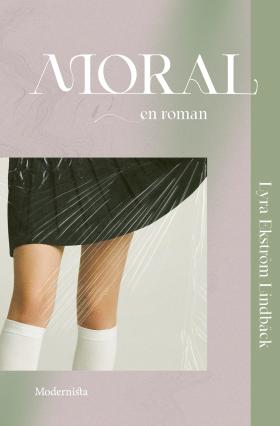

Moral

(Morality)

by Lyra Ekström Lindbäck

reviewed by Emma Olsson

Anna leaves Stockholm for Prague to study ethics – the philosophy of morality – and commences a full-immersion academic study. She starts an affair with her supervisor and yes, he is married. But is it just by accident? It would be a bit too on-the-nose, wouldn’t it, given her PhD topic of choice? Early in the novel, Anna, a writer of fiction, describes her interest in literature and its relation to ethics, the murky ponderings that lead her to apply to study under a man whose work she has become infatuated with. She addresses him rhetorically here:

'What does literature do to our ethical reflections? Does it always disturb them in a terrible way, as you seem to think? Is inspiration actually a force for good? Can novels that make something bad appear meaningful also be morally constructive, at least clarifying?'

Moral (Morality) unfolds like a thesis centred on these questions.

At the university, mature and serious Anna goes full Lolita-meets-Lana Del Rey, even donning knee socks in class in the middle of November. She locks her supervisor’s office door behind them for an intimate feedback session, sends flirtatious texts mid-seminar, and applies red lipstick. She feels like 'a manga character, a schoolgirl, a porn fantasy', but the fabrication of this feeling is deliberate, even if the roots of her desire to present this way are obscure. She’s not really sure why she’s pursuing this relationship. She’s queer and hasn’t been with a man since high school, and certainly isn’t in love with her supervisor – she isn’t even particularly attracted to him. It’s a philosophical game. When the charade is up, when her new persona ceases to excite her, making her feel silly and exposed, the game progresses to the next level. Anna tries out philosophical arguments like new hosiery.

Ekström Lindbäck’s measured style suits the moral exercise present in these pages; I think she’s the strongest she’s ever been as a writer. She shines in an almost academic style that can sometimes feel stiff in novels like Blödningen (The Bleed) from 2020, but perfectly fits the bill for the type of story Moral wishes to tell, where each question becomes a research statement, and a conceit is planted only to be deconstructed.

What I found missing from the novel was fun, something I’d come to expect from this kind of story (you know, the one where the student sleeps with her teacher and all hell ensues). This might not be a bad thing. Moral has no racy romps or coquettish banter to propel it forward. It only has the facade of racy romps and coquettish banter. And it lacks the predictable moral reckonings we often see in novels with similar subject matter. There is no moment when Anna stops herself, lost in the heat of passion, to decide she’s finally taken it too far. That’s because there isn’t much heat of passion; their trysts feel awkward and cringeworthy, as hypersexual and pornified as Anna’s new persona. Instead, and cleverly, Moral also offers the facade of these moral reckonings. Almost from the start, it feels like Anna is going through the motions of an affair, heading towards a climax of the big reveal. It’s clear that what interests her is the implications of her actions: What will they be? How will she feel?

The question of power, ever-so popular in our culture, is handled well. Many novels of this genre foreground the imbalanced power dynamic between an older male professor and younger female student. Contemporary novels like Vladimir by Julia May Jonas play with this trope by reversing genders, but many great novels like Eimear McBride’s The Lesser Bohemians focus on what it means for a younger woman to enter into this type of precarious relationship. In Moral, the fraught power dynamic between Anna and her supervisor isn’t so much explored as just mentioned. It’s presented with a shrug – duh, of course – through a conversation between Anna and her childhood friend. As millennial/Gen-Z cusp women they are well aware of the presence of unequal power dynamics in their lives – they came of age with these questions – and don’t take much interest in interrogating them. That doesn’t mean they don’t hurt, though. You get the sense that Anna suffers through the relationship. It is her status as a writer that starts to tip the scales of power with her ability to reveal truth, and the question returns to that central thesis expressed at the start of the novel.

Ekström Lindbäck has written an ideas novel. Those expecting a fun plot might wish to steer clear. Smart and austere, I wanted a break from the prose at times, but as I write this, I can’t imagine another way to tell this tale. Moral plants seeds in the mind. The fun comes from watching them blossom into strange flowers.

Moral

Modernista, 2023

192 pages

Foreign rights: Emiliano Sener, Modernista

Nominated for the 2023 August Prize for fiction

Lyra Ekström Lindbäck is a writer and critic. Her novel Ett så starkt ljus (A Light So Strong) was reviewed in SBR 2015:1. An extract from Blödningen (The Bleed), in Emma Olsson's translation, appeared in SBR 2023:1.