from Tangled Roots

by Maria Turtschaninoff

introduced and translated by Annie Prime

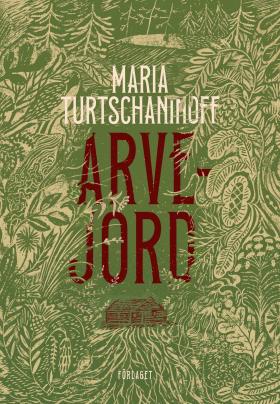

Arvejord (Tangled Roots) is Maria Turtschaninoff’s first work of literary fiction for adults, following several well-loved historical fantasy novels for young adults. An episodic novel spanning over 400 years and nearly 400 pages, it is ostensibly a family history, but perhaps more a story of the land itself.

In the 17th century, a man called Nevabacka builds a smallholding (thereafter named after him) in woodland near a marsh in the Finnish wilderness. It becomes a family home and farm passed down through the generations, and sees both abundance and hardship at different points in history.

We meet characters through a series of intimate, atmospheric portraits that take us deep into their emotional lives and relationships with the land. We witness some grow from childhood to old age, while others appear once and are never mentioned again. Its telling of family history is messy, emotional, sometimes fanciful, in the style of oral tradition, or memory itself. Neighbours, farmhands and step-parents are woven into the lineage. Some stories contain religious experience, myth and magic. Few dates are specified. All the lines are blurred.

Characters in earlier years speak of the forest folk, magical beings that are never fully defined. These mysterious forest-dwellers are feared by some and revered by others. A mood of heathen superstition and reverence for the bounty of the forest is in conflict with Christianity and agricultural progress, which go hand in hand – the desire to dominate the godless wilderness.

On both sides of this conflict, however, devotion to the land is ubiquitous. Nevabacka, its gardens, fields, forest and nearby marshland are the real protagonist. Various characters go into great detail to describe the flora and fauna, the changing seasons, the sunlight through the trees, the scents and sounds. In the final chapters, as modern life takes over, the family lineage thins and Nevabacka falls into disrepair. We are left to mourn the relationship this family – and, by extension, all our families – once had with the land on which they lived, worked and died.

In the end, an urban 21st-century woman inherits Nevabacka and has no idea what to do with it. Maintenance is expensive, and the forest grows ever wilder, poised to reabsorb the farmed land. What does she owe the memory of this place and its people? What do any of us owe our ancestral land?

In this extract, set in the early 18th century, a chaplain has fled his parish after a Cossack invasion. Hiding in the marsh near Nevabacka, he finds he is losing his faith.

Tangled Roots, translated by Annie Prime, will be published by Pushkin Press in April 2025.

from Inherited Land

At night he hears the wolves howling. It is a desolate, lonely sound. He feels a sudden urge to rise from the wolf-skin fur on which he lies as protection from the cold, to put it on, run outside and cry: Brothers! Take me with you!

He resists. He wants to pray, yet cannot remember the words to a single prayer. In wordless torment, his heart turns to God, though he knows that God will not listen to one so far astray. A man of the cloth who has lost his faith.

Finally he falls into a restless sleep, with troubled dreams of running away from the marsh, through the forest, along the fields. Swift as the wind he is, silent and invisible. He runs on all fours, with his brothers and sisters beside him. Their eyes shine yellow in the night. He sees the enemy in the village, but the chapel is still standing. It is no longer his chapel. He runs away from the village, back out towards the marsh, with the winter wind in his nostrils.

When he steps out of the cabin the next morning, he finds a young girl sitting on a rock outside. He cannot see her clearly in the half-light, just her silhouette in the rising mists of the marsh. The mist appears as though full of barely visible forms, gliding along in silence. And she is but one of many such forms, who has happened to sit down for a while.

He stands still for a moment. Wonders whether to address her or wait for her to speak first. From the forest on the other side, he hears the rhythmic pecking of a bird searching a tree trunk for food. The girl looks as though she is listening to the sound. She shakes her head angrily and gets up. Catches sight of him. Curtsies uncertainly, a little bob. Does not speak.

‘Good morning, my child,’ he says. ‘What brings you here at this early hour?’

‘I saw others come here yesterday,’ she says. ‘They asked for your counsel and guidance. Is this something you will grant me?’

‘Yes, my child.’ These words, like yesterday’s, taste bitter. Give counsel? What gives him the right? Wretched lost soul that he is.

