from Build Your Own Coffin

by Robert Åsbacka

translated and introduced by Ruth Urbom

This novel, set in 2018, is narrated by Erik, a freelance writer. Facing money problems after a relationship breakup and career slump, he takes a sublease on a small space in an office building and essentially starts living there. The rest of the office is used by Farkh, a group whose name is an acronym that stands for the Association for Working-Class Culture and History. The ragtag assortment of characters involved in Farkh are ill equipped to cope in today’s dynamic, fast-paced economy embodied in the vast construction site outside, where the surrounding office and industrial buildings are being demolished to make way for gleaming new apartment blocks.

At the suggestion of his Job Centre advisor, Kåre – one of the members of Farkh – decides to organise an evening woodworking class for the group. The theme he chooses for the course is a practical one: Build Your Own Coffin.

Robert Åsbacka uses gentle humour to satirise elements of contemporary society and the increasing commercialisation of all aspects of life, even under a Social Democratic government. While this book is set in Sweden, critics have noted affinities between Åsbacka’s wry tone of voice and the styles of other Finland-Swedish writers including Kjell Westö and Monika Fagerholm.

from Build Your Own Coffin

8.

I’d gone down there many times, down the winding staircase and out. But this time I turned left at the bottom of the stairs instead of right. There was a steel door, painted grey, with no handle. A key was in the lock; a blackened band with illegible writing on it hung from the key. I turned the key and pulled the door open. The winding staircase carried on another floor down. It smelled of timber, sawn timber, and I thought I could hear the sound of a mitre saw… or whatever they were called, those machines with a vertical saw blade. Band saw? They always had them in the school workshop. Sometimes a troublemaker would stand behind someone who was using the saw and chuck a scrap of wood at the blade, causing the wood to go flying across the room. It was hard to say whether the lad was reckless or outright cruel. Someone could have got a splinter in their eye. Someone surely got a splinter in their eye and was now going through life as a blind man.

But there was no noise from a mitre saw or band saw, just the smell and dust.

Behind another closed door was the workshop. As I went in and had a look round, I saw that there actually was a mitre saw and a band saw. And a lathe, a couple of old-fashioned carpenter’s benches forming an L shape in the corner nearest the door, an electric planer, a drill press, sander, electric screwdrivers, and then a wall rack with a set of chisels hanging in order of size, set squares, clamps and manual planers and a number of other hand tools. A large table on wheels stood in the middle of the room, and on the table was a stack of handouts with instructions on how to build a coffin. There were tips and diagrams and lists of everything you could possibly need. When I picked up the papers, they still felt warm from the photocopier. Come to think of it, I had heard someone using the photocopier just as I was finishing up my work upstairs at Farkh before I came down here. Clearly Kåre was serious about this. We were going to build our own coffins. The politicians were nowhere near forming a coalition government, but as Kåre put it, if we waited for them to get through all the rounds of talks and ballots for prime minister, we’d die and get resurrected before we got our coffins built.

A door at the far end of the room opened and Kåre came in. He was carrying a coffee maker.

‘We’ve got to be able to make coffee,’ he said. ‘Can’t keep running up to the office every time somebody wants a cup. So I went over to Lantmännen and borrowed this one.’

He set the coffee maker on a table next to a stainless steel hand basin. Maybe hand basin isn’t the right term; it was the kind of sink used for cleaning paintbrushes in. I guess we’d be needing it. We’d be painting our coffins, right? Or varnishing them? You didn’t see them in unfinished wood – although now I thought about it, it seemed a bit unnecessary to paint and varnish something that was going to end up in the ground or in a crematorium oven.

‘I thought Lantmännen had moved out,’ I said. ‘The place looks vacant, and the letterbox is overflowing with junk mail.’

‘Oh yeah, they’ve moved, or rather, the office has moved. The production facility is still there, a bit further down,’ Kåre said with a vague nod towards the door, ‘but the office people left a whole load of stuff behind. Several coffee makers in a cupboard, so that tells you how they spent their days. But the coffee makers were all in good shape as far as I could tell. This looked to be the best one, and it uses the same size filters we’ve got upstairs.’

He plugged in the coffee maker, filled it with water and switched it on. It started chugging, and I immediately felt a craving for coffee. My left eyebrow was aching. But there was no ground coffee in the workshop – not yet. Maybe I ought to go upstairs and fetch some. If none of the others thought to bring some down. We had agreed to meet downstairs at seven o’clock, and it was now ten to seven.

