‘There’s nothing like the act of translation to reveal the magic of how and why a piece of writing gets under your skin’

Translator and author Saskia Vogel on her Bernard-Shaw-Prize-winning translation of Johanne Lykke Holm’s Strega (Lolli Editions, 2022)

interviewed by Alex Fleming

Awarded biennially by the UK Society of Authors, the Bernard Shaw Prize recognises outstanding translations into English of full-length Swedish-language works. In February 2024, Saskia Vogel was announced the winner of the 2023 award, for her translation of Johanne Lykke Holm’s Strega. The judges, who included translator Nichola Smalley, author Amanda Svensson and Guardian journalist and former news editor at The Bookseller Alison Flood, offered the following praise for the translation:

‘Johanne Lykke Holm’s story of a girl who arrives to work in an empty hotel in a remote Alpine town is deep and dreamlike, hinting at and then revealing the dark underbelly of growing up as a young woman in a violent society. Saskia Vogel matches the mythlike flavour of Holm’s tale in her luminous translation of this eerie, disturbing novel.’

In this interview with SBR, Saskia sheds light on the process of bringing Strega into English, including unexpected ways to nurture the uncanny in a text, and how translation can stretch the limits of the English language.

SBR: Congratulations on being awarded the Bernard Shaw Prize! I’m going to start my questions at the beginning: What first drew you to Strega? Which facets of your translation (and writing) practice do you feel it spoke to, and did this change at all over the course of your translation?

Saskia Vogel: Oh, thank you, Alex! I’ve been a fan of Johanne’s work ever since Johanna Haegerström at Bonniers suggested I might like it. I translated a little of her first novel for Two Lines Journal, and was totally in love with her style, her world-building, the occult, horror, and esoteric strands alongside the politics of the Young Girl. I hotly anticipated Strega, and it was everything I could hope for. I’m interested as a writer and translator in the themes in Strega as well as the exploration of style. As always, there’s nothing like the act of translation to reveal the magic of how and why a piece of writing gets under your skin. I think my experience of the text while translating was pretty consistent, developing mostly around aesthetic questions. I felt very at home in this world and language.

In their prize motivation, the judges allude to Strega’s dreamlike, uncanny and mythlike qualities, and the novel is full of surprising, sensory imagery. How did you navigate and nurture this element of the uncanny in your translation?

Making language strange, but at first glance simple and straightforward was a big challenge. Two things come to mind. One, I read an article (Medium, link paywalled) about a data science analysis of Macbeth. What is the creepiest word in Macbeth, they asked? What makes the language so eerie and unsettling? What makes the experience of reading it feel a little off? The analysis showed that this effect lay in the usage of the word ‘the’. What changes when you use the definite article, or leave it out: the owl (the one we all know), owl (some sort of mass of owl). Or think about how David Attenborough uses, like, a singular noun to describe plural animals (I’m sure there’s a term for this...). I thought about these two things a lot in terms of setting the reading experience askew. I was also so glad to already have a dialogue with Johanne in place, which meant when I spontaneously asked her how the text should feel, what kind of fabric, she said ‘polyester’ and then we talked about that feeling of your teeth getting furry when you’ve had too many sweets, the way it makes your tongue feel, the thirst. I held that in mind.

...when I spontaneously asked [Johanne] how the text should feel, what kind of fabric, she said ‘polyester’ and then we talked about that feeling of your teeth getting furry when you’ve had too many sweets, the way it makes your tongue feel, the thirst. I held that in mind.

In Strega, Johanne Lykke Holm makes use of a precise, purposeful prose; in interviews (such as Not Faking Utopia by Ann Kathrin Doerig[1]) she has spoken about how this is intended to speak to and subvert the systems of control that are placed upon women and girls. How did you go about finding the text’s rhythms and resonances in English?