‘Even to someone like me?’

Now he understands who she must be. A fallen woman. God has led a fallen woman to my door, he thinks. He is giving me an opportunity to prove that I am worthy, that I can save her soul. The chaplain convinces himself and gazes at the girl as if she were the Holy Mother Herself. And lo, is that not a halo shining around her head? Yes, so it is, shining through the mist! He cannot see her face, but her dress is grey and modest, as befits a woman of her rank. She may have sinned, but she has the right mindset. Humility. He can save her, and in so doing, save himself. He wants to touch the hem of her skirt, to reach out to his saviour, but he controls himself.

‘It is for sinners such as yourself that God sent us His only son. To redeem and save the lowliest, the meekest, the most sinful among us. God loves us all.’ There. He managed to say the words, they did not hurt him; he believes in them. He believes in God’s love.

She appears to ponder what he has said. Something in her posture makes him think that she is not fully satisfied with this. It is not what she wanted to hear.

‘What does this love look like?’ she asks, leaning forward, anticipating his answer. He can see that his response is very important to her. He searches through all the words in his mind, all the sermons he has written, all the advice he has shared as solace and encouragement for his parishioners, fluttering past, all the words, he sees them as though they were butterflies, like flies, leading him all the way back to his seminary days, he hears himself speak vehemently of God’s infinite, merciful love, how each and every person who puts their faith in this love shall come to the Kingdom of Heaven, that they may attain heaven even here on Earth. The words get stuck in his throat, gather there, condense into a lump, air cannot flow freely past them, he cannot breathe, his throat tightens, he is suffocating, he falls to the ground…

The woman drops to her knees at his side. She loosens the clothing around his throat, lays her hand on his head and chants over him, a rhythmical rhyme, rising and falling.

He is on the verge of losing consciousness when he finally manages to gasp for breath. He lies on the ground for a long time and pants for air with his head in her lap. He does not dare look up.

He knows now that this is no fallen woman. No, this is a sorceress. A witch. One who adheres to the old beliefs and follows the old ways. She has no doubt come to the marsh to make sacrifices to the old gods, those who dwell in the forest and marsh and lake. He must protect his immortal soul from her influence, but he has lost the ability to utter the word of God. All his past beliefs suffocate and strangle him. Is he any better than she? No. He remains lying on the ground as wave after wave of shame and despair flood over him.

Eventually, he lifts his head. He would rather not set eyes on the witch and instead sits and stares at the marsh and forest beyond. Presently, she speaks again.

‘They used to love me. Leave offerings for me. They saw me as a mother, a sister. But now…’ her voice breaks. ‘Now I encounter only fear and greed. All the humans want is to force me into submission.’ Her voice is as clear and deep as her sorrow. ‘They defile me and mine. They rob and take, giving nothing in return. So I question this love of which you speak. For I see none of it.’

He is not sure he understands. But he must find a way to respond, if not for her sake, then for his own. He must find new words. The old ones have become shameful and poisonous. If he tries to hold them in his mouth again – those old, outdated, outworn words – they shall kill him.

He realises that he must find the words within himself. Not from scripture. Neither Agricola nor the Bible. They must be his own words. And they must be absolutely true.

‘My wife died from the injuries inflicted upon her when she tried to prevent the enemy from taking our sons away,’ he says slowly. ‘My boys, Mikael and Mattias, were seven and eleven years old. I tried to offer money, but they only chased me away, and I ended up here, in the marsh.’

He takes a deep breath. It is not easy to speak of such darkness and not let it snuff out the tiny flame that burns yet within him. ‘I do not believe that was God’s will. Nor do I believe it was God’s punishment. I know that is what I ought to believe. It is how I am expected to see it. These are the words I have spoken to my congregation when their fathers and mothers, brothers and sisters, sons and daughters have died. When they were chased from their homes and land. This is God’s will, I have said. God is all-powerful. God…’

He looks around. The mists are still gliding gently and secretively across the marsh. A singular bird calls from the forest.

‘God’s love is this. The existence of a marsh. Of a bird. That a forest exists, and morning dawns upon the world. God’s love is that he never withdraws his hand from me, no matter how much I grieve and weep and rage. Whatever I do, whatever happens in my life, there is always the morning, and the marsh, and God.’

