landing at the church dock with all their things. But he’s happy in another way as well, because it’s in his nature, and because there’s a fire burning in his breast, fed by everything he wants to experience and accomplish in his life.

It would be nice to have a Catholic priest who would come by himself and belong more to us alone, Adele Bergman often thinks, in her heart of hearts. In our Lutheran church there has to be a wife and children and furniture tying him down and making demands on his time. People almost think there’s something wrong with a priest who doesn’t have all that, and so the wife gets terrifically friendly looks from everyone as she steps ashore and sets down a child so small it’s a wonder it can stand up on its own two feet. It’s a girl, in a cap and coat slit up the back. “A real little parsonage lassie,” says the organist, who is gallant and loves children and who greets her personally. “Welcome to The Skerries,” he says, and the child does not start to cry but gravely returns his gaze.

The pastor’s wife is small and quick. She doesn’t realize that the boat will stay at the dock until it’s been unloaded but glances angrily at the priest who stands there talking, with the child on his arm, while she scurries about carrying ashore valises and boxes and rolls of bedding and asks what they intend to do about all the furniture lashed to the deck. “Petter, come here!” she finally shouts.

The priest hands the child to Signe, as if he understood how she longs for children. He hurries over to the railing and the others follow. The skipper and Kalle are on their side of the railing, talking, and then, in a flash, they heave ashore the big and the small sideboard and chests and tables and chairs, which now stand newly awakened on the dock.

“Ready to move right in,” says the organist. “Sea view and high ceilings.”

Two beds and a crib follow, then a kitchen table and benches and a dresser and a commode and two bicycles, and finally the household appears to be complete. The pastor’s wife counts and checks while the pastor dandles the child, who squirms in his arms and wants down. Adele looks into the cargo space and wonders how much merchandise the skipper has brought from Åbo for the co-op, the islands’ only store. ”Not so bad,” he assures her. ”Things are starting to get back to normal, bit by bit.” Which in truth they all have a right to expect, a year and a half after the war.

The skipper and Kalle will take the boat over to the co-op dock to unload the merchandise before they can head home, and now they look at the pastor’s wife and wonder if they’ve got everything off. She thinks they have, and the skipper looks to the engine and Kalle loosens the moorings and the priest thanks them once again. The boat starts to leave, but on the dock they all stand around talking, though they ought to go inside where it's warm and get something to eat. As usual, it’s all up to Adele. ”Can’t you all see these people are done in?” she says. ”Now let’s put the most important stuff in the cart and go up to the parsonage.”

They amble through the morning dew up toward the big red parsonage, the air above the chimneys quivering with warm air from the tile stoves where the reception committee has built roaring fires. In the kitchen, there are pots and a teakettle dancing on the stove. The porridge is warm in the pot, and there is bread, buttered and waiting, covered, by the milk pitcher.

Precisely as they should, they stop and catch their breath. ”My goodness, such lovely warmth! And we thought we’d be coming to a cold, damp house and wondered where we’d find the key!” And ”Is it possible? Is this for us? My dear friends, you’re too good!”

”So sit down and help yourselves,” says the reception committee in various voices at practically the same time, taking their own advice and sitting down. Adele has brought cups in a basket, along with enough ersatz coffee for everyone. Bread too, though the idea was that some should be left over for the pastor’s family.

”Oh, oh, oh, so good,” they say. ”What bread! And butter! Look, Sanna, Papa’s putting a pat of butter in your porridge. Now a big spoonful! Wasn’t that good? Now show us how you can drink milk from a cup. And what wonderful coffee! Hot enough to warm my toes. I don’t know how we can ever thank you or pay you back!”

And much, much more. It’s lovely to hear, the kind of reward everyone deserves for a job well done. The reception committee sits and talks, though they know that the newcomers need to get themselves organized and get some rest. Such a long way they’ve come and how nice it is to finally be here and get such a warm, hearty welcome. Here they mean to stay, for they’ll never find a better place.

