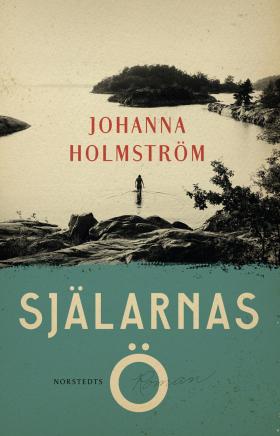

from Island of Souls

by Johanna Holmström

introduced and translated by Fiona Graham

In this ambitious historical novel, spanning more than a century and based on real case histories, Johanna Holmström vividly depicts the lives of three very different women: Kristina, Elli and Sigrid. The link between them is the ‘island of souls’ in the Nagu Archipelago off Åbo/Turku (Finland), the site of an asylum for female psychiatric patients. Kristina is sent there when, abandoned and worn out, she drowns her two young children. Elli, the rebellious daughter of a bourgeois family, arrives forty years later. Sigrid is the nurse who looks after both of them. Johanna Holmström asks us to contemplate the fragility of the line dividing sanity from insanity. The 19th and early 20th-century setting also lends itself to an examination of the gulf between the all-male medical establishment on the one hand, and the lot of female psychiatric patients on the other. The racialist eugenic theories which held sway for much of the period, not least in some Nordic countries, form another strand in the narrative.The State Institute for Racial Biology opened in Uppsala in 1922. Its director, Herman Lundborg, spent much of his time measuring the skulls of inhabitants in northern Sweden, in the deluded belief that this would enable him to prove the inferiority of Sami and Finnishspeaking people. In the excerpt below, Elli awakens after her transfer to the island, and is subjected to a medical examination which clearly shows the influence of ideas about ‘racial biology’.

Extract from Själarnas ö

Chapter 21

EXTRACT FROM PATIENT’S RECORDS:

Name: Ellinor Augusta Curtén

Age:17

Occupation: Student

Height: 1m 62

Weight: 59 kg

Type of illness: Acute psychopathy, dementia praecox, mythomania, nymphomania.

Admission: At parents’ request.

Transferred from Kakola Prison to Lappviken Hospital. Medical certificate issued by Dr Edvin Ahlmqvist, GP.

Registration date: 4.3.1934. The patient spent three months in prison in Kakola, having been given a two-year custodial sentence for repeated thefts, vagrancy, vice, assault, burglary, threats and possession of a cutting weapon. In Kakola the patient heard noises, including birds, which she believed to be in her cell. Violent behaviour with fits and convulsions. Threw objects and ripped her clothes. Yelled out at night and wandered about pulling the bedclothes off her cellmates. Attacked others unexpectedly. Placed in solitary confinement, but no improvement. Afraid of birds she saw and heard in the room. Refused to eat or wash. Slatternly in general; wet herself. Asked for attendants, and claimed to be a celebrity or a gypsy princess, or an orphan. Transferred to Lappviken with no change in symptoms. In Lappviken the patient started to pay attention to her personal hygiene. Dosed with potassium bromide and opiates. Course of Somnifen. Two months in Lappviken. During the patient’s last days there, heavy doses of opiates to sedate her prior to transport. The patient herself agreed to her transfer after a visit from her family’s GP, Dr Ahlmqvist, as the prognosis for recovery in Lappviken seemed unencouraging, and her parents had asked for her to be transferred to a location closer to Pargas.

The foreign substances leave her body stinging and itching, in shivering fits of sweating, blending into the contours of the hours; they are wiped away in the sweat of her brow with a soft, damp sponge. Convulsions, fainting fits: she wakes up on the floor but can no longer recall where she is. Someone puts her to bed, and she flails about with her arms and kicks out around her. The hands are deft and nimble, and she is pinned down with a belt. An enamel cup against her lips and her endless thirst. The thermometer, spat out, crushed against the wall, then inserted in her rectum while she is held down. Worn out from struggling and hoarse from yelling. Nights and days in a tangled bundle of wet, sour-smelling sheets that are soon grey and indistinguishable from each other, one long twilight and glints of light that must be day, until she finally awakes with a sense of physical quietude, and blinks as she looks around her, tired, hungry and sleepy. It’s as if a trapdoor had opened within her and she’d fallen out, tumbling, dizzy, not knowing how or where she’d land, but now the world beyond her half-closed eyes proves to be a bed in a tiny room, and it all comes back to her.

The ferry, the church, the hospital, Sigrid.

She rises from the bed and goes to the door, only to find it locked. She tugs at it, pounds it with the flat of her hand, calls out for the attendants. She demands assistance! She wants to telephone her parents! She wants to speak to her lawyer, who will see to it that she is discharged! She wants to have her injections!

