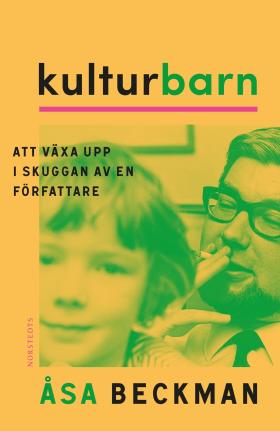

Kulturbarn: Att växa upp i skuggan av en författare

(Culture Child: Growing Up in the Shadow of an Author)

by Åsa Beckman

reviewed by Kathy Saranpa

Because authors can attain somewhat mythic proportions in the public mind, it’s easy to forget that they often have families – until one of their children writes a tell-all. One such child, Åsa Beckman — whose father Erik Beckman was a prize-winning poet, novelist, dramatist and literary critic — has written a study broader than a true confession. She examines the family dynamics of several Swedish authors, with Thomas Mann’s ‘clan’ adding an international comparison, and talks about the damage done to the children of writers in particular.

Beckman divides her book into several shorter chapters, each focusing on one aspect of the similarities she has found while researching adult children of authors. She intersperses these chapters with more personal anecdotes from her own life. While the reader can detect the pain and anger Beckman experienced as a result of her father’s treatment, she does not lack in empathy for his situation, and by extension the situations of other authors.

According to Beckman, the typical writer has a family surrounding him (most of the writers she explores are male) that becomes a kind of symbiotic unit, or even a family business of sorts, in which the mother and the children tend to the author’s needs. He must be happy and undisturbed in order to work well, and it is only through his work that the rest of the family will be sustained – so they have every reason to maintain this dynamic.

What’s forgotten in this equation is that children are developing individuals, not worker bees. When all attention is focused on the ‘genius’ or ‘magician’ (Beckman also explores the terms often applied to successful, well-known writers), the needs of children often go ignored. One of the main issues that seems to surface in adult children of writers is a lack of identity – the child becomes part of a kind of ‘corporation’ but not a discrete individual, with their own aspirations, temperament and preferences. This makes it difficult for them to perceive and pursue an independent path in life.

Beckman cites a depressing series of traumas reported by adult children of authors either in books, letters or interviews. Otto Gabrielsson’s story may be the most heart-wrenching. His father, Finnish writer and cultural figure Jörn Donner, refused to give him a free copy of his book, telling the young man to go buy his own copy. Not all of the traumas are as dramatic or visible; often the damage takes the shape of a lack of self-confidence (which Beckman herself has experienced in her career as a writer) or an unhealthy adult attachment to the famous parent..

Female authors with unhealthily symbiotic families seem to be a rarer occurrence, and Beckman presents her ideas about why that is, but the women can do as much damage as their male counterparts. Particularly shocking is the case of Felicia Feldt, daughter of Anna Wahlgren, who disclosed being molested as a child in her bohemian family home, unprotected by a mother who had cast herself as a kind of child-rearing expert. When Feldt’s book appeared, her mother accused her of trying to murder her and her reputation by writing something so disgusting.

For the children of writers, there are positive experiences as well. There is the feeling of being part of something ‘amazing,’ as the Mann children expressed it, or even a sense of ‘we’ (our remarkable family) vs. ‘them’ (the less remarkable public). Beckman talks about meeting Swedish cultural figures as a child and the sense that their family was on a higher plane than normal humans. An author’s magic dust settles on his (or her) children as well as on the pages of the books they create. But this feeling can also strengthen the sense of inadequacy when these children attempt to write something of their own as adults and put the brakes on their creativity. Beckman claims that she would have been more productive had she not constantly second-guessed her father’s reactions to what she was writing.

This book is thoughtful, provoking, and saddening by turns. Beckman’s concluding section takes a look at a possibly brighter future: writers on their laptops in the living room instead of in an imposing and intimidating office that the children may not enter, popping on a head set to concentrate with the children all around them. Maybe the next generation of authors’ children will grow up in the sunshine rather than in the shadows of their writing parents.

Kulturbarn: Att växa upp i skuggan av en författare

Norstedts, 2024

250 pages

Foreign Rights: Linda Altrov Berg, Norstedts Agency

Åsa Beckman is deputy director of culture and literary critic at national newspaper Dagens Nyheter. She regularly writes columns in the newspaper and has previously published collections of essays and columns.