The words do not burn or choke him. He sits and gazes across the landscape and slowly begins to feel this love. It flows into him from the marsh, from the morning, it fills his whole being with its warmth. It tells him that he has the strength to bear this too, and that what he needs more than anything is to love the world and love his neighbour, and spread this love as far and wide as he can. Because such is the nature of this love, that the more one shares it, the more one is filled by it.

‘You mean to say that this love can also be found in the forest?’

‘Yes, it exists everywhere,’ says the chaplain. He hears that his voice has changed now. It is steady, full of conviction. ‘Yes. Beneath the forest trees, on the open marshland, on the still surface of the forest lake.’ He chuckles. ‘This is where God is, no matter what name or face one might attribute to Him.’

He knows that he is speaking heresy. It goes against the teachings of the Church. He also knows at once – it dawns as him, as clear as water – that he cannot continue as chaplain. That path is closed to him now, more than a closed door, it is a wall rising all the way up to heaven. He knows that many priests fulfil their role out of convenience, to make a living, but lack faith, and do not care whether what they teach is true or not. He cannot be one of them. He absolutely refuses.

This realisation ought to fill him with deep spiritual distress. Who is he if not a priest? Which path shall he walk, if not that of the Church? Yet he feels no suffering. He draws air into his lungs. He feels free.

For the path to God is yet open to him.

‘Then spread the word to your brothers and sisters.’ She is deadly serious, but the sorrow has left her voice. ‘Tell them this. That there is nothing to fear here. Only love.’

‘I shall. I do not know who will listen, but proclaim this message I shall.’ He is certain that it is true. Until the day he dies, he shall spread this wisdom to whomever he meets. Proclaim this love.

She stands up. He looks up at her face and sees her clearly for the first time. She has a smooth, high forehead, cloudberry-coloured hair and deep green eyes. When he looks into them, it feels like being embraced by the forest, like lying on the marsh on an autumn day and inhaling the scent of cloudberry and wild rosemary, like running barefoot among wood anemones, like a rustling spruce forest on a midwinter night.

Like a dream of running with wolves.

Then, as the sun rises, she turns around and makes her way across the marsh. She walks straight across, where it is wettest and most treacherous, where no human can walk. Without hesitation, without sinking, she walks, and he does not see her reach the forest edge. Suddenly she is simply not there.

For two years the chaplain, who is no longer a chaplain except in appearances, hides in the cabin on the marsh. He performs baptisms and weddings. One person comes to the marsh again and again, without asking anything from him. It is Kristin, and she comes for his sake. Seeing her walk carefully along the dry, safe passage through the marsh fills him with light and joy every time.

He no longer uses those old, outworn, sullied words. He finds new, bright, light ones. Words to convey the truth he has found within. He reads the New Testament, he reads the word of God. He understands them in a new way.

Every day he prays to God, while he ploughs the little field he has dug in the forest, next to the marsh, while he fishes in the pond a short distance away, while he chops his wood and cooks his fish, while he harvests his turnips, and he knows that God has not forsaken him.

When the enemy retreats and it is safe to emerge into the open again, he does so. The first thing he does is visit Skogsperä. Kristin is waiting there. The years have been cruel, but the people at Skogsperä and Nevabacka have not abandoned their homes. Kristin receives him on the steps of the small croft.

‘Kristin,’ he says and takes her hands in his. ‘I can no longer be a priest. If you will have me, I would be yours and share my life with you.’

She squeezes his hands. She will.

He never speaks of the two beings he met out in the wilderness. It is best not to speak of the forest folk much. Let them be and they shall let us be, people say.

Though the man who once was chaplain remembers the feeling of getting lost in those green eyes. In his dreams he walks in their woods, swims in their clear lakes, and runs across the fragrant marshland. And he says nothing more about the wilderness being dangerous or ungodly, or that it ought to be cleared and cultivated.

Arvejord

Förlaget M, 2022, 320 pages.

English edition: Tangled Roots, Pushkin Press, 2025 (translated by Annie Prime).

Foreign rights: Elina Ahlbäck Literary Agency.

Winner of the Swedish YLE Literature Prize 2022.

We are grateful to Pushkin Press and Elina Ahlbäck Literary Agency for permission to publish this translated extract.

Maria Turtschaninoff is a multi-award-winning author known for crafting lyrical, historically inspired fantasy stories starring strong female protagonists. Tangled Roots, her first book for adult readers, was reviewed by Margaret Dahlström in SBR 2023:1.

Annie Prime is an award-winning Swedish literary translator with a passion for magical, mystical tales.