‘The fluidity of a city can be very overpowering, both to write and to experience’

An interview with writer Tone Schunnesson

interviewed by Alex Fleming

For as long as they have existed, metropolises have inspired artists and writers around the globe. Over its storied history London has played host to many writers, poets and thinkers, fuelling encounters that have left their mark on literature as well as on the city itself. To explore this literary heritage, University College London (UCL) has created a multi-faceted initiative, Lost and Found: A European Literary Map of London. Through its digital map, cross-continental exhibitions and public events, the project reveals a London and a Europe of the imagination.

To mark this special issue on city writing – conceived as an homage to the European Literary Map of London – Swedish Book Review spoke to three contemporary writers from across Europe, Nisrine Mbarki Ben Ayad (the Netherlands), Tone Schunnesson (Sweden) and Iryna Shuvalova (Ukraine), for all of whom place plays an important part in their work. In this series of interviews, the writers discuss how they respond to the complex fabric of urban modernity, their relationships to London as a city, and the intersections of their various literary practices.

SBR: How important is place to you in your writing? What elements of cities do you personally respond to most?

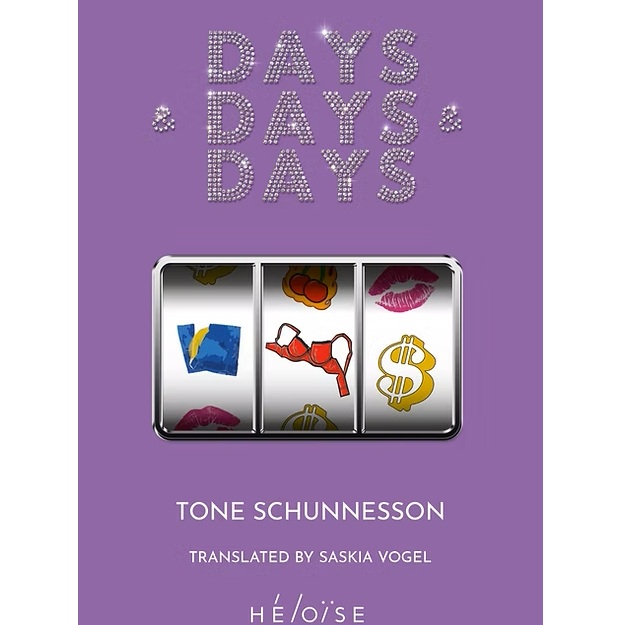

Tone Schunnesson: It all depends on what I’m writing. Place can be very specific or more allusive, depending on what the text needs. I’m working on a novel right now where the place where the story unfolds is more like a lost memory and not at all as clear as the city, Stockholm, in my last novel Dagarna, dagarna, dagarna (Days & Days & Days, published in Saskia Vogel's English translation by Héloïse Press).

For me personally, I love walking in cities and I love libraries. Places that are open to all. I also love parks and the people who hang around there during the day. The people who hang around in a park during a workday wouldn’t meet in any other setting.

How do you go about recreating the fluidity and texture of an urban landscape in your work?

I think it’s a combination of speed and detail. There’s some blurriness going on but also very clear pictures, like a rat crossing the street or a very ugly face or a very beautiful face or an accident. Sights that disturb the fluidity and erupt the impression of a city as a perfect, whole, ongoing thing. Because the fluidity of a city can be very overpowering, both to write and to experience. You have to look for eruptions and interruptions and try to insert yourself there.

In my last novel the character was born and raised in Stockholm, the city where the novel takes place, and she also sees the city through many different layers of memory and nostalgia. So that fluidity also has a familiarity and a longing for things that got lost or changed over time. For her the city is a constant reminder of failures and lost youth, and she feels the city turning away from her and towards younger generations. I have an impression that cities and youth have an ease towards each other.

In my last novel the character was born and raised in Stockholm, the city where the novel takes place, and she also sees the city through many different layers of memory and nostalgia.

The theme of this issue was inspired by the European Literary Map of London. What is your relationship to London as a city? Are there any particular works of literature or art that have shaped your vision of the city?

I love London and went there to visit my friends a lot in my early twenties. That experience was marked by transport. I couldn’t believe what a big role transport played in life, coming from a much smaller Swedish city where we rode bicycles everywhere. We were going out a lot in London and I was so fascinated and shocked that going home from the party was just as a big a part of the evening as going out. And it demanded just as much energy as getting ready! Coming to London the last couple of years, as a writer, I’ve felt a new kinship to the city. It really is a great city for walking, and I believe that walking and writing are intertwined.

Coming to London the last couple of years, as a writer, I’ve felt a new kinship to the city. It really is a great city for walking, and I believe that walking and writing are intertwined.

In addition to place, temporality is important in your work – Dagarna dagarna dagarna is very of our time in its discussion of influencers, capital and the attention economy. What about these systems and social structures appealed to you?

I’ve always been very fascinated with labour. I myself grew up in a bookstore, my dad was a small business owner and I always had this very practical way of thinking about books and literature. Books were just as much, if not more, for selling as they were for reading! And in a store at the time you handled a lot of cash, so every day I felt I could see how much that labour was valued. I always think this disenchantment was a part of me understanding Marxism almost at a cellular level.

When I myself became a writer I thought a lot about how you are a part of the gig economy when you are a writer, an artist, a freelance culture writer… jobs that in one way are very, very valued but at the same time very undervalued. The writer’s capital is hard to turn into actual capital; that doesn’t make the writer’s capital without worth, but what is its worth? Again, a disenchantment. And I think this led me to take an interest in people that are really suffering in the gig economy, like people delivering food etc., and reflect on how capital and tech and the new labour market have changed how we think about work forever. This experience, combined with my insane interest in fame culture and how you value fame, how you sustain that value etc. appealed to me in writing Dagarna, dagarna, dagarna. It allowed me to think about influencers, who are very overvalued but also very despised, as one part of the strange new labour market.

In addition to writing fiction and essays you also work across different media, in your work for the stage and as a cultural commentator. How do these inform your fiction (or not)?

My podcasting and writing as a cultural commentator are very different from my fiction! You have to be very aware of the world around you in being a commentator, be inviting to people and able and willing to explain yourself, whereas my fiction writing is more inward-looking and more opaque, especially to myself. And it’s much slower unfortunately hehe. But I also know I have something to learn from the slowness. I think my writing for the stage sits at a sweet spot in between the two, because it’s your work but you work with a group of people. And I love people!

Tone Schunnesson

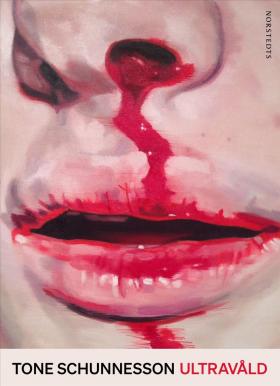

Tone Schunnesson is a Swedish writer. She studied Creative Writing and debuted in 2016 with Tripprapporter (Trip Reports, 2016), which received critical acclaim and was shortlisted for the Borås Tidning’s Debutant Prize. Her second novel, Dagarna dagarna dagarna (Days & Days & Days) was shortlisted for the EU Prize for Literature 2021 and for the Sveriges Radio Prize for Best Swedish Novel 2021. Her next novel, Ultravåld (Ultraviolence) will be published in Sweden in May 2026.