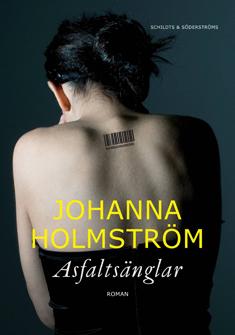

from Asphalt Angels

by Johanna Holmström

introduced and translated by Nichola Smalley

Johanna Holmström is a Finland-Swedish writer based in Helsinki, Finland. She has written several prize-winning collections of short stories and two novels.

Asfaltsänglar is her second novel, and follows the lives of two sisters, Samira and Leila. Both are navigating the complexities of being young, female and Muslim in Finland, and the extract below shows the erratic path that this navigation takes for Samira and her friends.

from Asphalt Angels

When they were teenagers they’d been masters at stealing time for themselves. Samira’s dad Farid didn’t keep tabs on her movements. He let her go wherever she wanted. What else could he do, when he set such a bad example himself? But in the evening, she had to be home by ten o’clock at the latest. It was her mum Sarah who had the key. Sarah, who sometimes decided that Samira had been running around long enough and locked the door to the house with the deadlock, hanging the key around her neck.

So Samira, Jasmina and their friends Masha and Fayrooz were forced to use all their cunning to dupe their parents, when the old tricks, like staying over at each other’s houses, had stopped working. They booked courses in flower arranging; courses in The Secrets of Italian Cooking – Delicacies from the Mediterranean; Kelim, Kelim: the Craft of Tapestry Weaving; Rag Rugs with Rebecca; Sewing for your Baby and other things that might conceivably come in useful for the day when the girls finally got married. Because they were going to get married, no one doubted that. And while you were waiting, you might as well work on your carpet weaving and your decorative needlework. Their parents paid for the courses, and then the girls pestered them for more money for materials. But they only bought one cookbook or one book on conversational English. After that, the book made its way round the girls, who each paraded the same book and the same receipt at home, thereby securing their pocket money for a good while afterwards.

The problems started with the carpet-weaving course ‘From Cloth to Carpet’, when Masha’s parents asked to see the fruit of her labours and all she had to show was a twenty-centimetre scrap.

‘After six months!’ her mum shouted, and started flapping about what she would have to show the relatives, after all her boasting about how her daughter respected the old traditions and could weave her own rugs for her new home.

Who would want to marry a girl who could only weave forty centimetres a year? It would take years before she had any rugs on the floor. Masha had opted for the same emergency lie people used in school when they’d messed up their woodwork project – she whined that someone had stolen her rug and left behind that worthless rag. After that, there were no more carpet-weaving courses for Masha, and no other courses either.

‘You can speak English already, and you get food at home!’

But after a while, their grip slackened again: in truth, no parents have the energy to keep an eye on their children all the time. Often, they handed responsibility to the girls’ brothers, if they had any, and the brothers themselves weren’t particularly interested in keeping an eye on their sisters when they, too, had only just succeeded in getting out of the house for once. They let the girls run around as they wished, with the admonition:

‘Just don’t let anyone see you. If I ever hear word of what you’re up to…’ So it was their job to get along with their honour intact while their brothers snuck off to fuck all those Finnish girls walking about with their midriffs bare, even in winter.

Once they’d all come of age and got bored with reporting where they’d been and with whom, they generally sat in Masha’s room and frightened the wits out of each other with horror stories about forbidden romances gone wrong.

They whipped one another up into a fury with whisperings about girls in their parents’ homelands who’d been killed because some boy had dedicated a love song to them on the radio, or because they’d had the misfortune to be in the wrong place at the wrong time and had been raped. Girls who’d been sent ‘back home’ to get married. Girls who’d gone on holiday to calm down a bit, and never returned. And then, there were the Asphalt Angels. Girls who’d gone out on the balcony, never to return. Girls who overstepped the line and had their lives abruptly ended. It happened to a few. Not all by any means, but you never knew which overstepping would be your last. The worst thing was that it had happened in families that seemed perfectly normal. Families where the situation had gradually escalated, culminating in headlines.

They gazed into one another’s eyes, the silence on the other side of the door was suddenly hair-raising, and they swore on their honour to leave home as soon as possible. After all, how could you know whether it was dangerous to live the life you wanted without ever trying? But when at last Samira was the only one who kept the promise, she just vanished. And Jasmina was left, disappointed and done out of the happy life that was ready to take off any moment, but which always seemed to get stuck before it got started.

Asfaltsänglar

Schildts & Söderströms, 2013

Rights: Salomonsson Agency

We are grateful to the Salomonsson Agency for permission to publish this translated extract.

A review of this novel appears in this issue.

Nichola Smalley is a freelance translator.