Ingen ro om natten

(Restless Nights)

by Karl Kofi Ahlqvist

reviewed by Emma Olsson

We meet the narrator in Restless Nights in transit. He takes the train from Copenhagen to Malmö and back again, moving between jobs, relationships, languages and identities.

With a childhood marked by tension between a separated Swedish mother and Ghanaian father, his young adulthood plays out in a chasm. It is a stagnant, lonely place. He’s in his early twenties and has moved from Sweden to Copenhagen, a city of supposed opportunity that would allow him to be closer to his father, who lives across the Sound in Malmö. But it takes more than physical closeness to unite the two men.

In Malmö, our narrator helps his father with his moving business, lifting the couches and cupboards and cardboard boxes of families his father has met through an extensive network of acquaintances, friends and strangers he’s always doing favours for. Busy and working together, his father is at ease. He likes to cook them both dinner and extol the health benefits of spelt flour and moringa powder. But beneath the surface he is absent, unaware and seemingly uninterested in any aspect of his son’s life beyond the occasional weekends he spends with him.

In Copenhagen, the narrator works in a café, frothing milk and collecting dishes; by night, he dates older women for money. Usually middle-aged and always white, his clientele seeks him out for many things – company, sex, even the promise of love – and always for his race and youth.

His appearance becomes his most valuable currency. He tends to it with an attentiveness that might be mistaken for care, were it not so tainted by anxiety.

He learns how to trim his beard to give the illusion of high cheekbones, shaves the hair from his chest, and removes the unwanted ginger strands peeking through his facial hair. He dreads the winter months and their effect on his skin. To his customers, his sexual market value decreases as it lightens. It’s important for him to come across as an African, not a mixed-race guy from Sweden. With frustration and despair he compares himself to the young black men he sees hanging around the red-light district, imagining all the money they must be pocketing from the women who fetishise them. His desperation surrounding his looks recalls an anorexic’s warped reasoning: if only I were thinner, then I’d be happy.

His customers don’t have many redeemable qualities. They’re crass, often judgemental, often failing to pay; some of them seem to think he just dates them for free drinks. They make racist remarks. They criticise him for being too quiet and awkward. Yet they have a barefaced, almost childlike manner of expressing their need for closeness. Our narrator is monumentally lonely, lacking strong family ties or genuine friends, but he never addresses his alienation. Meanwhile, his clients are earnest in the face of their loneliness. They reach out into the void of dating apps and social media for connection. They stay up all night talking to whoever will listen. They bake cinnamon buns and invite a man twenty years their junior over for a chat, never giving up hope that one day they’ll feel close to another human being, that they just have to keep trying.

The narrator lacks this hope. He tries to conjure up a sense of desire for something, but it always feels just out of grasp.

I turned off the water and moisturised my body with Palmolive, started masturbating and tried to fantasise about something, but it was as if all my fantasies had run out and it was impossible to bring them back.

This inability to fantasise goes far beyond the sexual. The narrator is unable to conceptualise what a fulfilling life might look like for himself.

Towards the end of the novel, I started to view the story as a tale of a young man’s depression in the face of an apathetic capitalist system, and I was enraptured by the openness of this depiction. I couldn’t stop thinking about the Lars von Trier film, Nymphomaniac (2013), which follows the life of a woman who identifies as such. Recounting her life story to a priest over several hours, it becomes clear to the viewer that she gets no genuine enjoyment from sex. The pursuit of sex – and with it, the escalating need for arousal and dopamine hits – becomes a symbol of the character’s deep depression.

The narrator in Restless Nights is a sex worker, not a nymphomaniac, but sex holds a similar purpose for him. Dating and sleeping with clients opens up a different space, one separate from the world of his mother and father and peers, where he can place his disappointment about not feeling desired, not belonging, not knowing where to go.

Kofi Ahlqvist crafts an unsentimental world, one where time seems to flatten as characters do what they can to get by. But there is a tired heart beating throughout. Hope is too strong a word for it, but it’s something like that.

Ingen ro om natten

Nirstedt, 2023

176 pages

Foreign rights: Erik Larsson, Albatros Agency

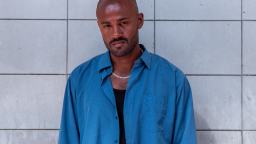

Karl Kofi Ahlqvist is a writer living in Malmö. His debut novel, Ingen ro om natten, won the Katapult Prize for best fiction debut in 2023.