The priest asks what villages they’re from and wants to know if these are far away. The organist, with whom he’ll have the most interaction, comes from farthest off, but he waves that aside—what does it matter when he has a boat? The pastor has only to call on the telephone and he’ll come. The verger lives close by and has only a narrow channel to row across to get to the church, so he’ll be glad to come and help out. As will Signe, who now thinks she’ll head for the barn and milk the cows.

The pastor’s wife pricks up her ears, for she and Petter have taken over the former priest’s two cows. She brightens with interest and wonders if she can come along but then changes her mind when she stops to think of everything she has to deal with this morning. It will have to be this evening. ”Signe, if you would be so kind as to do the milking today too, then maybe we can go together this evening. From tomorrow on, I’ll take over myself.”

They look at her. Pastors’ wives don’t usually enter the cow barn, but this one says she comes from a farm and has a special interest in animal husbandry. ”So it will be a lot of fun to have my own cows, even though there are only two of them,” she says, and the priest looks at her proudly. ”She’s good at all sorts of things, my Mona,” he says. ”We’ve certainly come to the right place, because we’re going to like all these farm chores, in addition to the church work, I mean.”

He turns again to the organist, who is chairman of the vestry, and smiles and says they’re going to have a lot to discuss. He hopes it won’t intrude too much on his time if he suggests that they get together informally this week and go over the parish routines, and the cantor readily agrees. Adele can see that he likes this priest already, likes him even more than expected. He would have been equally obliging, though somewhat more guarded, toward a priest he liked less, but now he’s looking forward to adopting the new man and supporting him. The way he has done with a number of people who’ve approached him, whether or not it served him well. As he did with Adele, although, to her quiet sorrow, he was already married when she came to The Skerries.

The priest’s wife say she thinks she’ll send Petter to the store this very day, when he’s rested a little, and so he is given directions. He can put his bicycle in the skiff and row across the little inlet, and from there it’s only five kilometers to the store. “It’s nice you’ve got roots in Åland” says Adele. “It’s been a great source of amusement to watch some of the priests from the city try to row a boat.”

Petter laughs heartily and says how fortunate he is to have made friends already with the co-op’s manager, who looks like she might be a friend in need. Adele tells him he’ll be very welcome at the store, and she’ll look forward to his visit. He sits there at the table as if he had all the time in the world, but his wife has grown restless and gets up with her wilting daughter in her arms and looks for a place to put the child down. We ought to get our things into the house, she thinks, and get the essentials in place as quickly as we can.

Adele watches her restrain her irritation at them for not having the good sense to go home, filled as she is to bursting with all the things she wants to do, and she notices quite unexpectedly that she likes the pastor’s wife too, and quite a lot. Because they’re both cut from the same cloth, industrious types called to step in if anything is going to get done. The look at each other and smile. Mona has also taken the measure of Adele Bergman. Adele stands up and says, “All right, my friends, I think we should let the pastor and his wife put their house in order! Thank you so much. And, once again, welcome to the parish. The men can carry up your furniture from the dock, and then we’ll say thank you for today and hope to see you soon again.”

People in the villages like to say that Adele is bossy, but for many it’s a relief that someone takes charge. The organist and the verger and Elis deliver their thank-you’s and head happily for the dock, and Petter runs after them and says for heaven’s sake he can help to carry his own belongings. Four men take care of it all in no time, and soon enough everything is assembled in the parsonage parlor.

Goodbye and thank-you and thanks again. The verger and Signe head off to the cow shed and Adele and the organist and Elis walk down to the church dock, happy as children, true friends of the church. Light at heart, for this has gone well.

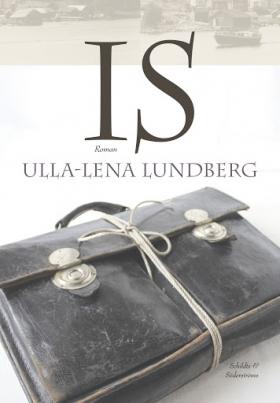

Is

Schildts & Söderströms, 2012

Ice, translated by Thomas Teal. Sort of Books, 2016.

A review of this book appears in this issue.

Ulla-Lena Lundberg is an acclaimed Finland-Swedish novelist and ethnologist. She has published more than twenty works of fiction and non-fiction.

Thomas Teal is an award-winning translator from Swedish.