‘There’ll be no medicines here,’ says Sigrid through the door.

But Elli continues to pound it with the flat of her hand and, eventually, with her fists as well. She wants coffee! She wants to read the morning paper! She wants them to – no, she demands that they treat her like a celebrity.

Haven’t they read about her, Elli, in the newspapers? About her and Morris and their crazy flight along the country roads of the whole of south-west Finland, and even as far north as Uleåborg? In that jalopy of his?

They fled until they finally ran out of petrol, and then they fled no longer. At least, she didn’t. But Morris – he fled. He had long legs. A good turn of speed. He didn’t end up lying face down in the mud like her. He bolted like a hare over the last ditch and was gone.

When she gets no reply but silence, the regular meals she refuses to eat, a nurse watching her through the spyhole in the door, whose gaze she rebelliously returns, she finally begins to cry. It is a long, howling burst of crying, and detailed notes are taken. Every rise and fall, every crescendo and decrescendo, every whirling torrent and drawn-out burst of sobbing, and when it ends four days later she lies exhausted on her pallet with tangled hair and soiled clothes, shivering and shuddering with hunger and cold.

On the eighth day Sigrid unlocks Elli’s door. The chamber pot is overflowing and she rises swiftly when the nurse enters the room. Strokes her hair, smoothes her clothes. She, who’d been so well turned-out when she arrived.

Sigrid smiles, but Elli’s gaze slips away; she refuses to look at the nurse standing in front of her. The sun filters in through the window, filling the silence with dust that dances in slow eddies in the broad shafts of daylight. Elli hasn’t even noticed that the long, wet days have given way to dazzling sun, but now she blinks in the sharp light with tired, stinging eyes. When did she last sleep?

Well, when …

When Elli finally meets Sigrid’s gaze from under half-shut eyelids, Sigrid has to repress a sigh. The girl before her is a child. A woman with a child’s demeanour and a child’s way of thinking. They joked about her while she lay in her room calling for coffee and zwieback biscuits. Little Miss Hollywood, they called her. And yes, they’d read about her in the newspapers. Her transfer from Lappviken had attracted a good deal of attention. She’d been photographed in handcuffs on her way out through the hospital entrance. On that occasion she’d given the photographers a wry smile and a dark look from under the brim of her hat. She’d been permitted to wear her own clothes. She’d been allowed quite a few privileges.

Well, thinks Sigrid, she’ll be brought down a peg or two soon enough.

Her own clothes have been taken away from her, and she’s been calling to have them returned for several days now, but Sigrid has continued to refuse.

‘Then I’d rather walk around with nothing on!’ Elli yelled in reply to a question about clothes, and Sigrid, who had held out the hospital uniform to her, inclined her head and said:

‘As you wish. It can get cold here in winter. Here it’s only animals that wear fur to keep themselves warm.’

Elli wound her arms about her and stared after Sigrid when she’d gone.

‘I’m not staying here that long! You’ll have to get through the winter without me – I’ll be gone long before that!’ she cried.

Now they look into each other’s eyes. The dull gleam of Elli’s green eyes meets Sigrid’s pale blue gaze. The hard line around her mouth has softened somewhat, but it’s still there.

‘I … I want to see my lawyer. Mr Lucas Lindgren. He’ll see to it that I’m discharged,’ she says, and her voice is thick and hoarse from all the hours of weeping, her throat sore from all the shouting.

Sigrid nods towards the door, which stands open.

‘The doctor wants to see you now – if you feel ready.’

Elli stands there in a quandary. She fingers her skirts with their yellow urine stains. The stench in the room is as foul as that of an animal’s cage.

‘I want to … Can I smarten myself up first?’

‘You won’t have time. The doctor has a lot of other patients to see. But you can get changed in his surgery. Your hospital clothes are clean. We’ll set out a basin for you so you can wash off the worst of it. Later, after you’ve seen the doctor, we can think about a bath.’

They undressed her in prison, in Lappviken, and now here as well. Always this undressing. Always this penetrating scrutiny of bodies in various stages of decay. Always this taking of notes on the shape, colour and condition of such bodies. The search for the defect, for malformations, scars, anything that might provide a physiological explanation for why their lives have gone the way they have. The clues lie in the length of their limbs and the shape of their skulls. In the genography of their bodies. In their ugly facial hair or their joined-up eyebrows. In their foreheads – too high, too low, or too average. In the smell of their fear.

Now she stands naked before the doctor. Slowly, and with downcast eyes, she has removed her garments one by one. Embarrassment has made her movements slow and reluctant, but there is also the relief of being able to take off clothes that are stiff with dirt. She has felt his eyes on her while undoing buttons and unhooking eyes, pulling off her stockings, letting her drawers fall to her ankles. Her skin contracts into goose pimples. She feels her breathing expand her ribcage, sending oxygen all the way to her fingertips and scalp. She smells the odour of her body, of her vulva. The dense, sour stink of sweat and urine rises from her crotch.

