An Accidental Translator

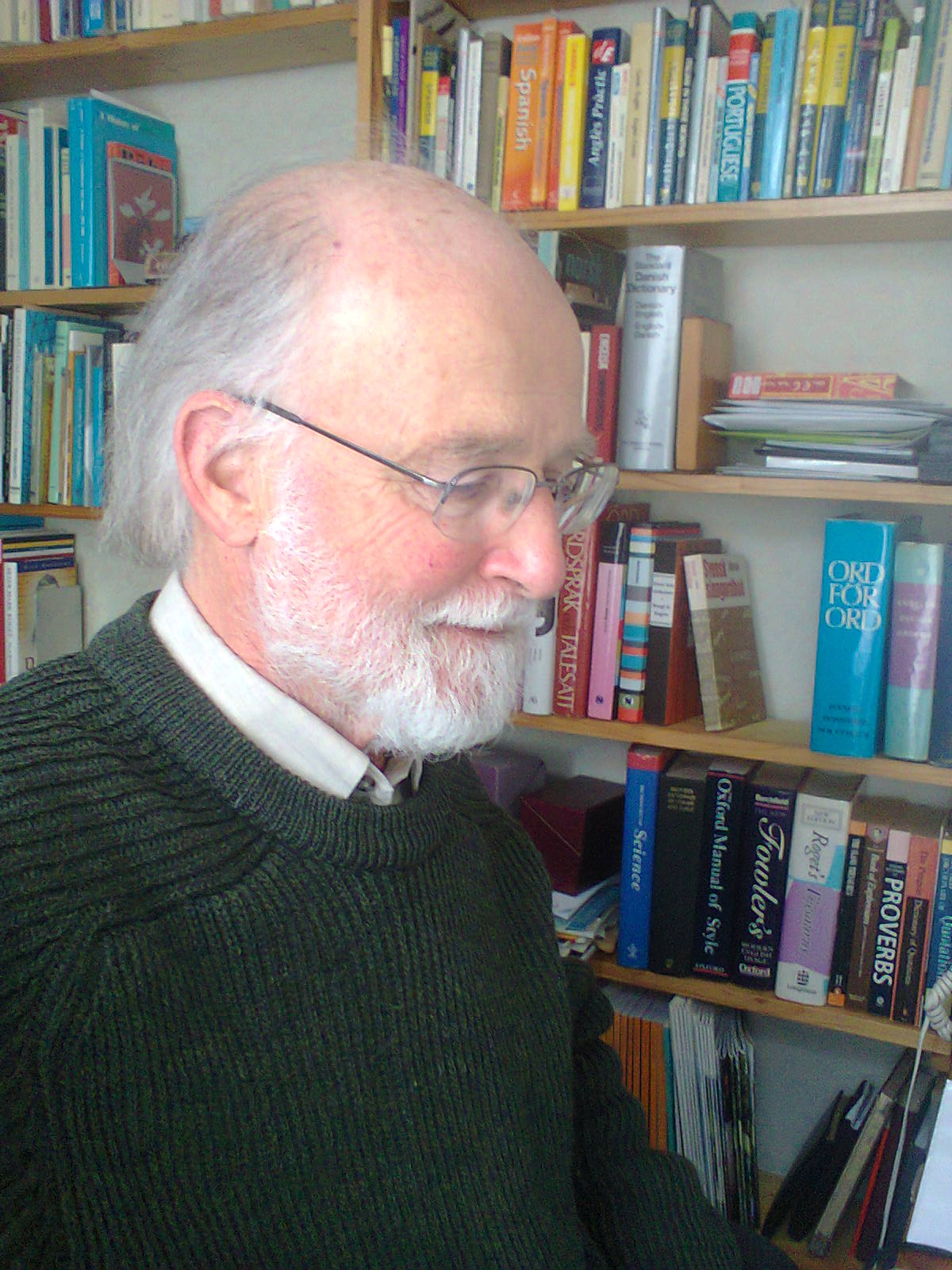

An interview with Tom Geddes

by Deborah Bragan-Turner

At its annual ceremonial meeting on 20 December 2019, the Swedish Academy announced that it was awarding two prizes for the promotion of Swedish literature abroad: to Tom Geddes and to Professor Klaus Müller-Wille of the University of Zurich.

