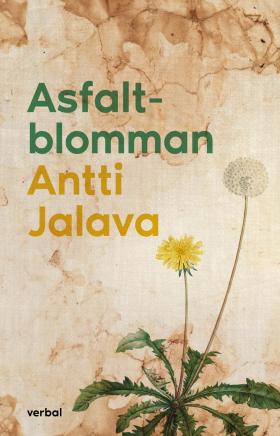

Asfaltblomman

(Asphalt Flower)

by Antti Jalava

reviewed by Darcy Hurford

Sweden and Finland share an enormous amount of history, which does not always go acknowledged. Most obviously, Finland was under Swedish rule until 1809; less obviously, people have always moved between the two countries. An estimated 700,000 people in Sweden today have a Finnish background. While Finnish-speaking minorities have existed in Sweden since earlier times, in Norrland for example, the wave of migration from Finland in the 1950s was particularly large and significant. As of 1954, the ‘right to work’ was introduced for citizens of Nordic countries, allowing them to live and work in any other Nordic country without needing a work or residence permit. Unemployment was high in Finland while Sweden was, comparatively, booming, so many crossed the Gulf of Bothnia in search of work.

One of them was Antti Jalava, who arrived at the age of 10 with his family. Asphalt Flower, originally published in 1980, out of print and now appearing in a new edition due to increased interest in Sweden Finnish identity, is a multilayered novel with two main strands. The first is that of a bildungsroman: Erkki Kataja, who has a series of manual jobs, is working on a novel about Hannu, a Finnish boy who moved to Stockholm. The text glides between Erkki’s day-to-day-life and episodes of Hannu’s story. The second strand relates to Sweden Finnishness, specifically the issue of language. Finnish and Swedish are not mutually intelligible, and children arriving in Sweden in the 1950s onwards were typically forbidden to use Finnish at school. This is a central trauma for Jalava and Hannu. In the novel-within-the novel, Hannu gradually loses his Finnish skills, and with it his sense of identity. Along with self-hatred, he also develops a sense of repulsion towards the new language forced on him:

Hannu is now actually outside language, he’s not monolingual or bilingual or semilingual, he’s just alingual, he has no language to inhabit. The language that held the experiences of his first ten years is now trampled flat. The new language they’ve tried to put in the first one’s place is cold, mechanical, hard, without feeling and very repugnant. It’s not a language.

Ultimately though, Hannu’s story ends on an upward note, even if it is abundantly clear how alienated he feels in Sweden. After hitchhiking around Europe and America, he returns to Sweden and enrols in night school. Similarly, Erkki’s novel is reaching completion and he gets translation work.

Erkki knows Finnish, though. Which does not make him any less of an outsider: he goes to Finland and in Ostrobothnia meets a war veteran who makes it evident that Erkki is not part of the ‘we’ that was in the war, while in Sweden he is not fully considered a Swede. But it does give him a stronger sense of identity than Sirkka, with whom he starts an ill-fated relationship. She is also the child of Finnish workers, but doesn’t really know Finnish that well, and neither has she integrated into Swedish society. Another example is Pirkko, Sirkka’s sister-in-law, whose goodbye letter to her ex, Juha, opens the novel. Pirkko followed Juha to Sweden but felt so out of place she is now returning to Finland. But loss of language is a central theme even as Erkki writes a novel in Swedish:

What I didn’t get from Swedish, I looked for in Finnish. And if only Finnish had covered the reality that was mine, the exterior and interior, I obviously wouldn’t be writing in Swedish.

This is a fascinating novel in many ways, and uncomfortable in others. It puts its finger on the cultural cringe Finns can feel in Sweden (particularly in a scene where Erkki, Sirkka and Sirkka’s mother have coffee with their Swedish landlady). It also has a very 1970s feel to it: the kitchen-sink elements (violence, visits to the launderette, hair washing with washing-up liquid), the seeming ease of moving from job to job, trade unions and the existence of night school. There is also a fair bit of violence and alcohol, but more importantly – and this was Jalava’s particular contribution as a writer – encouragement to Finns in Sweden to be proud of who they were and to remember they weren’t just a workforce, but actually people. The writing style feels fresh and direct, and the author’s tendency to insert Finnish words and phrases here and there with no concessions to a Swedish-speaking reader feels ahead of its time. There is also a lot here that anticipates literature by more recent writers whose heritage also reaches outside Sweden.

Asfaltblomman

Verbal förlag, 2024, 220 pages

Foreign rights: publisher

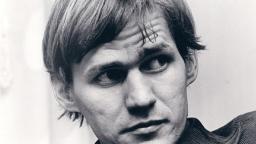

Antti Jalava was born in Lappeenranta, Finland and moved to Sweden at the age of ten with his family. Asfaltblomman (Asphalt Flower) was the first in a trilogy that also included Sprickan (The Rift, 1993) and Känslan (The Feeling, 1996) and had been out of print until now.