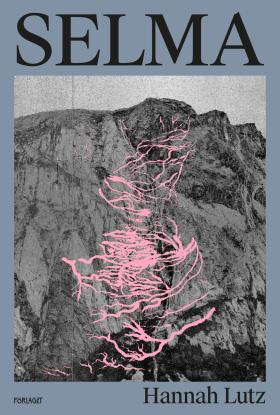

from Selma

by Hannah Lutz

translated by Andy Turner

It is Selma’s 66th birthday, and with that she has become the longest-living woman in her family, having grown up in the shadow of a heightened risk of breast cancer that has stalked her maternal line. Decades ago, after the birth of her daughter, Olga, Selma made the decision to undergo a preventive double mastectomy, a choice that would come to reshape both her self-image and her life.

Over the course of this momentous birthday and the months that follow, Selma looks back over her life, her changing body and her relationships with the women around her, in particular the now-grown-up Olga, from whom she has tried to shield the burden of this risk. This relationship, both close and yet somehow disconnected, forms the emotional heart of the book.

Hannah Lutz made her debut with 2017’s Vildsvin (Wild Boar), a novel praised for its concise, impactful language and interrogation of the complicated relationship between humans and nature. In Selma, Lutz creates an uncompromising, full-bodied portrait of a woman living life on her own terms. By turns tender and seething, it is a book about sharing and shielding, what we let out and what we keep in, living with death and reclaiming one’s life.

This excerpt is taken from the first part of the book, set on Selma’s birthday, as her daughter Olga pays her her second visit of the day. The scene opens with Selma looking out over the café across the street where her friend Vanja works, a focal point of Selma’s everyday life.

from Selma

It is too early for the trouser suit, it is only 14.37. I measure out the coffee, fill the pot with water and pour it in, turn the machine on and wait until I hear the soothing sound of water heating up, the little puffs of steam. I put my jeans on, a blouse, plus a warm sweater and sit down on the veranda with a blanket around my legs. I see Vanja coming out of the café along with a tall woman. Is it Monika? The woman’s hair, curly and down to her shoulders, is slightly wet from the rain, they remain beneath the awning. Vanja lights a cigarette, the woman drinks coffee from a paper cup and gestures with her free hand, they laugh, the woman leans closer to Vanja and takes a drag of the cigarette. But Vanja has many friends, many they share cigarettes with. There’s a knock on the door, two firm knocks. Hello, Mum! Are you home? Olga’s footsteps in the living room, and there, in her spring jacket, she appears. She takes her jacket off and hangs it on a chair. How are you doing? She asks if there’s any cake left, she wants some, Vanja stubs their cigarette out and the woman has gone, Vanja opens the café door. Mum, Olga says, I look at her, is there any left, she says. I clear my throat. Has school finished already? It has, Friday is Olga’s short day after all, I’d forgotten that. Olga is cold, she goes back inside and I follow her through the flat, having had a fervent desire to see her until she arrived. She peers into the bedroom, gives a stretch and pulls at the string, making the bird’s wings flap up and down, looks good hanging there, huh, she says, and I say yes, it’ll get a hook of its own of course. I’ll see to that when I’ve got the time.

Olga sits down on the sofa and reaches for my grey sweater, pulls it over her head and leans back against the cushions. I open the fridge and look at the cake, sunken in the middle, the cream having sagged and congealed again. I attempt to piece together some semblance of a slice for Olga. Coffee? I call over and she calls back, just a half a cup. I take the cup out with little yellow flowers on it, Olga’s favourite, fill it half-way, only it looks rather sorry for itself. I pour some more, kind of right up to the brim in fact, and I carry the tray carefully into the living room and put it onto the coffee table, here you go. I sit down beside Olga. She blows on her coffee and takes a sip, asks how my day has been, if anyone has stopped by. I tell her I met Stella but not about the dip in the sea, I don’t know why, I look at Olga and her long, wet hair, her bushy eyebrows, slightly wrinkled, how were things at work then? All right, she says, I was a little off my game. I don’t know, I guess I was a little worried about you. She looks at me, smiling the way she does when she tries to show concern but doesn’t know how. What do you mean, I say. She shrugs, I thought this birthday might . . . fuck you up a bit. She squints at me. I scratch the nape of my neck. It must be what Stella said the other day. I have really tried to be considerate – when Olga was 18, I told her what was most necessary. I told her about the illness in our family, the specific gene mutation with its dry-sounding name, BRCA2. It was up to Olga if she wanted to take the test. She would have to think on it and process the information in her own space and time. But her decision was instant, the logical thing to do was to take the test. It just had to be arranged, she rang up by herself and made an appointment, I drove her to Helsinki. Later, she wanted to go back to high school even though it was the afternoon by then. It was early winter, I remember, icy in the carpark, Olga walking adamantly back across to the school building.