Tom Geddes was the founding secretary-treasurer of SELTA and for some years also its chair. At the end of 2019 he stood down from 36 years on the editorial board of Swedish Book Review. He won the inaugural Bernard Shaw Prize for Swedish Translation in 1991 and was awarded a Swedish Academy translation prize in 2002. He also received the Royal Order of the Polar Star in 1992, with Joan Tate and Laurie Thompson, and was elevated to Commander of the same order in 2006, an honour he regards as much as an accolade to SELTA for its 25th anniversary as to himself.

Q: What first sparked your interest in the study of languages and literature?

Having left home and school in Norwich at 18 in 1962 with A-levels in French and German, but a rather dissolute and anti-academic attitude, to seek my fortune in London, it was four years and four jobs later (and an early marriage which has so far lasted 55 years) that I went to university. Without any real sense of intellectual direction, I felt my only chance of acceptance was to resume study of my favoured language, German, a preference engendered partly by the (to me) inappropriate selection of French books at A-level and partly by the experience of hitch-hiking and hostelling holidays in the two countries. All English universities required a minor subject for language majors, which led me to the fairly uninformed choice of a subsidiary in another Germanic language.

Q: And why Swedish in particular?

My selection of Swedish was probably stimulated by the films of Ingmar Bergman, bringing to me and many others a new experience of cinema in the early sixties. At University College London, subsidiary Swedish was a mere two-year course, the first year language and the second combining books for detailed study with a rather superficial survey of literature from the 18th century to the present. After an intercalated third year in Germany with a semester each at the universities of Frankfurt and Freiburg, and then a final year of German studies in London, I knew that my real desire in life was to remain a perpetual student! In those days tuition fees and maintenance for undergraduate courses were fully funded by local government, and for postgraduate studies by central government. I successfully applied for a grant to embark on a PhD and simultaneously a Swedish Institute scholarship for a year. I compromised with an initial six months at Uppsala University, enhancing my knowledge of Swedish, Sweden and its literature and changing my initial choice of thesis topic from a comparison of Strindberg and Kafka to the broader field of the diary-novel in German and Swedish literature.

Q: Did you have any sense of embarking on a career?

I suppose an ultimate aim at that stage would seem an academic career, but that really only came to mind gradually as I sat alongside other postgraduate students in the cosy Institute of Germanic Studies library then in its Georgian terrace on Russell Square in London. While others were indeed finding university posts in German from time to time, my thoughts were focused on the three years of research that lay ahead of me. Then came the clinching chance that pushed me more towards Swedish than German: a three-year contract to teach Swedish and German at the University College of Wales in Aberystwyth. It was the first year of honours-level Swedish there, and I had the privilege of devising the syllabus alongside Laurie Thompson. I was able to indulge my own interests in 20th-century prose and drama while he specialised more in the 18-19th centuries and poetry – but given my relatively meagre background in Swedish I was also teaching myself as I went along!

Q: How did your post in Aberystwyth develop?

My time was spent primarily on Swedish literature, with beginners' language teaching in Swedish (we had a Swedish lektor and my more experienced colleague for advanced levels). The German side of my required duties was language only, though I volunteered a short course on the novels of Max Frisch, which I always thought a deeper existentialist exploration of the human condition than the plays; and I was even cajoled into the hubristic venture of directing one of Frisch's lesser known plays performed by the students in German at the local theatre, with simultaneous translation through audience earpieces. Other extra-curricular activities for the students included Bellman evenings, where I was better as a DJ than as a singer. I would have loved a permanent post in Aberystwyth, but the three-year contract was not extendable.

Q: So you became more of a Swedish specialist?

Swedish got me my next job! The British Library, then still in the British Museum though administratively separated from it, advertised for a Scandinavian specialist, ‘librarianship qualifications an advantage’. The lack of requirement in this respect was certainly an advantage for me! But far from specialising, the post pushed me further into the dilettantism which is probably my natural inclination. I had to select and deal with books on all subjects from all the Nordic countries, which meant learning the rudiments of Finnish, guessing my way through Icelandic, and finding out more about the other countries, their intellectual histories, the world of antiquarian and modern books and publishing. My thesis, having made little progress at Aberystwyth, slowed still further, though I produced two minor spin-offs: a short monograph and later a broader book-chapter on Hjalmar Söderberg. It was probably translation that brought it to a final halt, compounded by the addition of German responsibilities and an increasing managerial role within the Library.

Q: How did you become a translator?

