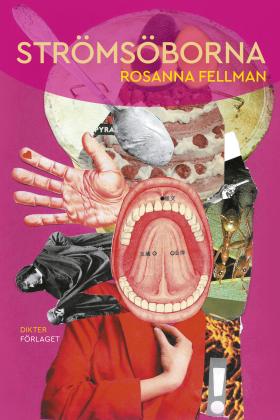

Strömsöborna

(The People of Strömsö)

by Rosanna Fellman

reviewed by Joanna Flower

The title of this collection of poetry Strömsöborna (The People of Strömsö) cannot help but recall August Strindberg’s 1887 novel of everyday life on the Stockholm archipelago, Hemsöborna (The People of Hemsö), which was inspired by summers he spent on the island of Kymmedö. The portraits he painted of the people there were not particularly flattering, and the inhabitants took such umbrage that they forbade him ever to return. Fellman’s work takes its name from a popular Finland-Swedish TV show, Strömsö, a long-running idealised lifestyle programme which provides ‘inspiration for house and home, leisure and everyday life’. ‘Strömsö’ is the name of the beautiful red and white painted villa where these activities which can guarantee you an idyllic existence take place. In Fellman’s work this version of Finland is depicted as an extremely unhappy home, with many alienated, isolated, sometimes angry, sometimes pitiful, sometimes neurotic voices. Fellman’s Finland is broken, its inhabitants flattened under the homogeneity of a globalised world, narcissistic, incapable of connecting with the human beings around them. But times have certainly changed, for, rather than being chased out of town, as Strindberg was, Fellman has instead been praised across Finnish media and awarded the 2019 Finnish Culture Prize.

Fellman dips into the heads of a broad array of people living in Finland today, depicting how daily lives are led under the tyranny of mobile phone calendars; the loss of identity that can come with motherhood; experiences of the ‘snowflake’ generation, obsessed with their online identity and how they appear; old men on buses who cannot understand a word that comes out of the mouths of today’s ‘pubescent animals’; alcoholics; desperate lonely people using dating apps for casual sex to fill in the gaping voids in their lives; volunteers in racist organisations – there is no doubt that it is a devastatingly dark picture that Fellman paints of the society around her.

One theme that recurs is that of lack of empathy and compassion and people’s sheer inability to deal with other’s traumatic experiences. The collection opens with ‘Dad Hit Me’, and depicts, from the child’s point of view, a mother refusing to face her husband’s abuse towards their child, who later ends up in care. In ‘The Mantle’, on telling her mother she had been raped, the narrator is simply told: ‘Silence is golden’. In ‘Bessie’, the narrator fears the police accessing his/her search history and talks of furtive trips to a brothel and secret meetings with what turns out to be a golden retriever. The narrator is so utterly alienated from the world that these physical sessions of embracing a dog are the only form of physical closeness, warmth and real contact available, and they become fetishized and obsessed over.

Life in a capitalist world with its rampant and meaningless consumerism is highlighted in ‘The Commandments’, in which the narrator talks about the freedom of life in Finland in the 1980s, with all its opportunities, and how great that was: ‘Being able to get stuff for the money I’ve earned is probably the only habit I have left’. This is followed by a great list of all the things ‘we need’ now, a list that multiplies and builds upon itself to absurdity. This, it would seem, is the heart of the work – the gap between what could have been, with the freedom released to Finland with the collapse of the Soviet empire on the one hand, and, on the other, the capitalist American-dominated world of today, which Fellman sees as so pernicious. The Strömsö of this collection is as empty and artificial as a TV programme.

Fellman writes in Swedish, with a fair amount of Finnish sprinkled here and there, which provides spice and exoticism for the Swedish-language reader and roots it in a very clear sense of place. At the same time, the language of globalisation is scattered throughout – Facebook, Babybjörn, Coca Cola – and so it also has a universal appeal.

It may not be Strindberg, but undoubtedly, Strömsöborna makes for an interesting, and in some cases, entertaining read, and provides an important snapshot of Finland-Swedish society today. The project is clearly ambitious and at times very well-executed, yet the reader is left with a lingering feeling of frustration that Fellman has not, say, delved more deeply into some of these topics, perhaps gone further to depict more in-depth the psychologies of fewer characters, rather than trying to cast her net so wide that it sometimes feels like a dizzying experience of head-hopping as superficial as some of the experiences she seeks to depict. But perhaps that is exactly the point.

Strömsöborna

Förlaget, Finland, 2019.

325 pages.

Foreign rights: The author holds the rights to the work, and can be contacted via the publisher.

Rosanna Fellman is a Swedish-speaking Finnish stage poet and activist. She was awarded the Finnish Culture Prize Vimma for Strömsöborna in 2019. Her second collection, Republikens president – Tasavallan presidentti (President of the Republic) was published in 2022.