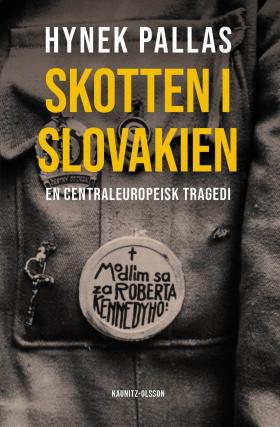

Skotten i Slovakien. En centraleuropeisk tragedi

(Shots in Slovakia: A Central European Tragedy)

by Hynek Pallas

reviewed by Fiona Graham

‘Don’t say thank you – remember.’ Slovak investigative journalist Ján Kuciak – shot dead together with his fiancée Martina Kušnírová in 2018 – would say these words whenever people thanked him for reporting on graft and mafia connections in Slovak institutions, politics and business. Mass demonstrations followed the contract killing, leading to the resignation of Prime Minister Robert Fico. Yet the protests ebbed away, while judicial proceedings have dragged on. Meanwhile, Fico has been re-elected. This raises the issue of whether Kuciak’s exhortation to remember was in vain.

Why Slovakia? Chamberlain’s notorious reference to ‘a faraway country’ and ‘people of whom we know nothing’ is probably not far wrong as regards most contemporary western Europeans’ knowledge of the Czech Republic’s ‘little brother’. Yet this small country, with its Communist and Fascist past, exemplifies many of the issues that continue to plague the nations of Central Europe, with serious implications for the continent as a whole. As such, it offers a valuable case study.

If this sounds like potentially hard going, it isn’t. Pallas deftly combines historical, cultural and political analysis with insightful accounts of his travels, including conversations with journalists, film-makers, social scientists, cultural workers and Roma people. The son of Czech dissidents forced to emigrate in the 1970s, he is also part of a family decimated by the Holocaust. This, perhaps, accounts for his passionate determination to uncover the historical truths too often brushed aside in the official narrative of Slovak history.

‘Slovakia is not a mafia state.’ When a national police chief feels he has to make such a statement, as happened after the double murder in 2018, the effect is less than convincing. Kuciak had spent years investigating tax evasion and corruption among Fico’s political associates, and had exposed links with eastern European mafia organisations, as well as with the Calabrian ‘Ndrangheta. He was repeatedly threatened by Marián Kočner, a businessman with extensive links to organised crime, coupled with influence over the police, the justice system and politicians. Though the hitmen have now been jailed, Kočner remains free.

After the Velvet Revolution of 1989, with former dissident Václav Havel at the helm, hopes were high for a new, free Czechoslovakia. But the 1992 ‘velvet divorce’ put paid to that. Having split from the Czech Republic (generally the senior partner in the old federative state), Slovakia needed to engage in rapid nation-building. Its new constitution made it clear that Slovakia was for Slovaks, with other groups living ‘on the territory of the Slovak Republic’, an ethnic definition of citizenship that signalled exclusion of the sizeable Hungarian-speaking and Roma minorities.

The Roma of Slovakia, accounting for some 7.5% of the population by Pallas’s reckoning, have been written out of the history of a region where they have lived since the fifteenth century. More pressingly, they experience systematic discrimination in education and jobs, and their settlements lack the most basic facilities (largely because providing running water and electricity would mean recognising these settlements as permanent). Since Roma living in such settlements do not own their own homes, they have no access to bank loans and thus little hope of ever improving their conditions. Asked whether she has any dreams, a shanty-town dweller replies: ‘A roof over our head that won’t fall in while we’re sleeping.’

The Roma are not alone in being written out of history. Pallas finds that Slovakia has failed to take an honest look at its first, inglorious period of separate nationhood: Jozef Tiso’s Fascist state, created by agreement with Hitler. Fascist Slovakia started to pass Nuremberg-style anti-Jewish laws immediately after the agreement was reached. Synagogues were set on fire. Eighty per cent of the Jewish population were murdered during this period. In fact, the Fascist state paid the Nazis to deport Slovak Jews, on condition that it could retain their property. Disturbingly, certain historical accounts written in the post-Communist period imply that Jews were persecuted for participation in the Slovak uprising of 1944, rather than for their very identity.

In Pallas’s view, the culture of remembrance in former Communist countries tends to focus on the period of Communist dictatorship, while their wartime regimes receive less attention. He detects a propensity to view the citizens of these states as mere victims, rather than as active participants. In fact, he argues, right-wing politicians have used anti-Communism as a stick to beat the Left when pushing for privatisation and the dismantling of the welfare state. In reality, Communist states could not have persisted for as long as they did without tacit accommodation by their citizens.

In examining organised crime, nationalism, populism, right-wing demagoguery, exclusion of minorities and the legacy of dictatorships of different political hues, Pallas has brought together themes relevant to much of Central Europe, from Poland to Hungary. Western Europeans still regularly fail to understand how Central European countries tick. And this is disastrous, since the values espoused (at least in theory) by western European nations are all too often perceived in Central Europe as being imposed upon them in colonialist fashion. It is high time for westerners to acquaint themselves with Central European realities. This book is a first-rate starting point and should be of considerable interest to an English-speaking readership across the continent.

Skotten i Slovakien

Kaunitz-Olsson, 2023

309 pages (312 including references)

Foreign rights: Thomas Olsson, Kaunitz-Olsson

Hynek Pallas, born in Czechoslovakia, is a Swedish author, film expert and journalist. His other books are Oanpassbara medborgare (2016), Ex:Migrationsmemoar 1977–2018 (2018) and Grönsakshandlaren (2021).