Beyond Moomin Valley: Tove Jansson's Writing for Adults

by Claire Dickenson

2014 marks the centenary of the birth of a much-loved writer whose breadth of output deserves to be wider known.

Tove Jansson is arguably one of Finland’s best known exports and one of the country’s most widely read authors. Despite the fact the majority of her works were originally published in the middle of the twentieth century, they are still hugely popular today, not only amongst Finland’s Finnish and Swedish-speaking populations, but around the world. The works for which she is undoubtedly best known are her books following the adventures of the Moomins, which have to date been translated into 43 different languages, including Faroese, Thai, Georgian and Welsh. There is, however, far more to Tove Jansson than Moomins: she was also an accomplished artist and penned a number of books for adults.

Jansson’s books for adults are a combination of short-story collections and novels, written during the latter part of her career; the first being published when she was 54. Whilst the death of her mother, illustrator Signe Hammarsten (also known as Ham) was, by Jansson’s own admission, a turning point in her life and career, her books had already begun taking a darker and more adult path, years earlier. Despite the popularity of her earlier works, her books for adults, published primarily post-1970, are still relatively unknown.

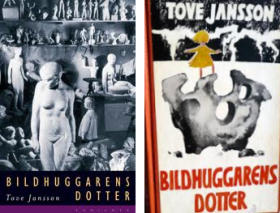

The first of these books is Bildhuggarens dotter (The Sculptor’s Daughter; 1969), an autobiographical account of Tove Jansson’s early childhood. She chose to narrate her early life in a series of short stories, each telling a tale from her childhood in the interwar years, split between Helsinki’s Katajanokka district and the Pellinki archipelago near the southern town of Borgå (Porvoo). The stories are told through the eyes of a child, which, combined with Jansson’s unique perspective on the world and everything in it, and ability to make even the most mundane of things enchanting, provides a magical account of her childhood. Whilst the book is primarily autobiographical, there are certainly places where the truth has been stretched, contorted or discarded altogether, drawing the reader further into Jansson’s world. Bildhuggarens dotter also provides an insight into the key role art played in her life, growing up with two artist parents; she would later state in an interview that her writing and the Moomins were secondary to her painting.

Lyssnerskan (The Listener) was the first of Jansson’s books to be published after the death of her mother, the point at which she declared the Moomin series over. As with Bildhuggarens dotter it comprises multiple shorter stories; however it does not follow the same characters throughout: rather each story is unconnected to its predecessor and successor. Lyssnerskan contains both newer stories and those written earlier in her career, and each offers a glimpse into a small fragment of the protagonists’ lives. In the title story, the reader meets Aunt Gerda, an elderly woman who has begun to forget – names, people, family – and who reacts to this by shutting out the outside world and devoting herself to creating a map of all the people she knows and the relationships between them. Not content with this, however, each day she changes the map, creating and destroying relationships with a few strokes of her pen.

It would be another seven years before Tove Jansson would release her next collection of short stories – Dockskåpet och andra berättelser (The Doll’s House And Other Stories, published in English as Art in Nature; 2012). As in Lyssnerskan, the stories are fragments, often with no clear beginning, middle or end, throwing the reader into the story and allowing the relevant details to fill themselves in along the way. Whilst it does not claim to be autobiographical, many aspects have clearly been inspired by Tove Jansson’s life. The sculptor in ‘Apan’ (The Monkey) has hints of her father; author Ellinor in ‘White Lady’ bears more than a passing resemblance to Jansson, who never had children herself, as she muses over how she spends her days writing for children, yet does not really know them at all. It is not hard to imagine that ‘Den stora resan’ (The Great Journey) was perhaps most clearly inspired by Jansson’s personal life and very close relationships with partner Tuulikki (Pietilä, an acclaimed illustrator) and her mother, telling the story of Rosa, who tries to balance her relationship with partner Elena with her incredibly close bond with her mother.