This is a great question and really tricky to answer! The short answer would be that I followed the Swedish as closely as I could, and for this text it was really important, down to sentence structure and word order. Kira Josefsson is a translator whose thinking around translation pushes me to stretch the limits of the English language, and in Strega, there was a delicate balancing act. The editors were wonderful and really open to having a dialogue about the process, so I did a very literal first draft that they commented on. I wanted it to be strange and retain the strangeness it has in Swedish... without veering into Swinglish... they kept me in check and kept an eye out where my knowledge and familiarity with the sensibilities of Swedish prose style created certain blindspots for me, especially after reading the book so many times. And then there’s the part of translating that has become mysterious to me: the sense I have of things as I move quickly through the text and am sure that this sounds better than that.

A sense of ritual is embedded in the book – primarily in the repetitive nature of the girls’ everyday work, but also in how they respond to the disappearance of one of their group. Do you have any translation ‘rituals’, or does every book call for a different approach?

I don’t really have rituals in writing or translation, other than ritual discipline. I pursued this work in part because Sarah Death mentioned that it’s possible to do around a parenting schedule, and I’ve found that to be true. And as a parent of a child born during the pandemic, finding time can sometimes be the hardest part. Like right now, I’m doing punishingly early mornings, waking around 4 or 5 to write, so my work day is for work; it’s actually feeling pretty good. I do have a process that’s familiar to me. Fast first draft, followed by draft upon draft, each subsequent draft addressing a different layer of the text.

Finally, you and Johanne Lykke Holm have collaborated in quite a special way, in that you have both translated one another’s work[2]. Do you feel that this symbiosis in your working relationship – and knowledge of one another’s crafts – affected your translations in any way?

I feel really lucky to have worked with Johanne in these ways. I think it built trust. And when she translated Permission, I felt like she’d have an eye for certain aspects of the text that were particularly meaningful to me, but that could be overlooked? An esoteric riff on girlhood, womanhood and Britney Spears (unnamed), for example.

Footnotes

- [1] Not Faking Utopia is a film portrait of Johanne Lykke Holm produced by Ann Kathrin Doerig. The film can be found at the bottom of the book page on Lolli Editions' website: https://www.lollieditions.com/books/strega

- [2] Johanne Lykke Holm translated Saskia Vogel’s novel Permission into Swedish (Mondial, 2019).

The Bernard Shaw Prize 2023

Winner:

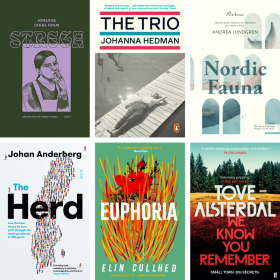

Saskia Vogel for a translation of Strega by Johanne Lykke Holm (Lolli Editions)

‘Saskia Vogel’s translation of this astonishing novel is truly virtuosic – the text comes alive in all its uncanny beauty as the English language is made to bend supply and excitingly without ever losing its elasticity.’ – Nichola Smalley

Runner-up:

Jennifer Hayashida for a translation of Euphoria by Elin Cullhed (Canongate Books)

‘Transforming Cullhed’s voice – strongly influenced by Plath, yet still uniquely her own – cannot have been an easy feat for translator Jennifer Hayashida, but she does it so brilliantly.’ – Amanda Svensson

Shortlist:

Kira Josefsson for a translation of The Trio by Johanna Hedman (Hamish Hamilton)

John Litell for a translation of Nordic Fauna by Andrea Lundgren (Peirene Press)

Alice Menzies for a translation of We Know You Remember by Tove Alsterdal (Faber and Faber)

Alice E. Olsson for a translation of The Herd by Johan Anderberg (Scribe UK)

Strega

Lolli Editions, 2022, 183 Pages

Winner of the 2023 Bernard Shaw Prize

Winner of an English PEN Award

Johanne Lykke Holm is an author and translator. Nominated for both the Nordic Council Literature Prize and the European Union Prize for Literature, she is establishing herself among the most promising up-and-coming literary authors in Sweden. She has also translated Yahya Hassan, Josefine Klougart, and Hiromi Itō into Swedish.

Saskia Vogel is an author, translator, and the deputy editor of the Erotic Review. She was a 2021 PEN Translation Prize finalist and Princeton University’s Fall 2022 Translator in Residence. Her debut novel, Permission, was published in five languages, and she was awarded the 2021 Berlin Senate Grant for Non-German language Literature for her writing. Born and raised in Los Angeles, she now lives in Berlin.