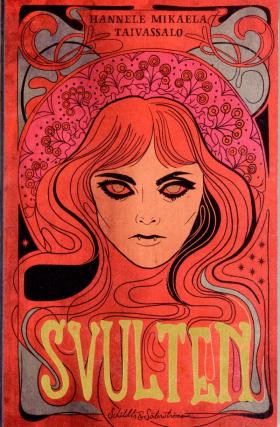

from Starved

by Hannele Mikaela Taivassalo

introduced and translated by Sarah Death

Hannele Mikaela Taivassalo’s striking main protagonist is a tall, slim woman with a fringe of jet-black hair falling over her face, red gloves, and black boots with red heels. She slips like a cat across the rooftops of Finland’s capital, hunting. She has lived for more than two centuries, growing up as tailor’s daughter Jorunn Larsdotter in eighteenth-century Stockholm, where in a time of political turmoil, illicit love blossomed between her and Baron von B.

Now, in the Helsinki of the early twenty-first century, she is the last vampire, prowling the streets of the city, driven by her hunger but with only one wish: to die. She has stilled her cravings through the years in Paris, London, Vilnius and Saint Petersburg but always been forced to move on. Only vengeance on the noble von B. family can bring her rest.

The translated extracts below are pages 34-37 and 56-58 of the novel.

from Starved

I am Jorunn. Self-Avenger. Once I was just Jorunn, someone else.

Being human, did one ever think of one’s own fragility? I cannot recall.

Do you think of your own fragility, as you rush from place to place, as if time is always short, or as you casually, carelessly board a bus one perfectly ordinary day? In your everyday life, do you remember how easily you break, expire?

I cannot recall what I thought about it. I cannot recall what human weakness was, how it felt. The extent of human imperfection, that insight only came later.

I am Jorunn. Self-Avenger.

And I am no longer as fragile as you.

Stockholm, 1789

Jorunn Larsdotter, daughter of a master tailor in the city of Stockholm, Master Laurentius, and his wife Anna Kajsa. Conditions were basic but not harsh. Always well-dressed, she and her sisters, a little too well-dressed for their rank; disapproving eyes were sometimes upon them. They were not the most beautiful, nor anywhere near the most charming, but all four of them were immodest and moved through life as though they took pleasure in it. They all thought rather well of themselves, the neighbours said later, after one of the daughters suddenly vanished and there was speculation that she had drowned herself in the river or run away into whoredom. Then she was forgotten with remarkable speed. As if nothing had happened, as if there had never been more than three daughters.

But before that: Jorunn, the second eldest, was the darkest of them all and the one who caused them the most worry. She was serious, not in the least wanton, but unconstrained and unpredictable.

They were always sewing something, the sisters, not out of interest, nor as a suitable occupation for ladies, but to provide for themselves and their family, and so they could deliver to the master tailor’s customers on time. They often tried the clothes on each other, and also helped with fittings for the tailor’s customers, re-pinning, making notes and holding things in place while the tailor measured and dictated. The master tailor was a little odd himself, surly and not overly tactful, but one of the best in town, always keeping his word and never cutting corners. The sisters’ mother was a seamstress, too, a quiet, absent-minded woman usually absorbed in her own thoughts, but always happy when she emerged from them and discovered the world about her, and her daughters.

All the beautiful fabrics that surrounded them. Glossy silks, brocades. Delicate lace and fine linen. Mother-of-pearl buttons, painted china buttons, and silver ones that looked like little bits of jewellery. The range of people coming and going. All the rumour and gossip they brought with them. Jorunn’s fingertips hardened by the sharp needle, yet still sensitive to the patterns of the fabric, the tiny stitches, almost invisible; the silence, the concentration. The laborious work and the desirable garments that they finished, whole and complete.

Lars the tailor who earned his master craftsman’s letter, Master Laurentius who was granted the freedom of the city and now had his own workshop and made clothes for the affluent burghers, among whom his family now counted themselves. The fact that the garments were daintily sewn and a perfect fit, the work never slipshod, was more important than one might think.

Many of the wealthier families of the aristocracy also entrusted their vital outward appearance to this particular master tailor.

Among them the von B. family.

These were the dog days, hot and oppressive, the air filled with the stench of rotting rubbish and incipient putrefaction. Even the light of the city was subdued and the people moved sluggishly on the streets of Stockholm. Everyone was sticky with sweat, while at the tailor’s, needles were slippery in the hot fingers holding them, and little wet patches appeared as moisture soaked into the pale silk in Jorunn’s hands.

The fabric dust made it oppressive and uncomfortable.

It was not the only thing that felt oppressive and uncomfortable in those rooms.

