Omsorgslabyrinten

(The Maintenance Labyrinth)

by Ida Börjel

reviewed by Darcy Hurford

We begin in Room 416. ‘You can go in,’ says the first speaker, adding that they have their things here on a small trolley. There follows a detailed list of these things: everything from microfibre cloths to goat-hair brushes to smoke sponges and white cotton gloves (‘they need to be washed regularly / so cotton is easier’). ‘Omsorg’ means ‘care’ or ‘maintenance’, and the ways in which museum exhibits are cared for is very much to the fore. Remarks are made about some of these tools. Bread was once used instead of smoke sponges; the Vatican has strong views on saliva.

Omsorgslabyrinten is full of such unfamiliar details. It’s a trip around a museum, but not as we would usually expect to see it. On the one hand, there is utter precision as to materials and techniques; on the other, a chatty matter-of-fact tone. From the first room we move into another, and then pass along a corridor of mirrors, and at around one-third through the book, into ‘Hill’s Cave’, a room housing the enormous collection of art left by the artist Carl Fredrik Hill (1849 – 1911). Here the tone changes, the language becomes more disjointed – possibly reflecting Hill’s state of mind as he created it (he was diagnosed with schizophrenia), and shifts into a more experimental mode, first with a letter from Hill’s father, who thought the spelling of the Swedish language would be more efficient if the vowels were left out (‘Dr Crl!’ the letter begins), and then into old-fashioned rhyming poetry.

The next chapters return to the curators, first to their break room, and then in a lift, and then we take a shortcut into the heart of the museum: here are paintings, and numbered footnotes describing damage to them. Then a corridor (‘We’ll just carry on’), then textiles, then a chapter called ‘Aria’ where a mystery textile is studied, commented on and returned to its place. The collection ends with an ‘Appendix. Status reports’: a factual description of exhibit items and their condition – yet without mentioning what the item actually is.

Relayed like this, the book might sound as dry as an exhibition catalogue, As an actual reading experience, though, it is not. There’s a kind of layering effect in reading about all the different exhibits, all the remarks and thoughts about conservation that build and expand on each other, that brings the museum to life. And awakens a few thoughts: How do we look after the past? How do we relate to objects? Do we value museums as much as we probably should? The labyrinth of the title can be understood as a reference to all the routes taken through the museum building, but also more abstractly as a labyrinth of choices: how to conserve, what to conserve.

Although the book is structured as a tour of a museum – Börjel based it on time spent at Malmö Art Museum – it is told not from the perspective of a normal museum visitor, but from the perspective of curators, of experts who work to preserve the exhibits, have done so for many years, and can draw comparisons with museums elsewhere. A perspective not often heard or appreciated. To curators, the exhibits are not simply works of art, but physical objects that need to be looked after in specific ways depending on material and age, and this physicality is a recurring theme. One point, repeated at intervals, is that conserving objects is about making sure nothing happens: no damage by silverfish, humidity or other hazards. Unexpected aspects of objects are interesting to curators too:

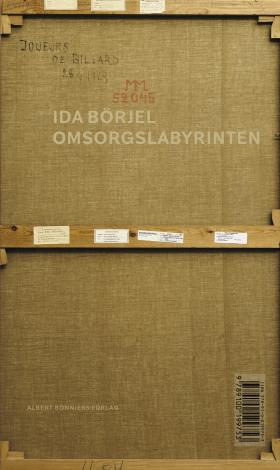

The interest in the back of the objects

that’s a curator thing

it’s a privilege

to see the back

that’s where things happen (p. 40)

Another recurring idea is the importance of valuing the past, appreciating the old:

If I go

to see an exhibition

at a museum

and everything’s fresh and intact

I might just as well go

to Ikea

At the same time, there is something humorous about the level of detail, and the matter-of-fact way it’s narrated. As a reader, you learn all kinds of things. One curator mentions meeting ‘the world’s leading tape curators / the ones who conserved the United States’ / constitution two women / we just talked about tape for a whole week’.

After reading Omsorgslabyrinten, it’s easy to understand how people could talk about tape for a week – and even be tempted to eavesdrop.

Omsorgslabyrinten

Albert Bonniers förlag, 2023

175 pages

Foreign Rights: Hanna Bäärnhielm, Albert Bonniers förlag

Ida Börjel is a poet and translator, who has (co)translated authors such as Maria Stepanova, Lyuba Yakimchuk and Yulia Tsimafeyeva into Swedish, sometimes working together with Nils Håkanson. Her debut, Sond, won both the Catapult Prize and the Borås Tidning Debutant Prize. Her fourth collection, Ma, was reviewed in SBR 2014:1.