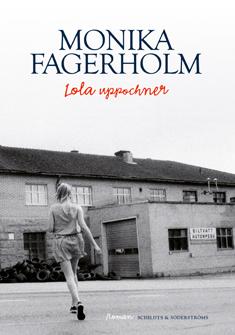

from Lola Upside-Down

by Monika Fagerholm

translated by Anna Holmwood

On the surface, Monika Fagerholm's new novel seems to be a classic thriller in a contained setting, as a group of people return to a place where a crime was committed seventeen years earlier. But it is also a darkly humorous evocation of the sluggish and suspicious dynamic of small-town life.

As ever, Fagerholm's innovative language is a focal point. To quote one reviewer of the novel: 'the language is breathless and choppy, like a teenage girl running away from something in the woods'.

from Lola uppochner

Saturday the third of September 1994, six thirty in the morning. Jana Marton likes to row. She also likes to get up early in the mornings. Especially when staying at the summer house, where she is now, with Dan-Johan. The house is small, a cottage. A living room with a kitchenette, two bedrooms, a terrace with a view over the lake and a sauna accessed from outside. Quiet, empty. The door to Dan-Johan’s room is closed. Dan-Johan is sleeping; it’s the weekend so he has time off. Jana Marton is going to work. She works evenings and weekends during termtime as a shop assistant at Gusse Marin’s supermarket in Flatnäs, mostly on the till. She’ll be riding her bike there soon. Takes less than half an hour; only seven or eight kilometres from the cottage along the lake up to the edge of town where the supermarket stands at the beginning of the main road into the centre, between the barracks and the mental hospital and opposite the new cemetery.

The lake is still, the air is clear. One of the first mornings to have that autumn crispness; the sky is high and blue and sharp in the morning light. Like a beginning, or the suggestion of an ending.

Jana Marton goes to the wooden jetty and pushes out the rowing boat that had been dragged up onto the lake’s shingle beach. The red fibreglass boat is light and flimsy, and the oars like to slip out of their white cradles. But Jana Marton knows how to handle it – she’s rowed the same route every morning she’s been up at the cottage this summer, which has been most days. Round the small islet in the middle of the lake and back again. Quick, powerful pulls of the oars. A workout. Jana Martson is sporty, a middle-distance runner, she trains regularly with the local sports club. 800 and 1500 metres are her distances and last autumn she came third in the district championships. But all that winning and losing doesn’t mean much to her. And neither does she show as much promise as Rigmor Tiedmans or Filip Martin who are also members of the club, though he hasn’t been training there much recently. Nor has Fanny Holmström, who died, wasted away from anorexia: pictures of Fanny Holmström on the walls of the changing room and in the coach’s office, Fanny on the podium, Fanny, sinewy and gaunt, about to cross the finishing line, full of herself, with a slight smile spread across her lips.

She likes running, Jana Marton. Short distances, long distances, in the forest or round and round the track. Just as she likes to swim and row.

The creaking of the oars in their cradles, an owl hooting somewhere; breaking the vast silence filled only by echoes of the tiniest sounds. Drip, drip. Drops of water fall from the oars as Jana Marton pulls faster, forwards, on and on. This loneliness. The way she blasts herself out in the clean landscape, so still, crackling with green and morning. From the lake the shores look uninhabited, with just a few lone wooden jetties jutting out into the reeds between medium-sized rocks. But there are houses beyond the trees and bushes. Not many, but still. Summer places, built on land owned by the local cooperative bank which in turn bought it from Birger Stenqvist – a smallscale tycoon, who Jana Marton knows in his capacity as the chairman of the sports club.

You are now entering the human heart. A voice suddenly appears in her head in time with the oars, Anita’s voice, a whispering persistence, but not irritating. She hears it sometimes, pounding in her head like rhythm. Anita, the Mill, in the room with the jigsaw puzzle that is never completed, books, their spines with the strange phrases that Anita reads out loud... You are now entering, entering...

‘Jana, you are now entering the human heart. Does it look like this in there?’

She is nearly round the islet, a nameless lump of rock covered in trees, far too small and stony to be built on. Dan-Johan calls it and the spattering of rocks that surround it ‘the lava-landscape’ as he sits on the terrace with a pair of binoculars, relaxing after his sauna on long, light summer evenings. Like yesterday. Dark, sharp rocks, ghostly from a distance and especially when viewed through a pair of binoculars.

Something blue and shiny among the stones. Strange. Maybe that’s why it catches her eye. She pulls in, draws closer. A plastic dinghy, used to board a larger yacht, but there aren’t any on this lake as it’s full of reeds and doesn’t connect to the sea. Blanksjön isn’t a coastal bay created by sinking water levels, but a proper freshwater lake and Dan-Johan says that it was once so clean you could drink from it.

