130 Years (and Counting) of Finland-Swedish Poetry

SBR interviews the editors of a new poetry anthology, Bländad av död och kärlek

by Darcy Hurford

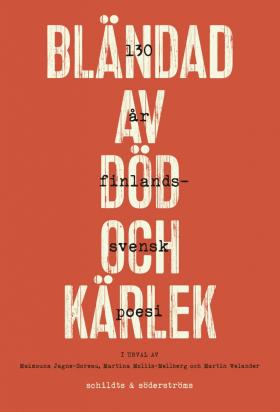

In 2021 an anthology of Finland-Swedish poetry appeared. This is noteworthy in itself, as anthologies of Finland-Swedish poetry don’t come around all that often. Its title, Bländad av död och kärlek (Blinded by Death and Love) is a line from a poem by Tua Forsström, one of the eighty poets included inside. What’s more, rather than follow a chronological or genre-based order, the 130 poems in Blinded… are organised into six chapters, each with a heading that suggests a mood or a feeling. It’s an approach that brings different poets together in surprising ways: Märta Tikkanen made her name as a feminist from the 1970s onwards, while Henry Parland was a prominent modernist half a century before, yet her 1978 poem about love ends up opposite his from 1929 in the section Om du kysser mig ikväll (‘If You Kiss Me This Evening’), casting a different light on both. Similar juxtapositions appear elsewhere with Mårten Westö (1990) followed by Gunnar Björling (1925) and Edith Södergran (1925) followed by Susanne Ringell (2012) – just to name some examples.

The anthology was compiled by three editors: Maïmouna Jagne-Soreau, post-doctoral researcher at the University of Helsinki who completed a PhD on postmigration literature in the Nordic countries in 2021, defending it both in Helsinki and at the Sorbonne; Martina Moliis-Mellberg, film critic, journalist and a poet who debuted with A in 2015 and has published four collections since; and Martin Welander, who completed a PhD at the University of Helsinki on the author R.R. Eklund’s aphorisms and is now publisher at Schildts & Söderströms. SBR interviewed Martin and Martina, and Maïmouna, who was unfortunately unable to be present, read and added comments to the text.

SBR: What made you decide to produce an anthology, and why did you choose to arrange poems by theme rather than, say, chronological order?

Martin: We took the initiative because Schildts & Söderströms was approaching its 130-year anniversary as a publisher. I suppose we could have held a banquet or published a commemorative volume or something, but that wouldn’t have been much fun, whereas an anthology of Finland-Swedish poetry was appealing because it’s been so long since anyone last took the risk of doing one. I don’t remember whose idea it was to arrange the poems by theme, but we did spend a lot of time discussing how to divide it up.

Martina: I don’t think anyone actually said ‘what if we did it this way?’ It was more a combination of talking a lot when we were getting started about what we did and didn’t want to do. Personally, when I agreed to be involved in this – which I was happy to do – my main concern was that I didn’t want to do a boring anthology, I didn’t want reading it to feel like work or a chore or schoolwork, I wanted us to maybe not bother about literary canons to some extent. Obviously, there are loads of poems in this book that you’d probably want to include anyway if you’re compiling an anthology of Finland-Swedish poetry, but I still think we’ve made a fairly unusual selection as well. I think that was something we talked about quite early on, we wanted to do it our own way, based on what we think is good, interesting and awakens a response in us, rather than ‘oh, but we must have that Södergran poem’, or whatever.

Martin: I think we also decided pretty early on what we didn’t want, and that was chronological order. Mostly because we all thought things get more exciting the closer you get to the present day, and we wanted to have scope to open with something striking. At some point we decided to follow a thematic structure so that each section, each chapter could have its own arc, its own rhythm, and we tried really hard to start off each chapter with a really great poem or one that speaks to us strongly. The book starts off with a poem by Emma Ahlgren from 2019, so it really feels new and recent. [Editor's note: a selection of poems by Emma Ahlgren is also included in this issue, in Nichola Smalley's translation.]

Swedish-speaking Finland [has] an incredibly strong poetry tradition, which might not always lead to people reading poetry but does mean there is this very strong desire to uphold it

SBR: Are there any poems you regret not including?

Martin: Yes, we all had our favourites, the question is: can we still remember them?

Martina: Well, I think I was extremely good at thumping the table until my favourites were included, but we all were really. Of course there are loads of poems we could have included, or would have liked to, but for me if there’s anything I regret in particular then it’s to do with poetry collections that came out right after we’d finished the anthology. There’ve been times when I’ve thought, ‘God, that poem would have been absolutely perfect if it had been published before we’d finished,’ and I guess that will keep happening to me for a few years.

