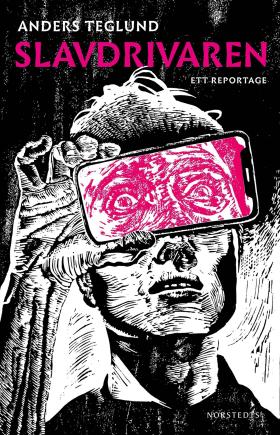

Slavdrivaren

(The Slavedriver)

by Anders Teglund

reviewed by Anna Paterson

Anders Teglund reports on barely noticed components of the gig economy: food delivery riders and their controllers. Interspersed are thoughtful essays on enslavement and surveillance through the ages. His message is an accusation and a warning: to replace whips and shackles with digital snooping does not fundamentally change the facts of enslavement.

The story begins in Dennis’s tiny flatlet, while he gets on with his job as a digital enforcer. It gives him a measure of power over others, but he doesn’t enjoy it: ‘What a fucking bore. On the job again. Another lousy day in hell.’ Not that he can’t be more articulate: ‘Life has grown so lonely, I hardly meet anyone now, because my working hours are crazy […] Just my girlfriend, when she’s home sometimes [they timeshare the flat]. And a few friends on Discord and Skype.’

Via his webcam, dual-screen gaming console and microphone, Dennis is in minute-by-minute control of the couriers – riders – who work for Foodora, a corporate food delivery company. Each rider connects to Dennis – but not to other riders – via the Foodora app. As Dennis works, Anders sits close by, watching and listening with an insider’s empathy. He once worked as a rider himself, and has written an illuminating, engaging book about it: Cykelbudet (The Bicycle Courier).

The language gets to you at once. It is unreal but functional, an app-mediated ghost speak that is neither English nor Swedish. True, English is the digital language but it has fragmented into pidgin because, typically, the riders are marginalized incomers, whose only hope of paid work is an anonymous gig job. Dennis, who understands only too well, explains: ‘They’re here because of the poverty and violence back home […] then Bolt or Uber comes along, swinging an invisible whip to make them cycle all over town in shitty weather for shitty pay.’

It is easy to relate to Dennis, a fundamentally nice man stuck in a mean job. He understands its soul-destroying potential and, before his story ends, he has left Foodora and joined the truck manufacturer Scania to do ‘real work’.

Do some slavedrivers enjoy being ruthless enforcers? Social psychology tells us that many cling to their privileges even though they are still unfree servants of their masters. Each one of the fascinating, well-read essays in Slavdrivaren examines a variant on human subjection. Arguably, the crudest, most unjust examples come from colonisers’ enslavement of natives. Except, of course, when the urge to control is an expression of the masters’ genocidal ambitions: then, any distinction between slave and slavedriver becomes sickeningly blurred, as in the case of the kapos, the concentration camp ‘functionaries’.

Within reasonably benign societies, new ideas about efficiency developed into time-and-motion methods and the repetitive tedium of piecework, later finessed by digital surveillance devices. As ‘proper jobs’ were reduced to a few set tasks – go there, pick that up, etc. – the workforce fragmented into isolated, remotely operated units and worker organisation grew increasingly difficult.

The longest essay in the book is about gig working, or Humans as a service, as Jeff Bezos, boss of Amazon, chillingly put it. Teglund focuses on the unnoticed cadres of digital platform ‘ghost workers’. This weird, sad concept fascinates him: they are people who carry out the unending ‘microtasks’ needed to weed out snags from the big software systems, from Google to Uber. The content moderators operate in the heaviest of shadows. Their work can be defined as ‘filtering the sewage flowing though digital pipes’, and, unsurprisingly, their mental health is under threat.

Can humans find ways out of digital subjection? Perhaps not. Dennis’s bid for freedom will deliver him into the AI-ruled territory of Scania’s production lines: the Robot Maintenance workshop. And what about our incisive, aware narrator? Anders Teglund, a writer and publisher, but also a musician, ends with yet another threat to individual creativity: AI-generated, non-copyrighted ghost music. Sound landscapes and ambient music are popular forms, also simply known as ‘noise’.

As he puts it: ‘The spectral intelligence advances methodically. Leaves drop, streams dry, breezes calm and songs fall silent. Surely, you’ll have heard that Spotify plans to stream literature?’

Slavdrivaren

Norstedts, Stockholm 2023

230 pages

Foreign rights: Jessica Bab, at Brave New World Agency

Anders Teglund is an author, publisher and musician. He runs Teg Publishing, which in 2021 published his acclaimed book Cykelbudet (The Bicycle Courier).