The dinghy is stuck in the reeds between the stones, as if adrift, a scraping from the hull. ‘Sea Adventurer II’ in big, gold letters painted on a mahogany sign attached to the stern.

Close up, she peers in, carefully.

The boat is empty. Half-filled with water, wedged against a stone under the water’s surface, weighed down by the water inside and tilted to one side. No oars, no wooden slats. A dark rag floats in the water, some rubbish in the bottom, coins, otherwise nothing. She bends and fishes up the rag: a sock. Drops it back, turns quickly, and rows back out and towards land as fast as she can.

Drags the boat up and runs to the cottage and washes in the sauna with the warm water left on the stove from last night. Rinses away a feeling, a dull ache of – strangeness. She wants to tell Dan-Johan about the boat but it’s still quiet inside so she’ll have to wait for evening when she gets back from work. Dresses, jumps on her bike, is on her way.

Later Jana Marton will come to understand, deep down and irrationally but again and again, wilfully: that the silence, that the boat, you are now entering... that they were all signs. She needs protection.

The dirt track runs a kilometre from the cottage before it reaches the tarmac road. A forest road that twists unevenly but is otherwise well maintained because it is gravelled every autumn. Maintained by a road association in which Dan-Johan is chairman and the driving force, the one who sees to it that there is no cheating when improvements are made despite the considerable costs. He is careful about that sort of stuff, keeping the roads serviceable all year round. This has at times caused arguments with the neighbours as it can be expensive and because Dan-Johan’s cottage is closest to the road so he pays the least. There aren’t many of them, four cottages plus Rouhe’s long tentacles which have reached into the forest. A clubhouse now, but it used to be a small hunting cabin. Rouhe is a ‘gangster’ of sorts, has his ‘men’, or at least he tries. Tries. That’s how Dan-Johan phrases it. For some reason he thinks it funny rather than scary to have these idiots driving their old bangers around in the middle of the night.

‘Are you scared of them?’ Anita at the Mill asked once, because she likes to ask those sorts of questions, to elicit fear even when it doesn’t exist.

‘Scared?’ came Jana Marton’s response, along with a shrug of the shoulders. She’d never thought about it.

Anita pressed on, determined to get to what it was she was really trying to say. ‘Just say your name and that you know me, that we’re friends. Best friends brought together by the befriending service. The third sector at work. Praise the Red Cross, hallelujah.’

‘I’ve told you a thousand times I’m not here via the befriending service,’ Jana Marton tried to persuade her but rather than listen, Anita continued to harp on about it and so Jana Marton has barely been to the Mill all summer. You can’t talk to Anita, she only hears what she wants to hear and the rest she makes up.

But back to the road. Dan-Johan does say that Rouhe has never been late with his payments, unlike some of the ‘engineers’ as Dan-Johan likes to call some of the neighbours along the road.

But Dan-Johan isn’t a difficult person. He seeks out solutions. He likes dealing with people and listens willingly to their arguments. And it’s important to have a good relationship with your neighbours, so he has on occasion paid more than he should – ‘the main thing is that it gets done’. The only time Dan-Johan has ever got into a conflict that couldn’t be resolved was when he left his hunting circle last year; there are some who still have it in for him about that. He did it for Petra’s sake, it was a condition for her and Jana moving to his place in Flatnäs; she was very upset: ‘You have to stop killing innocent animals!’

About halfway up the dirt track Jana Marton spots something on the road. A shoe. Brown. A man’s shoe. With a leather lace woven along the side, a sailing shoe. Which is how she ends up at the sand pit a little way down a side road.

Throws the bicycle down by the shoe, wheel spinning in the air, and runs. Doesn’t stop until she’s there. At the pit. Dark walls of sand rise around her. She nearly stumbles over him, lying there.

On his stomach, his head turned to one side. A blue sock on one foot and on the other – the other shoe.

Bare-chested, but brown with blood.

And more blood. His eyes are open.

No.

She doesn’t know Flemming Pettersson, but she recognises him. And there he is, still and lifeless.

Something changes irrevocably. An owl hoots somewhere. Otherwise silence. She doesn’t scream.

Lola uppochner

Schildts & Söderströms, 2012

Foreign rights: Layla Belle Drake, Salomonsson Agency

The Salomonsson Agency kindly gave permission for publication of this translated extract.

A review appears in this issue.

Anna Holmwood works as a literary translator from Swedish and Chinese, and as a literary agent.