Though the term ‘networking’ was not current at the time, my first commission came through an elderly translator, Mary Sandbach, who had formed an intuitive belief in my potential from a few encounters at academic Scandinavian conferences, where we were both on the periphery. She no longer wished to take on full-length novels, and recommended me to the Bodley Head when they offered her Bo Beskow's Och vattnet stod på jorden (my obvious working title ‘The Waters Prevailed Upon the Earth’ was rejected by the publishers in favour of the much sexier Two by Two - a ploy which failed, since the book had little success in Britain; they commissioned reports from me on his subsequent books, but published no more). The date of that first translation was 1980, and although I then undertook the translation of the autobiography of an eminent educationalist (Torsten Husén: An Incurable Academic, 1983), a decade was to pass before I got my next literary translation – and my stalled part-time career was relaunched by the same Mary Sandbach. She had been offered Torgny Lindgren, worked on his short stories, but recommended me for his first novel to be translated, Bathsheba (1988). In my tribute to Mary Sandbach after her death I described translation as ‘an active relationship with Swedish literature which lent itself to intermittent pursuit’. I was quite pleased with the formulation at the time, meaning it as a contrast to research, but it occurs to me now that ‘intermittent pursuit’ applies not just to part-time writing based on a given text or varied individual projects without long-term commitment, but also to the vagaries of the freelance life, where there may be significant gaps between commissions.

Q: How would you advise others to start?

This has never been an easy question to answer. The skill needed, of course, is a fluent and imaginative command of your own (the target) language, together with a knowledge of the culture and idiom of the source language. A study of translation theory can make one more alert to pitfalls and techniques, but may not necessarily make a good translator, nor open doors to commissions. Pitching a book to a publisher, with a brief synopsis, evaluation and short sample translation, may very occasionally strike lucky, but begs the question of whether publishers are able to trust your judgement even if they like your writing. A series of rejections may be time-consuming and demoralising. An approach to the publishers of the original book can be of mutual benefit, but they too will be wary of an unknown translator possibly ruining a book's chances rather than helping to place it. Taking on any and every short translation that might come your way can help build up a ‘portfolio’ to prove your abilities, including contributions to little magazines, on-line outlets, or subcontracting for commercial or non-literary material where others are overloaded. To that end, joining translators' associations can lead to useful contacts who may provide advice, encouragement and opportunities rather than competition. But I would usually recommend looking for a congenial career or guaranteed employment in another or related sphere while trying to establish oneself as a literary translator.

Q: You have received a number of prestigious awards, most recently from the Swedish Academy. How do you feel about those?

When I received the first Bernard Shaw Prize in 1991 I had been the pivotal person negotiating on behalf of SELTA with the Swedish Institute, the Swedish Publishers' Association, the Anglo-Swedish Literary Foundation and the Society of Authors for funding and practical support to set it up. It was thus somewhat embarrassing that one of my translations of Torgny Lindgren was selected from the foregoing ten-year period for the prize. And the language and style were hardly my forte: The Way of a Serpent was a very biblical novel linguistically, if not in the same way as Bathsheba, my first Lindgren, and I am a totally non-religious person. In this, as in all my translations, I benefited enormously from having my wife Carol as my primary editor. Although like me an atheist, her knowledge of the Bible and feel for the language saved me from missing allusions that had not already sent me to our bookshelves for a Concordance. And the latest Swedish Academy award, for the promotion (introduktion) of Swedish literature, fills me with guilt for having more or less withdrawn from translation and publishers' reports over the last eight years since a heart attack in 2012.

Q: And has there been a highlight?

As for highlights: I am not a royalist, but it cannot be often that a translator may speak to a king! Each of my two royal orders was presented in London by the Ambassador of the time, on behalf of the King, but in 2007 I was guest speaker at a launch event at Drottningholm Palace for the Linnaeus Apostles project, where I gave a talk on my translation from the 18th-century German of Johan Peter Falk's expedition through little-known Russian lands, Essays on the Topography of the Russian Empire (written by one of his German students after Falk himself had committed suicide in Kazan). Although we all stood when the King and Queen formally entered the Rikssal, there was also wonderful informality: as we mingled beforehand, the King passed through the room, indicating with a gesture that we should ignore his presence; and he joined us for drinks and canapés afterwards. This event received royal support because of Linnaeus (and maybe because ex-prime minister Ingvar Carlsson was involved with the project). But I think the main thing to say about all the above occasions is that they are a measure of the recognition Sweden gives to translators as mediators and ambassadors of their culture.

Q: What do you see as the key to a successful translation?