That Baron von B. The final fitting. It was his own suggestion that Jorunn should come if the master tailor himself happened to be unavailable. Jorunn would certainly be able to check the fit of a coat and waistcoat on her own, there was no doubt about that.

The silence settling with the dust. Nobody said anything, but the master and his wife were not happy. Jorunn had already decided that it should be so: she would go to the house of the von B. family with the coat and waistcoat, and help the Baron try on the garments, just as he asked. She had already sent word that she would come.

Silence. It was so hot. The dust was attracted to sweaty skin, dried and adhered. As if it could never be brushed off again.

Helsinki, the Present Day

Tonight, on her way downstairs, she encounters for the first time one of the other inhabitants of the house with the tower.

This little, teenage woman smells of floral perfume and recently smoked tobacco, familiar scents from an open window on a previous night; she is wearing trainers with trailing laces and loose tracksuit bottoms. Further up, a low-cut top and a hoodie hanging open, hair tied in a high ponytail, a phone and a packet of cigarettes in one hand, key in the other, about to unlock the front door of a flat. Her mascara has run, and there are other signs that she has been crying.

Behind the door that will open, the abandoned music, the same song over and over again, the voice: And I Wake up Alone.

Night. Loneliness.

But.

A movement, glimpsed out of the corner of her eye. The young woman gives a start, drops the cigarette packet.

From the gloom of the stairwell, a tall woman suddenly emerges. Very pale, with a face that seems almost to phosphoresce in the darkness. With remarkable speed she bends down to pick up the packet and holds it out to her neighbour. The girl initially throws her a quick glance, then takes a longer, sideways look as she tosses her head to flick a stray strand of hair off her cheek and takes the cigarette packet with a defiant look, eyebrows slightly raised.

Girlblood. Warm and fierce.

The tall woman takes a step closer to the door and leans against the wall beside it. Contemplates the girl.

‘You shouldn’t be out this late,’ she says slowly.

The girl looks at her, uncomprehending at first, and then says, her eyes black:

‘And what the hell has it got to do with you?’

Jorunn smiles, leans forward, puts her head on one side and regards the eyes and the dark that runs beneath them before she asks:

‘What is it making you cry like this?’

The girl stares at her with astonished eyes. Then, suddenly, as if something ruptures, as if there is a point at which nothing matters any more, her voice breaking, wounded, everything pouring out:

‘Because there’s nothing to do except die, nothing, I haven’t got anything left, and there’s nothing to do now except die! Good night.’

And she turns to unlock the door, the key shakes in her hand, scrapes in the lock; she smells more of anger than of sorrow, the girl, and when the key won’t go in first time she turns round, tears at the cigarette packet, tries to get one out. Her skin is glowing, sparkling.

This is the house with the tower; they both live here. If she, Jorunn, is to carry on doing so, nothing must happen. She has a rule these days: never anyone from her own neighbourhood. It is a very simple rule. Sometimes very hard to adhere to.

‘For your own good,’ says Jorunn, ‘go in. Lock the door. It’s night.’

‘Fuck you,’ says the girl.

She smells sweet, as if there were sugar flowing in her blood, and as if her anger were making that blood run hotter, faster. She puts the key in the lock, but before she turns it she looks back one more time at the tall woman:

‘Fuck you, I’m not scared of the night and you’ve no idea what I’ve already been through and I’ve probably seen more than you will in your whole life, so fuck you.’

Jorunn smiles again, in your whole life, she gives a low laugh of delight. But then stares straight into the young eyes and says:

‘Go. Go now. Believe me. Get in quickly. Now.’

The mouth in the young face opens and then shuts. The big eyes, ringed with messy black smears, grow even bigger. As if she could see something, as if she understood, she hastily unlocks the door, fumbles to remove the key, plunges across the threshold, into her rooms where the same song is starting all over again, and slams the door shut with her whole body weight.

Through the door, Jorunn can hear her breathing, her heart thumping under the skimpy top, a peppery smell of fresh sweat breaking through. She stands outside the door, smiling, touches its surface. Just a thin layer of wood between her and the young body. Just a thin, thin layer and yet she is still alive, the girl.

‘Fuck you,’ comes the voice one last time, stubborn if unsteady, from the other side of the door.

The tall, pallid woman laughs, and before she goes she gives the door a light, almost kindly pat.

And I wake up alone.

This is her house, with her tower. She had almost forgotten that others lived here too. Human beings.

And I wake up alone.

This is where the young creature lives. Sweet-smelling, impetuous.

Now she knows.

Now she knows it so clearly and utterly, and so hungrily that she hopes she will very soon be able to forget it again.

Svulten

Schildts & Söderströms, 2013

Rights: Mari Koli, Schildts & Söderströms

This translated extract is published with the permission of Schildts & Söderströms.

A review appears in this issue.

Sarah Death is a translator and editor.