‘Hmm’, Kåre said, patting the coffee maker, ‘seems to be working all right, even after all those years at Lantmännen. Not everybody survives a tour like that.’

There were no windows. It was like being in a bunker. I wondered how the ventilation would work. But I supposed it must be in good order. After all, the previous tenants had used the space for woodworking for many years. Heavy-duty leads ran from the lathe and mitre saw, and when I looked more closely, I noticed ductwork on the ceiling leading out through the far wall. Presumably there was some sort of fan or ventilation unit on the other end. A dust collector?

‘Build it and die,’ Kåre said. With that, he pulled up a stool and sat down at the table. He put his hand in his pocket and pulled out a handful of salted pretzel sticks, which he placed right in front of him. He seemed to think for a moment, then pushed the pretzel sticks over to the right and reached for the stack of handouts. He started sorting through them, licking his fingers every so often. He arranged the sheets in separate piles as he rattled off names: Hoffman, Vide, Sonja, Erik, Tim… and Kåre.

When he had finished, he counted the piles.

‘Six,’ he said, ‘and I suppose that’s everybody.’

‘Tuomo?’ I asked.

‘Eh,’ Kåre replied, ‘he says he’s here all day and that’s more than enough. Besides, his time here is nearly over. He’s retiring in a few months, so he is focused on sleeping through the remaining weeks between eight and four. No evening shifts for him.’

I had never met anyone capable of sleeping so much. Wherever there was a sofa, there was Tuomo with his head supported by a pillow, blanket or even a pair of shoes. He’d usually lie on his side with his legs curled up and both arms tucked beneath his head. Shortly after I’d signed the lease on my office, I came in a bit later one day – getting on for 10 o’clock – to find Tuomo asleep on my sofa. Legs curled up and arms under his head. Apparently the door had been unlocked and Tuomo had peeped in, seen an unoccupied sofa and gone in for a lie down. But because I insisted on sitting in my office and working during the day, he had started to seek out a quiet spot in eBladet’s editorial department. There he would lie and doze away most of his working days.

I leafed through my handouts. Building a coffin didn’t seem all that easy, even if you wanted a simple model. Clearly it still needed to be sized somehow to fit your body, wider towards the top and narrower at the other end. At least that’s how it looked, judging by the diagrams. But not everybody looked like that, in bodily terms I mean. Of the people who were going to be doing the course, Vide was really the only one who fit the pattern. And maybe Tim. Though he was more narrow all over. Going by that logic, if we were going to tailor them to our dimensions, Tim would have the easiest job. Basically all he’d have to do was nail together a box with straight sides. The handouts indicated it was more complicated than that, though.

‘Hey, Kåre,’ I said, ‘if you look at this…’

I held up a page with dimensions and angles, clearly showing that a coffin should be wider towards the top end.

Kåre held up one hand, a bit like an old-fashioned traffic cop.

‘We’ll deal with that when everybody’s here,’ he said, ‘otherwise I’ll have to sit and explain the same damn thing all night.’

[…]

The sound of footsteps came from the stairway, like an entire army on its way down. Or maybe not an army, but a school group on their way to their first woodworking lesson. They were talking loudly, the three of them: Vide, Sonja and Tim, the youngster, barely over forty. I hadn’t seen Tim in a while. I tended to think of him as a wonky Northern second cousin of Mick Jagger. He’d always been skinny, at least all the years I’d known him, and now he’d got even thinner. His natural paleness had gone over to grey. The Tim who entered the workshop looked like Mick Jagger risen from the grave. And now, fittingly enough, he was going to build himself a coffin.

That thought made me snort a laugh that found its own way out unbidden. The others stopped mid-sentence, looked at me and smiled, as if waiting for me to share the joke with them.

‘What are you laughing at?’ Sonja asked.

She looked down at herself, seeming to search for something wrong, missing, torn.

‘No, it’s nothing,’ I said, ‘just something that occurred to me. It doesn’t matter.’

‘My brother,’ Vide said, pulling a chair over and sitting down close to me, ‘go on, tell us. We want to have a laugh together, like real compañeros.’