She thinks: Morris, where are you now? and switches off her feelings, to avoid breaking down.

Seated at his desk, Doctor Mikander watches her. Legs crossed, the long, white coat like armour covering his body, stiff, clean, impeccable. His dark hair is combed to one side. It glistens with pomade. He has the same kind of round spectacles as her father. The same kind of pomade as Mr Ekman, the managing director at the scissors factory.

He gets to his feet: standing before her, he raises his hands to her head, slips his fingers into her hair, then deftly examines the shape of her skull. Sigrid makes a note about the thickness of her hair, and Doctor Mikander pulls it between his finger tips to feel its texture. Dry, auburn in colour and unusually frizzy. He asks Sigrid for the craniometer and Elli starts when he opens the instrument, which resembles a large, sharp set of callipers, fearing that he may be about to poke it into her head somehow. Sigrid rushes forward and places her hands on Elli’s shoulders to calm her, but Elli can sense the tension in the nurse’s fingers. She is ready to be firm if necessary, and her touch is as much a warning as it is protective. The measuring instrument opens, and Doctor Mikander mumbles the measurements, which Sigrid, shuffling over to her papers, notes down. Then he continues the examination. Elli has to follow his index finger with her gaze to test the mobility of her eyes. Meticulously, he scrutinises the colour of the iris, the size of the pupil and the thickness of her eyelashes. Her eyebrows, he notes, are luxuriant, almost bushy, and rather close-set.

‘Unusually dark hair above the upper lip, otherwise normal facial hair. Open your mouth and stick out your tongue,’ murmurs Doctor Mikander. ‘This is all normal. Small tongue; moist, as normal; colour, normal; throat clear of any infection, a healthy red colour. Abraded chewing surfaces, but teeth normal in other respects. Close your mouth!’

She swallows, and his hands roam further, slide down over her throat and the sinews of her neck, check the mobility of her head and the stiffness of her shoulders.

‘Tense musculature in the nape of the neck and the shoulders.’

He grips one of her hands, examining the shape and colour of her nails and the soft texture of her hands.

‘Up!’ he says, and she stands perplexed for a moment until he tugs impatiently at her arm. ‘Up!’

Doubtfully, she raises one arm.

‘Both arms!’ he says, and she does as he says, stretching her arms up towards the ceiling.

‘Thick hair!’ he bursts out, and brings his nose closer to sniff at her armpit. ‘Rank body odour.’

Swiftly she lowers her arms, stung by his comment, and Doctor Mikander, startled, steps back to avoid being poked in the forehead by her elbow. He blinks rapidly, as if he’s lost his thread, then he looks at her for a moment before he says:

‘Shall we?’

Again, hands cupping her breasts, massaging and kneading them thoroughly and at length, pinching her nipples and lifting up her breasts, then letting go, repeating the procedure several times.

‘Heavy … large … full but soft … perhaps slightly lumpy. Firm, not pendulous. Large, dark nipples.’

Elli can’t be sure, but she thinks he sounds satisfied when he comments on her breasts. As if he were praising them – and that embarrasses her. More than anything, she would like to squat down and cover her body with her arms, but she remains standing as if turned to stone, passive and apathetic, while the examination continues. Doctor Mikander asks Sigrid for a measuring tape, then measures her bust, waist and hips. He measures the length of her arms, legs, torso; the circumference of her head. She starts to feel cold, but clamps her teeth together to stop them chattering.

‘Body hair … thick, dark. Pliant skin. Legs disproportionately long in relation to the torso, heavy thighs, some tendency to put on weight, short and thick-set … East Baltic characteristics, Finnish mother, isn’t that right? Yes, typically Finnish build.’

He goes to the wash basin and washes his hands. Sigrid brings a towel and dries them. Then he approaches her, glances at the examination table, which has filled her with terror ever since she entered the room, and nods towards it.

‘Get up onto the table and lie on your back.’

She stays where she is, swaying indecisively. Lifts her hands and shields her upper body with her arms. Shakes her head almost imperceptibly. Sigrid makes a movement, leans over and takes a half-step towards her. Elli looks from her to Doctor Mikander. Top dog, underdog: there’s nothing for it but to obey.

‘Come on!’ raps out Doctor Mikander, and Elli stumbles over to the table.