Resa med lätt baggage (Travelling Light; 2010) is a collection loosely based on the theme of journeys, usually resulting in the protagonist being thrown into bizarre and often awkward situations. ‘Främmande stad’ (A Foreign City) follows the adventure of an elderly traveller who realises has forgotten where he is staying on a trip abroad, whilst ‘Kvinnan som lånade minnen’ (The Woman Who Borrowed Memories) sees Stella return to the apartment she has been renting to friend Vanda for 15 years, only to find that Vanda has claimed her possessions, memories and life as her own. As always, Jansson manages to make the oddest of stories believable and captivating with the deceptively simple imaginative tone for which she has become known.

Rent spel (Fair Play; 2007 – translation by Thomas Teal and winner of the 2009 Bernard Shaw Prize for Swedish Translation) is in many ways a continuation of the theme begun in Bildhuggarens dotter, following the lives of an artist and an author in Helsinki, the archipelago and elsewhere. Whilst there is artistic licence aplenty, the similarities between this love story and Jansson’s life are more than coincidental. The short stories in this collection all follow Jonna and Mari but are otherwise unconnected.

The short-story genre is clearly one Jansson felt comfortable in, embracing its flexibility in Brev från Klara (Letters from Klara). Whilst classed as a short-story collection, as the title suggests, it includes several pieces written in the form of epistolary stories, whilst others are diary entries, all following typically Janssonesque characters and the strange situations in which they find themselves.

Tove Jansson’s last book, Meddelande (Message, published in English as A Winter Book; 2006) features some of the stories originally released in Bildhuggarens dotter, alongside some newer works, with tales focusing on everything from childhood to ageing, to the relationship between people and the nature in which they live. Meddelande combines Jansson’s rich imagination with real-life inspiration, and ends with some sobering reflections on the ever-increasing limitations that come with growing old.

Tove Jansson’s first full length novel for adults, Sommarboken (The Summer Book; translated by Thomas Teal, 2003, first published in English in 1975) was released in 1972 and is set on an island, following the summertime adventures of two of the island’s inhabitants: six year old Sophia and her grandmother. Sophia and Grandmother use their imaginations to create all manner of fantastic adventures in magical worlds across the tiny island, and it is only on reflection that the reader notices the dearth of concrete events. The age gap of fifty or more years between the two appears to be of minimal importance and the book is full of witty and insightful remarks of the kind that will be familiar to anyone who has read any of Jansson’s other works.

Just two years after Sommarboken, came Solstaden (Sun City; 1976). Inspired by Jansson’s travels in the USA, it explores the parallel world occupied by the elderly residents of a retirement home in an area commonly known as God’s waiting room. Expanding on a theme touched upon in some of her other books, Solstaden sees Jansson ponder various aspects of growing old, from the humorous to the darker and more thought provoking, and it is this darker side that Den ärliga bedragaren (The True Deceiver; 2009) explores more deeply. Perhaps Jansson’s most unsettling book, it witnesses the coming together of brutally honest Katri and Anna, who lives in a world of floral bunnies. It delves into the idea of truth and questions the value of honesty above all else, with a psychological element that makes for uncomfortable but compelling reading.

In Stenåkern (The Field of Stones) recently retired journalist Jonas leaves the city to spend the summer in the country with his two daughters. Tasked with writing the biography of the unpleasant ‘Y’, he soon finds it morphing into the story of his own damaged family life. A shorter book, Stenåkern has a humour that makes it easy to read from cover to cover in just a few hours, despite the dark content. Jansson’s final collection, Anteckningar från en ö (Notes from an Island), released in 1996, is more positive in tone, comprising entries written by Jansson, her mother, and local builder and friend Sven Brunström. With illustrations by Tuulikki Pietilä, the book covers all aspects of their time on the island of Klovharun, from sailing to fishing to communicating with the outside world. Also covered is the eventual decision to give up their summers on the island, as ever showing Jansson’s willingness to discuss the more difficult aspects of life. Whilst Anteckningar från en ö, and two others (Stenåkern and Brev från Klara) have yet to be published in English, a good number of Jansson’s adult works are currently available, and make for thought-provoking reading, regardless of whether one is a Moomin fan or not.

A number of Tove Jansson's books for adults have been translated into English and published by Sort of Books.

Claire Dickenson completed an internship at FILI and studied translation at University College London.