Vide had a habit of sprinkling his conversation with Spanish words. He and a few other people, most of them probably from the Swedish-Cuban Association, spent a few hours each Sunday learning Spanish. Sometimes when I headed to the kitchen or bathroom on a Sunday afternoon I’d find them sitting there, a group of middle-aged and older men reading words to each other. They did it not because they longed to visit sun-drenched beaches but because they loved Cuba and anything at all related to the notions of Latin America, socialism, revolution and anti-imperialism. If I hadn’t seen them with my own eyes, I wouldn’t believe they existed. I’d actually gone through life believing the admirers of Che Guevara, Fidel Castro, Castro’s brother and their ilk had died out in the early eighties. Well, not literally died out, but come to their senses and re-evaluated and reformulated their revolutionary fervour into some sort of reformist socialism that was more widely acceptable. But they existed, and I guess their admiration for Castro had been transferred to some extent to Hugo Chávez and his dysfunctional successor Nicolas Maduro. I generally had a hard time with the left that idolised Latin American men in uniform. But Vide really walked the walk. Throughout his entire career, he refused to negotiate a higher salary. He didn’t drive a car; his mobile phone was an ancient model held together with tape; he donated a large portion of his income to organisations like the Swedish-Cuban group; he demonstrated in support of his beliefs, supported lone immigrants and refugee families, contributed to Farkh’s library from his own resources. He read constantly, played in two blues bands and was involved in the trade union. Plus he had managed to keep a long marriage going and was friendly with his grown-up children.

But there was just the fact that he really believed in socialism. As a social democrat, I found it difficult to feel an affinity with that sort of person.

I didn’t need to explain what had made me laugh. Vide had barely finished saying his ‘compañeros’ when Kåre rapped a piece of wood on the table and declared the meeting open. Silence fell over the room. We were all schooled in the running of meetings, finely drilled association denizens.

‘Build your own coffin,’ Kåre said. ‘The diagrams are on the handouts in front of you. Have a look through, and then we’ll discuss how we’ll go about it. Sonja and Tim can read together.’

‘Out loud, you mean?’ Tim asked.

[…]

[...]

‘How are we supposed to know what to do when we don’t know what to do?’ Sonja asked. ‘I don’t know how to use any tools. I thought you were going to teach me. That’s why I’m here.’

‘You said it,’ Vide agreed, then turned to Kåre. ‘Now why don’t you step up and explain instead of just telling us to go home and imagine how our coffins will look. Like the power tools. Are we going to use them? And how are we going to fasten everything together? Nails? Screws? Glue?’

‘How are we going to have room for all the coffins in here?’ Sonja asked.

The space was not large. I estimated it at around twenty-five square metres, about the size of my old studio flat.

‘We’ll assemble one at a time,’ Kåre said. ‘Everybody will get started and design and plan and make the parts, sawing and cutting and all that, and then we’ll put together one at a time.’

‘So whose are we going to put together first?’ Sonja asked.

‘To each according to their needs,’ Vide said.

‘But everybody needs a coffin,’ Sonja said. ‘That’s why we’re here.’

‘All right,’ Kåre said, ‘this is what we’ll do: when the time comes, when we’ve got far enough that we can actually see a coffin might take shape, we’ll draw lots.’

‘I didn’t know I was going to be in some damn lottery,’ Vide said.

‘All right then,’ Kåre said. ‘We’ll build yours last. Any other questions?’

I looked down at my handouts as voices buzzed around me. There was a list of steps to follow: first you do this, then you do this. The first item was to get your materials and your tools, so I skipped over that. We had the tools, and we’d already discussed materials. Although I wasn’t yet sure what I was going to use. I wanted something good and sturdy, ideally nice-looking as well, but I wasn’t prepared to pay all that much. Well, prepared wasn’t the right word. I wasn’t able.

‘I was thinking about the bottom,’ Tim said. ‘It must be important not to have it drop out…’

‘You’re on to something there,’ Kåre said.

‘… so I guess you can’t just glue it?’

‘Glue, screws and battens,’ Kåre said, ‘but we’ll get to all that in good time. It’ll sort itself out. All you’ve got to do is build it and die – nothing more to it than that.’

Kistmakarna

Schildts & Söderströms, 2021, 316 pages.

Foreign rights: the author.

We are grateful to Schildts & Söderströms and Robert Åsbacka for permission to publish this translated extract.