Martin: It was brilliant to be working on this during the pandemic when people weren’t really meeting. We decided we would meet up here at the office, it was completely empty and we sat there in the big meeting room having very animated discussions. I remember they usually started with someone having planned a passionate plea in defence of some poem, and one of us would start and get fired up on behalf of a poem and sometimes it worked and sometimes it didn’t, which was still fine. Sometimes you could hold a fifteen-minute pitch about why a poem was brilliant and the other two would just say, well I hear you – but no. It still felt like you had been able to say your piece, and sometimes the others would say, well you’ve spoken so well about that poem, even if I don’t like it, I appreciate how strongly it resonates with you, so let’s include it, and then the next time you would get fired up about someone else’s favourite poem. So there was some give and take but I think it went quite well.

Martina: Also, I see it as a positive that we didn’t always agree, there were a lot of emotions involved but I don’t think we ever argued (unless I’ve forgotten), you could choose to agree or disagree. And once we’d come up with the different themes, you could think, well, that poem might not be a particular favourite of mine, but it would fit in really well in that theme. We could have wildly different ideas of what theme a poem belonged to because sometimes a poem would speak to us for very different reasons.

Martin: One thing we did argue about a bit, I seem to remember, was how many poems by a certain poet should be included. There’s an emphasis on certain poets who have several poems included whereas most poets only have one. Not that the number of poems necessarily matters, two really short poems might not be more than one that extends over two whole pages, but it was something we didn’t always see eye to eye on. It’s a pity Maïmouna isn’t here, because she often represented a different view. Martina and I, who both go back a long way with Finland-Swedish poetry, tended very much to agree on most things, which surprised us too. Maïmouna comes from France, where things like rhyming verse occupy a completely different position than in Finland-Swedish poetry and mean something else entirely, so she could place quite different emphasis on what was interesting. Otherwise Martina and I could have been completely blinded by our shared love of Tua Forsström – who has five poems in this anthology and has given it its name, but Maïmouna questioned whether Tua Forsström was really that good. And Elmer Diktonius, whose poetry neither of us really had much feeling for, we accepted its quality but it didn’t speak to us especially, whereas it did to Maïmouna. And it was good that happened sometimes.

Maïmouna: I reckon that Tua Forsström writes poems that evoke some kind of nostalgia for the Finnish-Swedish reader, but since I didn’t grow up in Finland I found it challenging, somehow defamiliarising, to emotionally connect to this nostalgia. Modernists like Diktonius, Södergran or Parland on the other hand, I experience their poetry as more timeless and universal, or at least in the European tradition of humanism. It was a real delight to weigh and consider all those aspects when debating what poems to include or not, from the point of view of content, of the meaning, but also the form of the poem, its musicality, its linguistic quality, its boldness etc.

A challenge for Finland-Swedish culture [is] how can we avoid being overly inward-looking without ceasing to exist or being absorbed into Finnish-speaking culture which is so strongly present around us.

SBR: Does poetry have a higher status in Swedish-speaking Finland than elsewhere?

Martin: I think it’s very strong here, I’ve become more and more convinced of that. Poetry still gets reviewed quite a lot here, which isn’t always the case in Finnish-speaking Finland or in Sweden. Obviously the print runs for poetry collections are small, but they aren’t all that much smaller than for Finnish-language poetry, so yes, we love our poets and we have so many that are absolutely outstanding.

SBR: If you consider the numbers of poets in relation to population size (Swedish-speaking Finns make up around 5.2% of Finland’s population) it’s pretty incredible…

Martina: Yes, Martin’s right that poetry is reviewed more here than in, say, Sweden, though when it comes to contemporary poetry I don’t know if it really has a stronger position. What Swedish-speaking Finland does have, though, is an incredibly strong poetry tradition, which might not always lead to people reading poetry but does mean there is this very strong desire to uphold it; Finland-Swedish poetry is considered as something fine we have, so that’s distinctive for Swedish-speaking Finland as a culture.

Martin: There are so few Swedish-speaking Finns that it’s not really possible for a really strong poetry subculture to exist, whereas in Finnish-speaking Finland and in Sweden it’s more that poetry has vanished from the culture section of the daily press but can be very prominent in the less mainstream media, in more peripheral publications. Finnish-language poetry can be reviewed in an incredibly knowledgeable way in specialised magazines like Nuori Voima or Tuli & savu and as a Finland-Swedish poet you might wish for that kind of highly knowledgeable reading, but on the other hand, you are still included as part of general culture.

SBR: The last time Swedish Book Review did a Finland-Swedish special issue was in 2013. How do you think Finland-Swedish literature has developed since then?

Martin: That’s a hard question.

Martina: That’s ten years!

In practical terms things have happened, I mean with publishing houses, and the book industry has changed an awful lot, not just in Swedish-speaking Finland but in general, the advance of audiobooks and all the worrying about how little people read, but that probably doesn’t affect what people write about; other things affect that. A lot has happened but it’s hard to have that kind of overview. Martin, do you see it differently, seeing as you work with it?