The following weeks of waiting were agony. I made every effort to hide my fears. Olga didn’t mention the test. When the letter arrived – with Olga’s name on it – she had already gone to school and I was standing alone in the hallway. I moved the letter, unopened, from the doormat to the kitchen table. I was off from work. It was snowing outside, big, wet flakes. I paced up and down the flat. When Radio Vega played Christmas, Christmas, glorious Christmas I turned the volume up full blast and tore the letter open. It hadn’t passed down to Olga, it was as simple as that. I held the letter in my hand, feeling nauseous, shaky. I put my winter coat on and went out into the snowstorm.

I walked down to the harbour with a spring in my step, past Knipan, through Stallörsparken, a thin layer of snow covering the grass and the bushes. Wet flakes were falling into my hair. I was proud of myself, of Olga, of our life, that we were alive. The transformation wasn’t only mine, it was Olga’s now too. I was filled with the same euphoria as I had felt during the time following my operation. Everything was immediate, available. We were free. I wanted to tell her everything. We would cry together, we would laugh, plan a long trip just the two of us. I struggled up the street against the wind, snow in my eyes, I was able to breathe. Inside Mannström’s I bought a roulade, the one with the chocolate filling that Olga loved. The green tableware, candles, I made it special in the kitchen. I cut off two slices of roulade and put them on side plates. She arrived home. Soaking wet with her jacket covered in snow. She gave a brief hello, her eyes red. She hung her jacket in the hall and went into her room, closed the door behind her. Her jacket was dripping in the hallway, fat, dirty drips. I knocked gently on the door, I’ve got good news, I said, my mouth against the chink of the door. Not now, Mum. I could hear her crying. Is it Matti K? What’s he done? Please, go away, Mum. Just go, would you? Leave me be. I stood there, staring at Olga’s door, slowly breathing through my nose. It was already dark outside. I felt ridiculous. What was I thinking? Olga was her own person, clearly enough. She was not the continuation of my story and that was no thanks to me. She wouldn’t be forced to eat roulade, hear about old troubles. The less she knew, the freer she was. She was her own person, and the letter was hers, and life was too. I ate both pieces of cake and blew the candles out.

I have kept the old troubles to myself, the old euphoria, the one I felt following my operation. My body, undefined. Transformed, but into what? A body that was alive, warm, without direction. Without destiny. Conceivable. But last week Stella made such a big thing of my birthday in front of Olga. Now Selma’s the oldest, she was proud of me, your mum has cheated death, Olga, she’ll outlive us all! For Christ’s sake Stella, I wanted to say, but I didn’t say anything.

I look at my knees. Out of the corner of my eye I see Olga stuffing a spoonful of meringue into her mouth. She looks at me and then she looks away again. Forget it, she says, the meringue in her mouth, forget it Mum, I shouldn’t have said anything. I don’t answer, not knowing what to say, and I pick the fine hairs off my trousers, they must have come off the blanket. Sorry, she says, I didn’t mean to make you sad. I’m not sad, I say in the end. I look at her and muster a smile. It was nice of you to come again. Shrugging her shoulders, she asks who is coming tonight as she spoons up the cream from her dish. I ask how her plans for the summer are going. Okay, she says. She looks at me expectantly. She gives a little smile. Good, really. Yes, very well. She plans to go travelling with Angelica as usual, but they will be leaving as early as June. It is going to be a longer trip this year, the geological adventure Olga has been dreaming of for so long. Angelica thinks it sounds exciting. She lives in Stockholm now with her Swedish boyfriend and works as a human resources consultant at some large firm, it isn’t easy for them to get the chance to meet up. Now they will be able to see each other properly. The day after school breaks up Olga will take the train to Vaasa, then the ferry, and then Angelica will meet her in Umeå. They will travel on together from there to Norway.