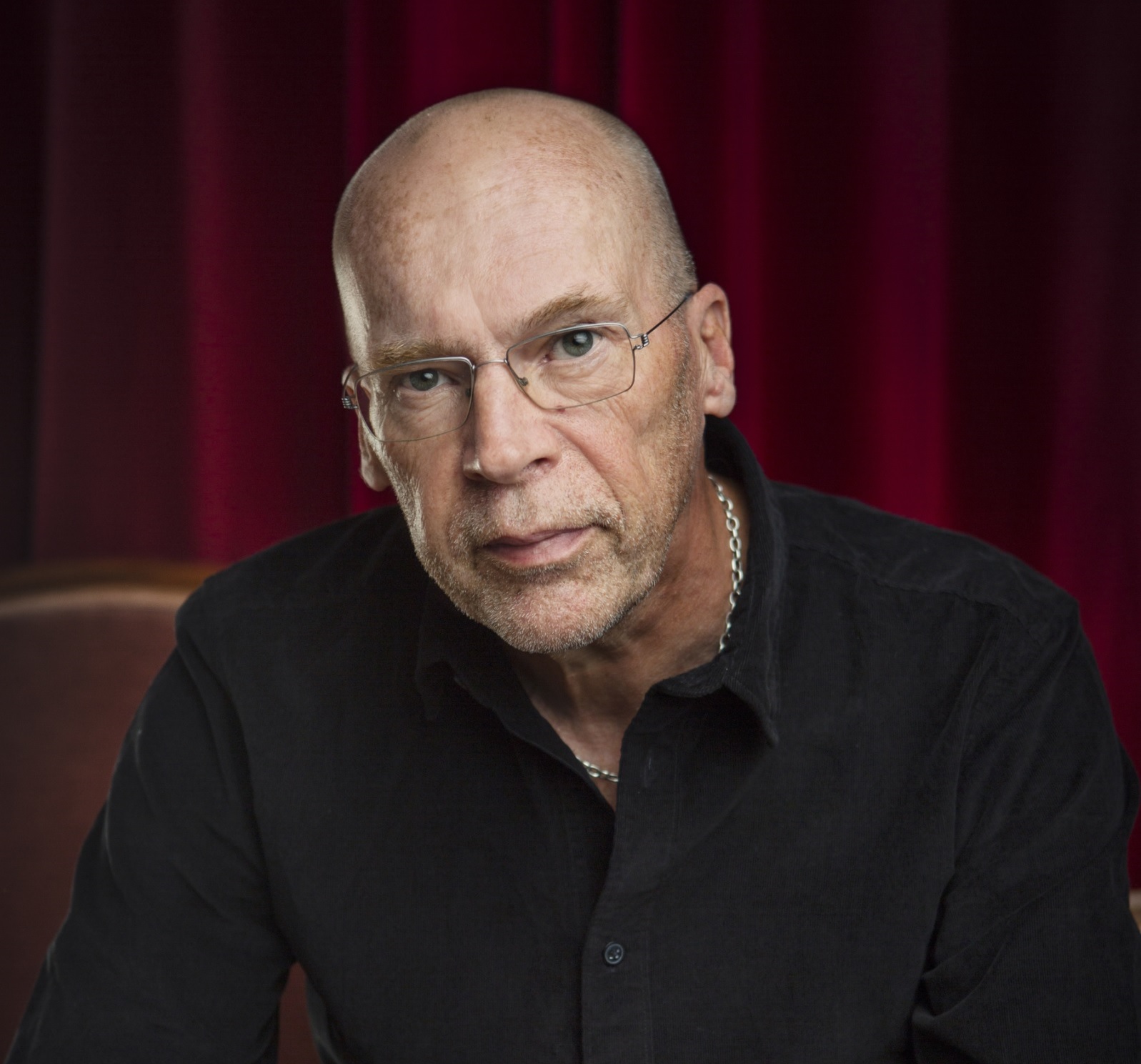

Robert Åsbacka is a Finland-Swedish writer based in Eskilstuna, Sweden. He is a two-time winner of the Swedish YLE Literature Prize, and in 2022 he was awarded the prestigious Karl Emil Tollanders Prize by the Society of Swedish Literature in Finland for Kistmakarna. His novels Samlaren (The Collector) and Orgelbyggaren (The Organ Maker) were reviewed by Željka Černok in previous issues of SBR.

Ruth Urbom is a Chartered Linguist. She was Chair of SELTA from 2012 to 2018.