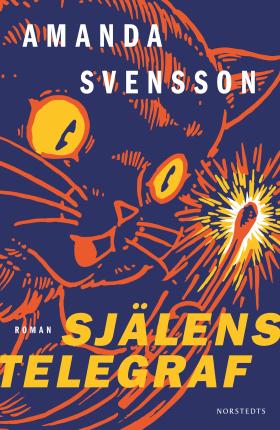

Själens telegraf

(Soul’s Telegraph)

by Amanda Svensson

reviewed by Kathy Saranpa

Iris Watkins spends her childhood in an idyllic setting in Somerset: a rambling old house surrounded by a lush garden across the street from an apple orchard that’s part of the property. Her next-door neighbour is a gruff but kind stonecutter who doesn’t seem to mind her stopping by at any time – Iris has no siblings or father to keep her amused – and her mother Grace is funny, beautiful, affectionate, and creative. But the idyll reveals itself as a prison based on subterfuge: Grace has been squatting in the house (on the basis of a verbal arrangement never made official), making money to run the household through more or less questionable means, and resorting to stealing to obtain the things she cannot buy. Her creativity has a dark side that, as the stonecutter puts it, makes her ‘stretch the truth’.

For Iris, the discovery that her mother has fabricated an entire world for her – and the realization that she still won’t tell her the truth even though Iris is old enough to want it – causes a rage that leads her to set the house on fire. Iris nearly dies in the blaze but is rescued by the stonecutter. Afterwards, she’s assigned to a series of foster homes and institutions, where she seems to emulate her mother’s life by ‘stretching the truth’ and committing petty crimes. After their final fight, pre-fire, Iris never sees her mother again; Grace, who had left Iris alone for several weeks and was thus deemed an unsuitable parent, dies of cancer a few years after the conflagration.

During her teenage years and on the advice of her therapist, Iris learns to play the cello. As it turns out, she is a talented musician. She moves to Glasgow, where she studies art, and at a party she meets Rupert, an aspiring composer. He convinces her to join his project: a band named Soul’s Telegraph that plays his compositions. Rupert proves to be the opposite of her mother. He’s honest and selfless, he believes in people’s innate goodness, and he respects Iris, seeing something special within her. They fall in love, and Iris finally has what she has always longed for, a family, although in this case, it’s a rag-tag one at best, consisting of Rupert and the various scruffy members of the band. Iris is also not entirely comfortable with her ‘siblings’ – she will not tell them about her past. Or at least not a true version of it.

Nevertheless, this past catches up to her. She comes into contact with a man who claims to be her father, and although Iris is rather sure that her biological father is dead, she plays along. He begins to give her money every week, and the entire band-family is fed and clothed with these funds. When the band needs a large sum to rent a studio for their first recording, Iris tells her ‘father’ that she wants to purchase a gravestone for her mother. He writes a large check, which she proudly hands to Rupert.

When the ‘father’ stops by with brochures featuring various designs for a dignified memorial, wondering how much progress Iris has made on ordering it, Rupert puts two and two together and realizes that Iris has lied to get the money. He confronts her; she refuses to return the money, reasoning that the man has plenty of money and the lie was helping them to achieve the band’s goal. The two split up, Iris loses her family and she feels that she’s the apple that’s not fallen far from the tree – a metaphor directly from the orchard in Somerset.

Soul’s Telegraph is a shimmering jewel in a minor key, full of symbols that emerge repeatedly throughout the narrative and characters that are as rich as the band members are poor. With deft, quick strokes, Svensson weaves in national events during the period leading up to Black Wednesday – the pre-pubescent Iris meets a desperate banker in a pub and attempts to seduce him, a scene as heart-breaking as one can imagine – and telegraphic descriptions of night life in Glasgow during the late 1990s. The main focus throughout remains Iris, a complex, hurting and damaged woman in this dark novel plumbing the depths of maternal betrayal – and the possibility of redemption.

Själens telegraf

Norstedts, 2023

256 pages

Foreign rights: Catherine Mörk, Norstedts Agency

Amanda Svensson’s previous novel, A System So Magnificent It Is Blinding (Ett system så magnifikt att det bländar, 2019), translated into English by Nichola Smalley, received multiple Swedish awards and was longlisted for the International Booker Prize in 2023. Reviews of her previous novels featured in SBR 2014:2 and SBR 2012:1.