Martin: Yeah, thinking about ten years from the point of view of publishing, it’s about ten years since Schildts was merged with Söderströms, [the two publishing houses were formally merged in 2012] and now we’re back in a similar situation with two largish publishers [Förlaget M, the other major Swedish-language publisher in Finland, was founded in 2015] so we’re back in a similar situation to before the merger.

I think what’s significant is also what hasn’t happened. I think more has happened in Sweden, where audiobooks, for example, have really taken off in a major, rapid way. Finnish-language audiobooks have also gained ground rapidly lately, whereas in Swedish-speaking Finland the printed book has held its ground in the past ten years. Paper books are still doing well, we haven’t seen any dramatic changes in publishers’ publishing profiles or otherwise, so in comparison to what’s gone on elsewhere things are pretty stable really.

Martina: Yes, thinking about poetry, I think there has been pretty good growth: new poets have emerged, people make their debuts, people are still writing poetry, people want to publish poetry, and maybe that’s the case generally, but in a Finland-Swedish context, I think Finland-Swedish poetry is alive and well.

Almost every time I flick though this book I’m struck by how much incredibly good poetry there is. We’re immensely proud of this.

SBR: How do you feel about audiobooks? I see Schildts & Söderströms have just launched an audiobook writing competition.

Martin: That ties in with my earlier point that audiobooks haven’t taken off as massively here. We can see that audiobooks are massive at publishers in Sweden and at Finnish-language publishers here, and we see a risk that Finland-Swedish literature will get left behind or left outside, so, while we’re not planning to change our profile as paper books are doing well for us and we have a solid readership for them, we do want to see if there’s scope for a Finland-Swedish audiobook.

We’ve quite specifically stated that it needs to be Finland-Swedish so that we don’t end up publishing crime novels set in Skåne by authors from Sweden, ‘cos there’s no shortage of those. We want to keep promoting Finland-Swedish culture and specificities, that’s our unique selling point and raison d’être. But is there a chance of a Finland-Swedish audiobook appearing on Storytel’s top list that was written purely as an audiobook and could be part of Finland-Swedish culture? We do publish crime novels that work well as audiobooks, and we’ve been producing audiobooks for several years already. So this is a test to see if a Finland-Swedish audiobook bestseller is possible. You would think so.

SBR: How would you define Finland-Swedish literature? Edith Södergran, for example, who went to school in St Petersburg, could have written poetry in German?

Martin: We didn’t want to define it too strictly for Blinded by Death and Love...

Martina: But we did have that discussion: who should be included, who can be included. For example, we’ve included a poem by Cia Rinne that doesn’t actually contain a single word of Swedish, and we talked about it a lot. She’s a Swedish-speaking Finn, but doesn’t live in Finland and doesn’t primarily write in Swedish, so what should we do? We didn’t end up setting out definitive criteria, it was more about whether something felt Finland-Swedish or not, whether we wanted to include it.

Martin: We wanted to be inclusive, like with the audiobook competition, where we say we don’t have a definition of what a Finland-Swede is, you can decide that yourself, it’s not about what passport you hold or anything. And with Cia Rinne, we wondered whether the Swedish language was somehow a key criterion, but then again, she is a Swedish-speaking Finn, so we can be inclusive on that basis. It is a challenge for Finland-Swedish culture though: how can we avoid being overly inward-looking without ceasing to exist or being absorbed into Finnish-speaking culture which is so strongly present around us.

Martina: And it always revolves around two things: on the one hand, it’s essential to define things, but on the other hand it’s essential not to define things, you move between the two all the time, like a kind of pendulum.

Martin: And I’m glad it’s a movement, that it’s not stagnant or too clearly defined. That would be limiting.

Martina: Coming back to this book, there’s so much Finland-Swedish poetry out there that another book would be easy to do. Some of the feedback we’ve had has been that, oh, you didn’t include such and such a poem, but we just said no, this is 130 poems and there’s another 130 that could easily have been included, it’s not like there are only 130 good ones and then we ran out. There’s loads out there. This is a starting point.

Martin: And almost every time I flick though this book I’m struck by how much incredibly good poetry there is. We’re immensely proud of this. It’s a starting point and hopefully it’ll inspire someone else to come up with a response.

Bländad av död och kärlek

Schildts & Söderströms, 2021, 188 pages.

Maïmouna Jagne-Soreau is a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Helsinki. She completed a PhD on postmigration literature in the Nordic countries in 2021, defending it both in Helsinki and at the Sorbonne.

Martina Moliis-Mellberg is a poet and film critic. She debuted with A in 2015 and has published four poetry collections. Her first children's book was published in autumn 2023.

Martin Welander is a publisher at Schildts & Söderströms. He previously completed a PhD at the University of Helsinki on the author R.R. Eklund’s aphorisms.

D.E. Hurford is a translator from Estonian, Finnish and Swedish. She lives in Belgium.