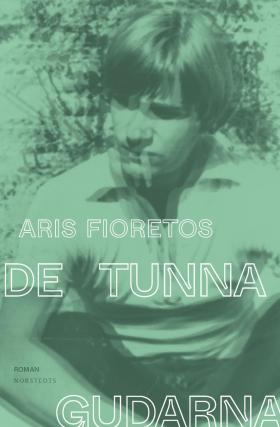

from The Thin Gods

by Aris Fioretos

translated by Tomas Tranæus

Since his literary debut in 1991, Aris Fioretos has become one of Sweden’s most respected authors. Over the course of his career he has published a wide range of works spanning novels, essays and scholarly studies, and he has been translated into over a dozen languages. With his most recent novel, De tunna gudarna (The Thin Gods) Fioretos turns his attention to the rock scene of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, as seen through the eyes of Ache Middler, an ageing US musician coming to terms with his own pride and faltering dreams in an industry obsessed with youth.

Written in the form of letters to the daughter whom he has never met, the twenty chapters that make up the novel take us from downtown New York to Thatcher-era London, new-millennium Berlin and beyond, describing the rise and fall of an artist devoted to music. Impressive in scope, the novel is at one an elegant ode to the music of the era and the cities that cultivated it, and an astute, unflinching portrait of an artist’s endless search for something greater. Fioretos's next novel, entitled Yellow and due out in late 2026, will offer a sequel of sorts.

In this excerpt, following the loss of his twin brother Jim to a drug overdose, Ache quits New York in favour of London, in search of the sounds that will make sense of this new stage in his life. It is there that he reconnects with a former acquaintance, Edie Reid, a relationship that will come to be formative for him. This is a relationship that is mapped out on London’s streets, and that plays out to the music of the times.

from The Thin Gods

Rain, Sidewalk

Jim’s death made me invisible. Not that I vanished from the world. I had arms and legs, head and heels. But I felt off – like a retard, in my brother’s parlance. Although I’d behaved like an only child since moving to New York, I noticed that I’d been counting on him the way I did on air or light. No matter what I’d thought, what I’d done, it had been in the knowledge of a twin brother who in the same instant acted or thought somewhere else. When he was buried I lost that certainty.

They say the dead have no shadow. I became the one Jim left behind.

The new album would have to wait. Until I’d found the sound for a world without brother I preferred silence. Still, to bear it I bought a notebook I filled with free-flowing talk. It became my way of moving on: mute but blabbing. One day as I was leafing through it, lying on the bed, I came across a word I couldn’t understand. It had been crossed out and half-replaced by another word. After that I called these attempts to maintain contact monodialogues. Today I wonder if that word isn’t better suited to my lines to you.

It’s difficult to talk about this period. Back in New York I let time pass. I know, it sounds vague, but I assure you: nothing was vague. In death Jim taught me that he’d always been there. Or better: his voice. Often it swore or joked in the back of my head. At times, though, it floated through the air, like when he used to smoke joints in the Impala. Or else it mumbled like when we imitated Joe Friday, sitting with Nana in front of the TV: ‘All we want are the facts, ma’am.’ This ghost of a voice; nothing was more trustworthy. Or more difficult to capture. Now I became afraid of losing that as well.

Life darkened like an old photograph. I stopped getting in touch with people, lost the number to friends. I had always been something of a dreamer – I still was, just without dreams. One late night in Koreatown I noticed that I didn’t know how I’d ended up next to the aquarium in the restaurant. Fishes with scarlet veils for fins moved serenely through a world next to mine. I realised I was becoming the sort of person Nancy had said only inhabit their lives. Soon I would have spent the greater part of my life within a few square miles on lower Manhattan. Time to go away.

When the agent I still had – why, I could no longer tell – arranged a contact at Virgin Records, I knew where to.

London wasn’t the same city it had been when Transmission played Olympia in the summer of 1977. The miners’ strike had recently ended; under Thatcher, privatisations continued.

There were several bands singing about the state of the country. I liked their cocky lyrics and desperate energy, but musically the songs were as uninspiring as the syrup on the radio. No one seemed interested in pushing boundaries, almost none of the groups sounded original, everyone was out to please. After a couple of weeks I stopped going to gigs and spent my evenings in the pub. Now and then I met someone to spend the night with.

Virgin were pleasantly half-hearted in a manner I couldn’t quite figure out. After some negotiating they promised to cover the cost of a demo provided I found an affordable studio. The industry was ‘changing’ at the moment, the market was facing new ‘challenges’. Vinyl was still king, but there were young, exciting ‘formats’. Also, MTV demanded ‘investments’. They looked forward to keeping in touch, if I needed anything I just had to give the secretary a ‘ring’.

