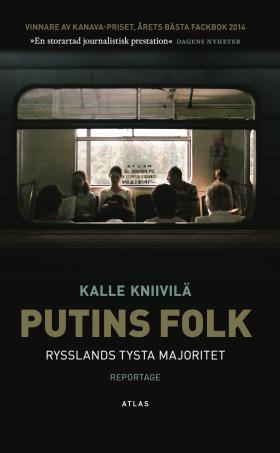

Putins folk: Rysslands tysta majoritet

(Putin's People: Russia's Silent Majority)

by Kalle Kniivilä

reviewed by Fiona Graham

‘If an alcoholic has children, they’re absolutely free to do just what they want. But decent parents bring up their children properly, so they don’t have so much freedom. We have two different parents: one called Yeltsin, the other Putin.’ These introductory words, spoken by a middle-aged welder from Nizhny Novgorod, sum up the paternalistic view of their head of state typical of many of the ordinary Russians in Kalle Kniivilä’s reportage.They also reveal that initial expectations, post-Yeltsin, were not high; one major reason for Putin’s early popularity, remarks Kniivilä drily, was ‘that the country now had a leader who could stand up straight and speak distinctly’!

While Putin has an increasingly poor image in theWest as an autocratic leader who has severely curtailed freedom of speech and who presides over a ‘mafia state’, to quote the Guardian’s Luke Harding, his approval ratings in Russia would be the envy of any Western head of state. To understand why Putin enjoys such widespread support, Kalle Kniivilä talked to ordinary people in the unglamorous Moscow suburbs and what he calls ‘Putinland’ – Cheboksary and Shumerlya in the Chuvash Republic and Nizhny Novgorod (formerly Gorky), some four hundred kilometres east of the capital.

While Peter Pomerantsev, in his recent book Nothing isTrue and Everything is Possible, illuminates the ‘doublethink’ of the sophisticated, sceptical Moscow in-crowd, Kniivilä focuses on less privileged people: factory workers, secretaries, teachers, care workers, librarians, pensioners and so on. Many of them take what they see on state-run television at face value. Some true Putin fans, like preschool teacher Irina, wax lyrical about the president’s clean living and authoritative style. However, the reason most often cited for approval is the thriving economy – which, as Kniivilä points out, is mainly the result of high oil prices on the world market.

‘Stability’, the other mantra, is vitally important to a people who lived through the chaos following the end of the Soviet Union. During the 1990s, state assets were acquired for a song by kleptocrats, while millions lost their jobs and life expectancy fell drastically. Small wonder that many Russians, associating the new ‘democracy’ primarily with plummeting living standards and omnipresent corruption, spoke of ‘dermokratiya’ (‘crap government’). Kniivilä’s portrait of provincial Russia is engaging. He gives a voice to the ‘silent majority’, who speak of their everyday activities and pleasures – being able to run an adequately funded library at last, working in an automotive plant, growing and preserving vegetables out at the new dacha. While empathising with his interlocutors – some of them friends or former neighbours – Kniivilä nonetheless asks them probing questions about their attitudes to the powers that be. The very ordinariness of their preoccupations is instructive. State employees are contented because their salaries have risen consistently over the last few years. Thanks to improved living standards and state grants, young couples now have enough confidence in the future to start a family – not a given in the chaotic 1990s. Few people are overly concerned about freedom of expression or human rights. Who’d have thought it? Ordinary Russians are very much like their Western counterparts!

Putins folk: Ryssland tysta majoritet

Atlas, 2014. 253 pages.