If by successful we mean a book that sells, we have to acknowledge that a publisher often dares take more liberties with a title than a translator would venture. I've mentioned the Bodley Head's Two by Two; other examples among so very many could be the pithy Manrape for the literal ‘Men Can't be Raped’ (Märta Tikkanen), or the intriguing The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo for the rather turgid ‘Men Who Hate Women’ (Stieg Larsson). For the quality of the translation itself, one of the hazards for a translator is the close affinity between Swedish and English. We use the term ‘false friends’ for words that seem alike but have different meanings, but the whole Swedish language can be a dangerous friend, in that its simplified grammar and Germanic vocabulary are so akin to English that it is easy for a translator to fall into a too-literal rendering which sounds almost idiomatic yet is nevertheless slightly ‘Swenglish’.

Q: How do we avoid falling into this trap?

With a highly inflected and grammatically complex language such as German, one is aware of the need to restructure entire sentences into English, and the vocabulary, while consisting of basic Germanic elements, creates complex compounds which push the translator's mind towards a more sophisticated word from the Latinate heritage of English. Our richness of near-synonyms from our dual Germanic and Latin bases means that we have a more nuanced register in English, so a straightforward translation from Swedish can so easily sound banal unless the appropriate register is found. Likewise too close a rendering of recurring words or concepts in Swedish texts can sound too repetitive in English just because we have more near-synonyms available. One has to balance the author's resonances against the readability and impact of the book on the target-language reader.

Q: Have you had any particular disappointments, and are there any authors or books you hope one day will be translated?

