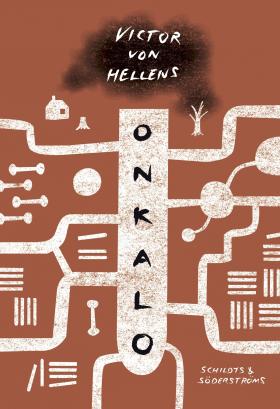

Onkalo

(Onkalo)

by Victor von Hellens

reviewed by Joanna Flower

On an island off the west coast of Finland, a vast pit is currently under construction to become the world’s first long-term repository for nuclear waste. It is expected that this facility will be operational from the mid-2020s. Its name is Onkalo. In Finnish, ‘onkalo’ means cave or cavity.

In this slim collection, Victor von Hellens has imagined a world in around 2055, perhaps 2065 – even the voice we hear in this poetry collection, a man named Zubey, isn’t entirely sure when – in which the facility was completed in 2025. Zubey arrived in 2035, having volunteered for the job of guarding the entrance to Onkalo, and has been there ever since. He has lived a hermit-like existence, with only a cat for company, and having food and provisions dropped to him by drone, though he does not know who sends them. Zubey isn’t really sure of anything, because he has no access to information about the world outside his little compound, but we gradually come to realise that there has been some sort of apocalyptic event in which, we assume, most of humanity has been wiped out. Zubey has been spared this fate due to his reclusive occupation.

This set of prose poems follows Zubey’s thoughts in his everyday life at Onkalo, which is characterised purely by mundane sets of routines, interspersed with memories of a road trip he took across the USA just after his mother had died. Zubey frequently descends into this place, which he calls ‘my America’; a blending of reminiscences, fantasy, dream and imagination. Another voice also speaks here and there, an italicised voice that seems to provide fragments of Zubey’s life before he was Zubey, though they could equally be fragments of what is to come. In von Hellens’s Onkalo, nothing is certain, nothing is known.

On one level, this work feels like ‘Waiting For Godot’ – nothing really ‘happens’ in this collection which, despite formally being called poetry, cannot really be seen as anything other than a narrative or ‘story’. The work is permeated by a rather eerie atmosphere of nothingness and pointlessness, in particular the pointlessness of Zubey’s task as a ‘guard’ in a world apparently devoid of people.

On another level, this collection could be read as a meditation on the nature of identity and community. Zubey chose to move out of society and into this strange existence because he felt suffocated in the world of people. At one point, he looks at some illustrations of a group of Finns who moved to Brazil in the 1930s to build a new community in the rainforest. The aim was to create a town and a life there where they could live in harmony with nature, ‘[F]ar away from the modern society which could lead nowhere [….] I feel I know what it was they were searching for.’ Indeed, Zubey’s life in Onkalo is completely connected to the seasons and forest all around him. Moreover, we learn that he originally had a different name, but changed it to Zubey on arrival at Onkalo, which, in and of itself, seems a pointless thing to do, because what use is a name if you don’t have a society in which to use it? A name is inexorably linked to society, is a construct by which others know you. If there are no others, a name is not necessary, and neither are other trappings of identity. And it is with this, perhaps, that we come to von Hellens’ real preoccupation. Zubey chose to be the gatekeeper to this cave, this cavity which, you could say, holds the potential to destroy the human race. In doing so, he erased his own identity, and can only fleetingly retreat to it now and again in his mind, with his voyages into his imagination and memories of America. He has become a kind of blank canvas, utterly anonymous and reduced to an animal-like existence of routines with a cat his only society.

Reading this spare work, in which, at times, you see only a few sentences on a page, you get the feeling that the author has taken great pains to slow down his own life so absolutely, to shut out all possible external noise, that he can truly listen to his whispering voice within, that essence of the human, and that he has used the medium of this narrative style of prose poems, structured around the controversial Onkalo facility, to present his findings. In a work of 78 pages with a great deal of blank spaces, he has depicted this experience of the real ‘self’ in a highly thought-provoking, relevant and elegant way.

Onkalo

Schildts & Söderströms, Helsinki, 2022

78 pages

Foreign Rights: Martin Welander, Schildts & Söderströms

Victor von Hellens was born in 1991 and studied Economics before debuting as a Swedish-speaking Finnish poet in 2020 with his collection entitled Något i tiden håller på att ta slut (Something in Time is Running Out). He was awarded the Dancing Bear Prize for poetry for Onkalo in November 2023.