Olga longs to get about, she longs to get away from here – away from the entire Baltic Shield in fact. She wants to see higher mountains, fells, feel other rock types beneath her feet, high-grade metamorphic rocks, especially eclogite, the most exciting of them all! And composed beautifully of red garnet and green pyroxene, sometimes a little kyanite too, or quartz. This is to be found, of all places, in Romsdal, along the routes they plan to be hiking, and particularly around Ulsteinvik, where you can really see the vestiges of the Scandinavian Caledonides, the continental plates that collided and folded, Baltica which met Laurentia more than 400 million years ago! Her face radiant, Olga smiles, revealing an eagerness that she rarely lets me in on. What she usually lets me see is Olga going about her work, Olga who is perfectly fine and normal, I often think it was a mistake to let her skip a year just because she had an academic advantage. Her teachers were sure enough. Olga was easy-going socially and would quickly make new friends, the important thing was that she didn’t get bored during lessons. And so, she went from third grade to fifth, grew serious and introspective, put her hair up in a tight ponytail. That was when she started going around with Angelica, a friendship I never understood. Olga would be waiting at the door when Angelica was due, then she would shove her into her room and close the door properly. I would hear mumbling, Angelica's timid voice behind the door. What were they talking about? What did Olga see that I wasn’t seeing in this pale, awkward child? But Olga is laughing now, it is no small victory that she has managed to persuade Angelica to hike along the entire Romsdalseggen ridge and then travel on to Ulsteinvik, Angelica who prefers to stay beside the Baltic Sea. They are finally going westwards, and northwards!

And why can’t I welcome it when it does come, Olga’s eagerness, why can’t I be delighted with their friendship? I only think of Angelica’s face, the disinterested look in her eyes, the barely audible greeting I would manage to get out of her as she passed me on the way to the toilet. The pong of fabric softener off her clothes. She is a grown person now, I suck air in through my nose while I listen, nod and close my eyes, attempting to see a grown woman in front of me. One who lives in Stockholm and has a life there, a rich life, with new friends and a boyfriend, a Swede, no doubt a modern, Swedish boyfriend with warm eyes and bright, wide trousers who says: Angelica, fancy going to the cinema tonight? And Angelica looks up, right into his eyes. Yes, she says, loudly and clearly. Yes, let’s! Because Angelica loves film. And she loves Olga. She misses Olga. And now they will go hiking, up and down across the mountains, eating food out of tins and bags. Angelica’s clothes will grow damp and smell of earth, of forgotten bananas, she’ll speak of the nights in Stockholm, the clubs, the frothy drinks that run down your chin and the dance floor where you can let go of everything you thought you knew about yourself. Okay, Olga says, getting up, I’ll be off home to make a few arrangements. It was good, I say, the cake, thank you very much. A little sickly-sweet, huh, says Olga. Yes, well. She smiles and hugs my shoulder. See you tonight.

I get up. I clear Olga’s dish away, her empty coffee cup, rinse them and place them in the dishwasher. I wipe the coffee table, collect the crumbs of meringue in my hands and tip them into the compost and stop and stare into the kitchen cupboard. I am tired, I feel it now. My bed is calling me, but no, then I won’t be back on my feet again this side of midnight. The sofa, it has to be the sofa. It is firmer, better suited for when you just want to shut your eyes for a while. I pull a blanket over me, curl up, sink into half a dream. Even in the dream it is raining, I look up towards the heavens, feeling the rain sprinkle across my cheeks, a deep, cool, never-ending rain.

Selma

Förlaget M, 2023, 200 pages.

Foreign rights: the author.

We are grateful to Hannah Lutz and Förlaget for permission to publish this translated extract.

Hannah Lutz writes short stories, essays and genre-defying prose. Her debut novel, Vildsvin (Wild Boar) garnered praise in Sweden, Denmark and Finland and was reviewed in SBR 2018:1.

Andy Turner is a literary translator and reviewer. Andy received an MA in Literary Translation from the University of East Anglia in 2017 after more than twenty years as a secondary school teacher in East London, Essex and Suffolk. He was the 2018/19 National Centre for Writing's Emerging Literary Translator in Swedish in a mentorship with Sarah Death.