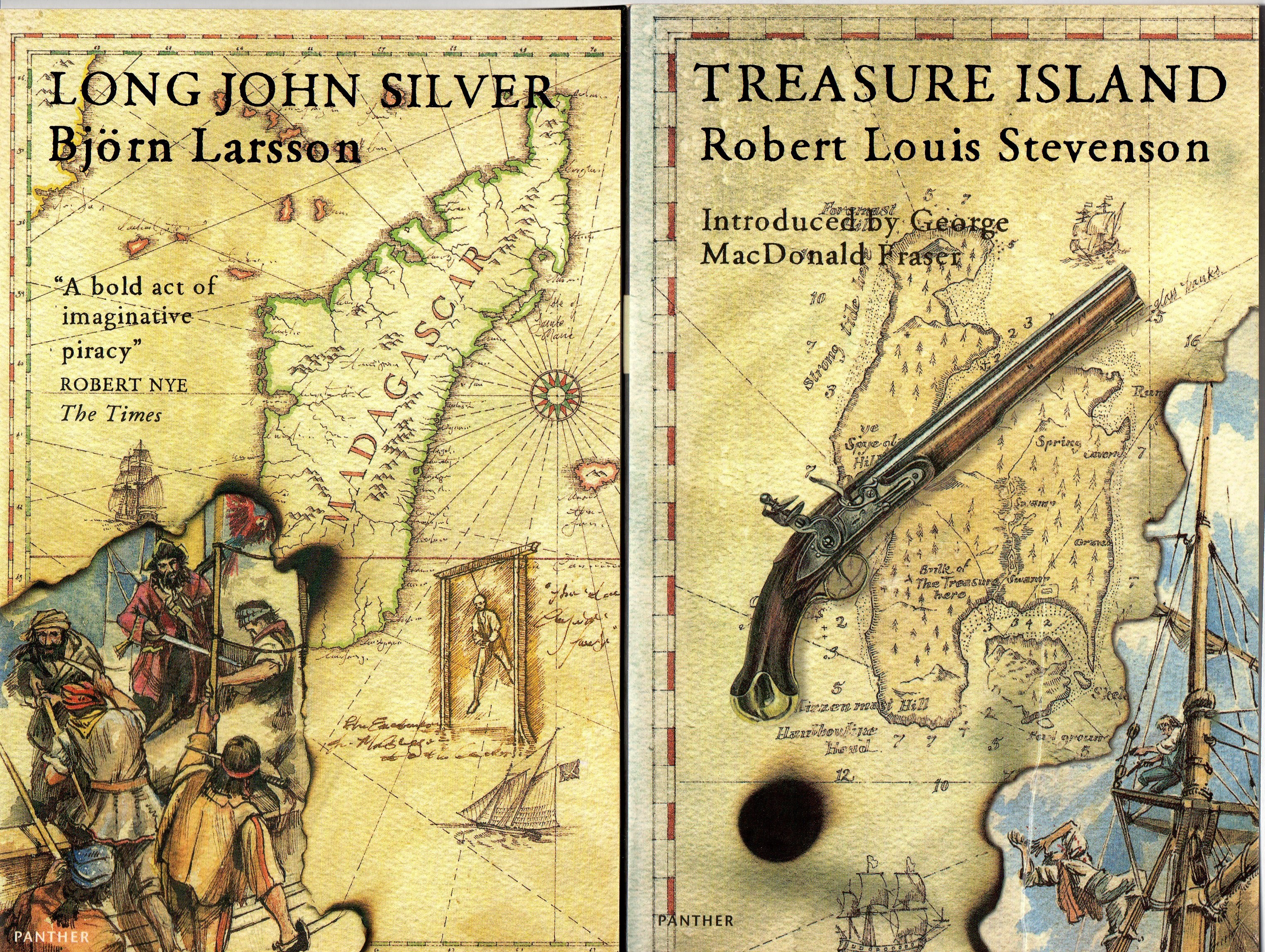

One real disappointment was that my best-ever translation, Björn Larsson's Long John Silver, did not receive the recognition or sales it deserved – though the reviews were excellent. So I can say to those who have not (yet) won prizes that lack of recognition does not necessarily indicate any lack of merit! When perusing the list of the more than a hundred books on which I have written reports for publishers, another disappointment that still stands out for me is Carl-Henning Wijkmark's Dressinen (The Trolley, 1982), a philosophical rumination and adventure story of a voyage across the Atlantic with three apes on a converted railway trolley. It preceded by two decades, and in many ways surpassed, Yann Martel's hugely successful similar conceit Life of Pi. French and German publishers took the Wijkmark, which may be a reflection of different tastes in fiction in Europe. A couple of general points also strike me: of all my commissioned reports, fewer than 20% led to a translation, at least by the specific publishing house. Admittedly some of my judgements were negative, some damning with faint praise; and some of the books were eventually taken by other publishers. It was always sad to see worthy books rejected after a positive report, but personally disquieting to read subsequent good press reviews of published translations of books that may originally have been rejected as a result of a half-hearted report by me!

Q: The theme of our current issue is emerging voices. When you began translating in 1979, whose were the new voices then?

My overall impression is that younger writers then were hardly ‘emerging’ from Sweden at all. Names that were becoming known abroad tended to be those already well established in Sweden, such as Sven Delblanc, P O Enquist, P C Jersild, Torgny Lindgren. This may have been due to a combination of factors: English-language publishers were not actively seeking new writers from Scandinavia; it was less of a risk for them to take a writer who already had other books to follow on if a first translation were successful; the work of new writers was felt to be less mature than what might follow; Swedish publishers were not pushing sales of foreign rights very hard; and there was less support for younger writers: this came later from initiatives such as the Swedish Institute's (now Swedish Arts Council's) New Swedish Books and our own Swedish Book Review. The inception of the Gothenburg Book Fair in 1985 also provided a forum for new writers, and the Swedish and Nordic presentation of new writers at the London Book Fair after it expanded from its modest 1971 beginnings has had an impact more specific than the bigger market of the Frankfurt Book Fair.

Q: What changes have you seen in Swedish publishing since you began translating? And in British publishing?

In Sweden it has been mainly the arrival of agents and the more active pursuit of the sales of foreign rights. When we started SELTA in the early eighties it was really only Bonniers and Norstedts who had dedicated foreign rights staff, a single individual each and one of them only part-time. Foreign rights departments subsequently evolved into separate agencies, some hived off from the parent publisher and others set up independently. This trend has coincided with the surge in British publishers' interest in Swedish, Scandinavian and all foreign fiction.

In Britain the demise or takeover of many of the traditional publishing houses has been regrettable, though some imprint names have been retained or reintroduced in the big conglomerates. Smaller publishers were often more open to translations, perhaps because they were able to indulge personal tastes or ignore corporate accountants. Marion Boyars and Peter Owen are two examples that come to mind. But on the other hand, current independents like Bloomsbury or Granta or big conglomerates like Random House and its subsidiary imprints seem to have maintained or even increased their output of translations. And the vicissitudes in the evolution of MacLehose Press are a prime example of riding the waves of the turbulent seas of British publishing.

Q: Interest in Swedish literature abroad has grown substantially over the last few decades. Is this solely due to the popularity of Nordic Noir?