The cold, sterile instruments on the tray next to the examination table clatter, and Sigrid has to hold Elli’s legs when she instinctively clamps them shut. She screws up her face and turns it to the wall when the hard pincers are thrust into her and lever her open. She tenses her body until she is shaking, clenches and spasms, and the doctor sighs and dilates her slightly more, until she cannot repress a miserable whimpering sound. She thinks she is about to split open, and he says nothing to calm her. He mutters, almost to himself, and Sigrid takes notes. External sexual organs: abnormal. Very fleshy labia, overdeveloped clitoris. Elli’s eyelids flutter and she feels tears trickling out of the corners of her eyes. What does that mean, that her clitoris is overdeveloped? What is a clitoris? Who can she ask? But Doctor Mikander carries on muttering. Excessive sexual drive. The male sexual organs are dominant. Not hermaphroditis.

‘Is your menstruation regular?’ he asks, and she blinks and blinks until she manages to murmur: ‘Sometimes.’

Sigrid notes when it first started, how long it continues each time, whether there is much blood, whether she suffers pain, how she feels before, during and after her period, the colour and consistency of the blood: all this is extremely important to be able to establish her general condition and future treatment.

Afterwards, when the hard instruments have been extracted from her body, leaving behind a limp, warm emptiness of the kind that follows physical violation, she rolls off the examination table and pads over to the chair where the light blue uniform has been left folded up. She crawls into it like a fox slinking into the protection of its lair, and once she has buttoned it up and is sitting with the soft fabric next to her body and the shadow of his touch lingering like a grimy imprint on her skin, she finally manages to open her mouth and ask the question she has wanted to ask ever since she set foot on the slippery, salt-besprinkled landing-stage opposite the church.

‘Doctor. Tell me. When will I be leaving? When can I go home?’

Her voice is hoarse and she clears her throat, and he looks at her for a while from behind the round spectacles before he answers.

‘Have you understood your diagnosis, Miss Curtén?’

She shakes her head.

‘Dementia praecox. Premature dementia. A serious case of psychopathy. Hypersexuality … The condition from which you suffer, Miss Curtén, has no known cure.’

Elli gives him a confused look and shakes her head again.

‘I don’t understand. If there’s no cure … then what am I doing here?’

Doctor Mikander toys with his fountain pen while he reflects. Then he leans forward over the table.

‘Most of the patients have been here on the island for years. Their symptoms haven’t changed, nor will they. This is an institution for the chronically ill. Very, very few patients are ever discharged from this hospital. Virtually none, in fact.’

He sighs before continuing.

‘There is no cure. Only care.’

Elli looks at him wordlessly. Doctor Mikander’s words descend upon her like a net, and it takes a while before she can speak again.

‘My parents … my mother and father! They’ll come and take me home! They won’t let you keep me here!’

Doctor Mikander presses his fingertips against each other, and his hands rock back and forth a few times towards the table top. Then, suddenly, he leans back in the chair and crosses his legs again.

‘Miss Curtén … I’m not keeping you here. It is your parents who have had you admitted to this institution. And that is just as well. You are ill, Miss Curtén! And the worst of it is that you don’t appear to recognise that yourself. How can you ever get better if you don’t even grasp that you are ill?’

‘Get better?’ Elli bursts out, dismayed. ‘But didn’t you say just a second ago that I’ve been diagnosed as incurable?’

They stare at one another in silence. Elli draws a deep breath.

‘Do you really think .... my mother and father will agree to me being here for several years? Maybe my whole life? That they’ll accept your talk of incurability?’ she asks then, and Doctor Mikander removes his spectacles and rubs the bridge of his nose.

‘They only want to give you the best care you can be given,’ he replies.

‘So there’s no chance? Is that what you’re saying? No chance of being discharged?’

‘Well. That depends. The thing about women’s nature, you see, is that it’s cyclical. The same is true of insanity in women. The link between these cycles of insanity and menstruation is generally clear, and when menstruation ends, so does insanity in very many cases. Many patients have thus been fortunate enough to be discharged at that stage,’ he explains.

Elli looks at him without saying a word.

Many women are discharged when their menstruation ends. When is that?

She sees herself as a bowed, bent woman blinking in the sunlight as she wanders down the path towards the landing-stage where she once came ashore, light on her feet and with life pulsing wild and untamed against her ribcage.

No, she thinks then. No. Mother won’t let that happen. I won’t stay here for good!

Själarnas ö

Förlaget (Finland) and Norstedts (Sweden), 2017

Rights: Federico Ambrosini, Salomonsson Agency

We are grateful to Salomonsson Agency for permission to publish this translated extract from Själarnas ö.

A review of Själarnas ö by Emma Naismith appeared in SBR 2018:1 and by Fiona Graham in the European Literature Network.

Johanna Holmström’s first novel Asfaltänglar (Asphalt Angels) was reviewed by B.J. Epstein in SBR 2013:S.

Fiona Graham is a translator and editor working from Swedish, Dutch, German and other languages.