The mixed messaging puzzled, but didn’t alarm me. Until I had songs that were good enough I wasn’t about to go into the studio anyway. The material needed to mature like a conviction. Once Virgin heard where the music had taken me they wouldn’t hesitate. Instead I wandered around the city. Sometimes I got so thoroughly lost I had to take a taxi back to the doll’s house of an apartment the record company had arranged for me. Other times I got on the bus at Warwick Avenue, rode it to the last stop and then returned a couple of hours later with chord changes in my head. Still, I only wrote down melodies that survived a night’s sleep. The album I carried within me as others might an illness would deal with the tenacity of loss.

The arrangements became clearer over the winter; as the lilies were sprouting I contacted producers. I spoke to three or four before settling on Danny Boswell. Virgin liked my choice: Boswell stuck to the budget and had, though still under thirty, worked with several successful bands. For my part, I appreciated his ear. Even if the groups he had produced weren’t to my taste, the sonic image was always clean and distinct. Apollonian.

That’s how I met Edie Reid again. I had just visited Maison Rouge Studios in Fulham. When Boswell, who liked jazz, showed me the spacious sounds that could be made there – the studio was in a converted church – I became convinced: this was where I wanted to record.

Now I was hurrying to the tube with a wet cigarette in my mouth, animated by the thought of recording songs in what had once been a sacred place. At first I didn’t give the woman who crossed the street holding a mushroom-shaped umbrella a second thought. The rain slid down the yellow plastic canopy like flickering gold, the figure below it so thin her coat looked dry. As she brushed aside a slippery strand from her forehead I recognised the face, but had difficulty placing it. Eight years had passed since Edie had interviewed me in New York, and she hadn’t dyed her hair blonde back then. Or worn it straight. I thought it safer not to greet her. But she pumped her umbrella up and down as if the world had to be stopped in its tracks.

‘My God, Ache Middler? The Ice King?’

A car horn blared. Edie was standing in the middle of the street, peering in that way I now remembered, as if with eyes waiting to be born. When the car honked again she put her sunglasses back on, convinced. She hurried across so quickly that her umbrella got pressed into my hand. Startled, I took it. When we brushed cheeks her hand flew up to fix something with her hair, then she announced she’d only be a couple of minutes and promptly disappeared towards Maison Rouge.

I stood there with the ludicrous plastic dome above my head, unsure of what had just happened. If I hunched my shoulders the rain only hit my elbows, but in return I looked like a human lamp. I shook out another cigarette, which barely got wet before Edie returned. Boswell didn’t need her for the day’s layering. When she took her umbrella back I noticed she had refreshed her lipstick.

It continued to rain throughout the day – as we had a cup of tea around the corner, took the District Line to Paddington, where we ate, and ended the evening in a pub near my stop. The dress Edie was wearing shimmered so improbably the fabric seemed woven of steel and sky. It was still wet at the hem, which made her knees seem fabulously naked. How her skin glowed ... By now I knew not just that she was sharing an apartment with a Belgian student and had a boyfriend who was doing a doctorate in Norwich, but also that she was afraid of going blind. When I asked if it wasn’t treatable she explained that surgical interventions made her even more afraid. ‘Thanks, but no thanks.’ If the light was too bright she wore shades.

Neither one of us said anything as we left. Fifteen minutes later we were lying in my narrow bed in Maida Vale. […]

We kept work and personal lives separate, so when I started recording at Maison Rouge Edie always found something else to do. Boswell said nothing, even if he perhaps wondered about our behaviour. If I was warming up at home, however, she would lay on the bed, leafing through the books I’d bought in second-hand bookshops in Bloomsbury. Sometimes she would comment on what she was reading. Or else she would talk about Danny who probably fancied her, because when he’d asked if there was something going on between us he had sounded unusually stiff, almost defensive, and put on an Ella Fitzgerald record. He always did that when he felt sorry for himself – preferably one of the duet albums with Joe Pass. Before then I had never managed to work in the presence of someone else, much less tease out harmonies after having heard something on the radio. But with Edie I could.

‘Golden haze’, I whispered one morning when Dusty Springfield was playing on the radio. While Edie lay with a pillow pressed to her belly, as if she were pregnant, the chords on ‘The Look of Love’ had drifted through the room. Even though I’d turned the radio off, they lingered. This warmth, so gentle but not brittle, this strange, lingering reverberation – that was the feeling I was after. My fingers continued skating along the strings, the sounds turning increasingly ethereal. Yes, drawn-out notes ought to be the secret principle of the demo.