I think the simple answer is yes, but with some qualifications. Crime fiction has always been a big-selling genre in Britain, although the review pages of the press usually give more attention to general fiction. Interestingly, crime tends now to be seen by publishers almost as two sub-genres, popular crime and literary crime. The latter can more easily make a bridge, for publishers as well as the book-buying public, to literary fiction rather than remaining a separate category. Even the middle-market press now tends to distinguish between general fiction and literary fiction, so while the space devoted to reviewing has diminished over recent years, the sophistication of both reviewers and readers may have increased. The ‘modern breakthrough’ for Nordic fiction really began with Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow, a Danish novel published in a pseudonymous English translation in 1993. Its plot of amateur detection may not have categorised it immediately as crime fiction, so its crossover nature also lent more impetus to general Scandinavian fiction. Its immense success may have been partly engendered by the ubiquitous addition of its handsome author's photograph to reviews, unusual for an unknown writer, and partly to the plethora of novels then being published with some aspect of snow in their titles. It was followed in 1995 by the English translation of the Norwegian Sophie's World, a novelistic history of philosophy for adolescents, which also became an instant bestseller. Sweden caught up only much later, in 2008, with Stieg Larsson's The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, coincidentally also a pseudonymous translation, which soon surpassed its Danish and Norwegian precursors in sales, in worldwide translations, in sequel volumes, in translated author biographies, and in cinema and TV adaptations. These three authors, Høeg, Gaarder and Larsson, gave a fresh aura of success to Scandinavian fiction as a concept, from which Swedish books have continued to benefit. British and other foreign publishers are more open to new authors, and the lesser known Nordic countries, Finland and Iceland, have also enjoyed an increase in titles published in translation. Each individual Nordic country has benefited from association in the public mind with its neighbours. And the seemingly endless number of Scandinavian and other foreign TV crime serials on British TV is keeping this public interest alive.

Q: You founded SELTA in 1981 and you were its chair for a number of years. Membership has continued to grow and the association’s activities have expanded. What, in your view, has helped it thrive?

It has been a combination of individual initiatives and commitments, support from Sweden, and mutual encouragement. There was little sense of community among translators of Swedish until the late 1970s when the then Swedish cultural attaché in London, Ove Svensson, brought together a small number of translators. I was among the invitees because I had been commissioned by the Embassy to compile a bibliography of English translations from Swedish and books on Sweden in English. He and his successor Terry Carlbom went on to organise two larger conferences of translators before the latter encouraged us to form our own association. Our two most experienced translators were Patricia Crampton and Joan Tate. They represented opposite ends of a spectrum. Patricia had long been a highly active member of the Translators Association of the Society of Authors, campaigning for rights and standards both nationally and internationally. Joan was a lone writer-translator who had never met fellow-translators before. But both had an involvement in the world of publishing that gave me the confidence to volunteer myself to run the association as its secretary-treasurer with the back-up of their knowledge and experience. And we have to admit, with much gratitude, that SELTA has benefited from the continuing support of the Swedish Institute, Swedish Arts Council, the Embassy of Sweden in London and the Anglo-Swedish Literary Foundation. With the arrival of a new generation of translators, recent innovative chairpersons, more varied activities, and the active involvement of more members in the running of the association, SELTA is going from strength to strength.

Q: You were one of the original members of the Swedish Book Review editorial board when the journal began publication in 1983. This year, 2020, SBR embarks on a new phase as an online journal. To what do you attribute its survival in print for 36 years?

When, a couple of years after forming SELTA, we were offered a take-over of the journal Swedish Books, we as a committee would have turned it down had not one of our number, Laurie Thompson, expressed his individual willingness to be sole editor. His was a one-man labour of love alongside a full-time academic teaching post, but the journal would not have been possible without the contributions steadily forthcoming from the burgeoning community of translators of Swedish, primarily but not restricted to SELTA members. His and our slight scepticism about losing our identity by eventually merging with Norvik Press, then at the University of East Anglia and now at University College London, proved unfounded, and in fact this step provided the extra assistance and expertise which enabled our two subsequent editors to shoulder the task. The individual work and enthusiasm of the various guest editors and review editors over the years must also not be forgotten. And of course the journal would not have been viable at all without the financial and other practical support from the Swedish Arts Council and the three bodies mentioned earlier, as well as on occasion the Finnish Literature Information Centre in Helsinki and the Swedish Information Service in New York. Swedish Book Review faces a new digital future, and this we hope will be a turn in fortune, not a decline, and well in tune with the times.