Edie squinted. Were there any lyrics to the tune I was working on?

I played it again. No, not yet. Maybe never? Or else it would be enough to sing ‘golden’ and ‘haze’ so many times the words settled in layers, creating their own glimmering mist. That, at least, was how I imagined the kingdom my brother had sought for reasons I would never comprehend. Each note rang out in knowledge of the others; when the last one faded it was in memory of them all.

Edie disappeared into the hallway. ‘Like gold to airy thinness beat ...’ Having pulled her coat on, she found her sunglasses. As she plunged her hands into her pockets, it looked like she was holding squash balls. ‘Shall we go?’

I didn’t know what had come over her; she only smiled ruefully when I pulled on my beret so my ears stood out. It was only later I understood that she had quoted one of the most famous poems in English literature. Then I christened the song born that morning.

Out in the street Edie inserted her arm under mine. We walked stooped slightly forward in the rain, unsure but for different reasons. At Rembrandt Gardens she loosened her grip. Her movements were stiff, her voice thin as we continued across the canal, towards Paddington Station. ‘I thought you were the kind who manages on his own. It seemed that way in New York, in that restaurant whatever it was called.’

‘Cairo.’

‘Mm, Mr Ice King takes care of himself. Likes groupies and trashing hotel rooms with the blokes. But in the fight for the future of rock’n’roll he only trusts himself.’ She tugged at my sleeve as if asking me to stop, but when I did she kept walking. ‘Same thing on the Fulham Road.’ Although the reunion had pleased her, she had sensed I was a threat. She had hung out with enough musicians who were blithely self-absorbed. Still, she thought the ‘crowding’ or whatever I called what we had devoted ourselves to on my narrow bed was worth it.

I didn’t know what to say.

The drizzle had intensified. It was only when we reached Kensington Gardens that Edie broke the silence again, looking around with a lost expression. ‘Oh, I’m such a mess, Ache. Every step forward feels like two backwards.’ She lifted her gaze without looking at me. ‘I promised Anouk not to say anything, but now I am.’ Her hair hung around her face, her teeth glistened. ‘I don’t think you’re dangerous. Women notice that kind of thing. You just haven’t learned how we work. So now I’m scared. Now you can really do damage.’

We walked past heavy, wet trees and heavy, wet lawns on which ducks waddled like despondent regents. Even my tongue and lips felt heavy and wet. To get out of the rain I pulled her under a tree – drops hissed as they slid through its crown. Edie looked so helpless, having spoken the way people do when words mean only what they ought to.

‘Can you ...’ I was going to say: ‘teach me.’ But it came out: ‘save me?’

She took a step to one side, then directed her gaze at my hairline. Now she glowed like a complete sun.

That night Edie admitted she had told Adam about me. Just a few days after our first night. Her old boyfriend had even been in London – to sort out ‘the situation’, as he put it. She hoped I wouldn’t take offence, then she snorted into a handkerchief by pressing a finger alternately against each nostril. No, she wasn’t going to see him again. ‘But it’s impossible to cut ties just like that.’ Some days it would hurt and sometimes she had to be sad, that was something I just had to put up with. Now that she knew where I stood everything felt better. ‘We’ll be each other’s salvation.’

Even if the words sounded thirteen years younger than the ones I would have used, there was something liberating about their sincerity. Before we fell asleep I told her about the voice inside my head; wordlessly Edie put her arms around me. When we woke up in the same position the next morning a great tremor passed through me. A longing. A weariness.

For the first time I didn’t hear Jim.

De tunna gudarna

Norstedts, 2022, 500 pages.

Foreign rights: Liepman Literary Agency.

We are grateful to Liepman Literary Agency and Aris Fioretos for permission to publish this translated extract.

Aris Fioretos is a Swedish writer and translator. He is the author of numerous novels, essays and scholarly studies, which have been translated into over a dozen languages. He has received numerous prizes and awards, most recently the Swedish Academy’s Essay Prize and the Order of Merit from the Federal Republic of Germany. Since 2010 he has been a member of the German Academy for Language and Literature in Darmstadt, where he served as vice president for nine years; since 2022 he has also been a member of the Academy of Arts in Berlin.

Tomas Tranæus writes in and translates between Swedish and English. He has translated several works by Aris Fioretos into English, including Flight and Metamorphosis, a biography of the poet Nelly Sachs. He lives in Lisbon.