from Best of Husbands

by Gun-Britt Sundström

introduced and translated by Kathy Saranpa

When Martina, a student at Stockholm University, finds a note on her desk that says ‘Gustav called’ and wonders who he is, she has no idea that she’s about to fall in love. The first-time reader of Maken (translator’s working title Best of Husbands) is equally unprepared for the turbulent relationship that they are about to have with Martina’s story.

Gun-Britt Sundström’s novel has engaged and provoked readers since it was published in 1976. It has appeared in several editions and continues to provide such contemporary authors as Sara Stridsberg with a source of inspiration. The concept of the Maken divorce became familiar in the 1970s, when wives realized they didn’t need to be married to be happy – and indeed might be happier alone.

The couple spend seven years of their lives, more or less, involved in a relationship that begins as a meeting of twin souls – Martina feels he’s not her other half, but rather her other whole – but quickly begins to show cracks. Gustav claims he’s found the love of his life and is eager to marry. Martina has come to the realisation that marriage is something that doesn’t suit her temperament, while new discoveries, conversations with strangers, and freedom do. In one scene, she pulls deep draughts on her pipe, blissful that she has no foetus to consider. Their negotiations, accusations and attempts to accommodate their needs for sexual intimacy, space and commitment form the core of the book; student life in Stockholm in the 1970s provides the backdrop.

Sundström is a stylistic wonder. Her words are carefully and precisely chosen. She gives the impression, however, of effortless and casual erudition. Her humour is impeccably timed and leavens what is often a narrative heavy on frustration and hopelessness. There is no happy ending here, but the journey is so compelling and rich in philosophical reflection that the reader doesn’t mind.

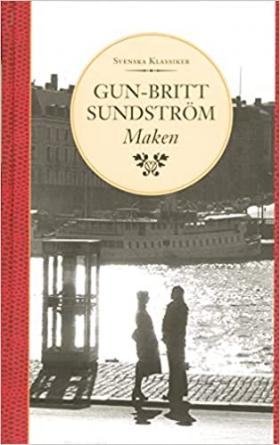

Page markings refer to the 2001 ‘Svenska klassiker’ edition, copyright Albert Bonniers förlag.

View a reading by Kathy Saranpa from Gun-Britt Sundström's Maken/Best of Husbands on Translators Aloud.

from Best of Husbands

pp. 25-30

On Saturday night, I had planned on inviting some old acquaintances to my new home, but Gustav is going out to the archipelago and wonders if I want to come along. And it occurs to me that I’m actually quite tired of my old acquaintances. It’s not appropriate for us to spend the night, of course, he says. I assume he’s joking and say that I don’t have to worry about anyone but myself. Since the connections this time of year are scheduled so far apart, we would simply be going out and turning around to come back. Taking the bus from Jarlaplan on Saturday morning, back with the boat from Hummelmora on Sunday evening – that sounds good, I think, after studying his schedules.

Gustav’s parents, however, don’t think it sounds good at all. They won’t let us go unless we have a chaperone along, he tells me on the phone on Friday, so now he’s talked to his brother, too, and by the way, they wondered if I had told my parents about our plans.

I’m so shocked that I start to hiccough. My parents? Chaperone? Gustav’s brother who doesn’t even live in Stockholm: does he have to make the whole trip just so … Am I the one who’s crazy, or is it someone else? Have I lived in freak circles, in which all the ideas about what’s appropriate in bourgeois society have been so thoroughly turned on their heads that I don’t know anymore? Or have I simply happened to fall into an enclave of residual 19th-century etiquette? What are they thinking? I’m an adult and single and independent (on government loans, of course), I have a flat where we’re free to wallow in lust and lechery for days on end if we wish – we don’t have to travel out to the archipelago for that.

‘Let’s just forget about it,’ I say. ‘I’d rather not go if there’s to be such a fuss about it.’

Gustav says, ‘That’s parents for you,’ as if there’s nothing to it, and he doesn’t understand how insulted I feel. It’s as if I’m 100 years old and have seen it all but have been posing as an innocent – I mean, this entire apparatus to protect the little family girl’s virginity and good reputation when, as it happens, there isn’t anything to protect. And if it’s Gustav we’re supposed to protect, it’s even worse – as if my intention were to ravish him as soon as we got the chance.

‘I feel like a bad girl. I am a bad girl if people think I am, because there’s no other meaning. A bad girl is something one is thought to be.’

‘In that case, I’m a bad boy,’ he says cheerfully.

‘You are most certainly not! You are such a horribly splendid boy that your parents are completely out of their minds and don’t believe two people can go out to the country for the weekend without raping each other, and, by the way, it’s completely different, because there are no boys who are so bad that they’re as bad as a bad girl. You know that as well as I do. And by all means, don’t let me drag you down in the mud.’

Gustav laughs; I emphasise that I see nothing amusing at all in the situation.

At the last moment his brother is unable to accompany us. However, his parents clearly feel it’s now too late to stop us. As far as I’m concerned, I’ve washed my hands of the whole affair and have explained that I’ll come along only if I’m left out of his family conflicts. He can manage those on his own.

Conflicts notwithstanding, I’m happy that we get to go. We leave behind us a city disfigured by election propaganda – idiotic posters on every single wall. So much the better that we can’t vote yet and can turn our backs on the city without feelings of guilt.

It takes over two hours to get to Gustav’s island, in total: we take the bus and the ferry and then another bus, and the last couple of kilometres we walk. There are few year-round residents left – only smallholders and retired people on government pensions. The rest of the farms have become vacation homes that are now closed up for the season. Clear, chilly air. Forest. Maples in their autumnal splendour and pines with lofty crowns. Trees. I become utterly awe-struck walking under these trees.

The road becomes increasingly narrow, and finally it’s simply a path. Then we’ve arrived. There are two buildings – one larger, insulated for winter, on the crest of the hill, and a smaller one below: a renovated fisherman’s hut. And then, the Sea. Gulls crying. (Terns, Gustav corrects, but I think ‘gulls’ sounds better.) We stand on the dock and witness the sun glittering on the water. We breathe.

But Gustav is hungry. He makes a fire in the stove up in the large house and goes out to chop more wood, leaving me to put on the potatoes and fry the sausage. I ask myself why I can’t be the one to chop the wood, but stand there with my question left unanswered and have to find pots in the cupboards and food in the sacks.

When we’ve cleaned up after our meal, we go out to inspect the property. Gustav’s ancestors were skerry farmers for generations, and he’s spent all of his childhood summers here. He shows me good climbing trees and boulders perfect for lookouts and the cove where he built cities in the sand, and I try to see it through his eyes although I know it’s impossible: it’s only by analogy that you can understand such things. It’s only by analogy to how you see the trees and the boulders from your own childhood.

At twilight, when it gets colder, we go inside and build up a fire, read for a while, drink tea and become so drowsy in the warm living room that we can no longer avoid the question that has now towered into a colossal problem: where are we going to sleep? I didn’t want to approach the subject first lest I stumble into new ridiculous difficulties, but now I’m so sleepy that I’ll do anything for a bed, anywhere, and when he asks my opinion, I say it’s probably most practical to sleep in this room, both of us, where it’s warm.

He raises no objections until we’re already in our beds, once we’ve distributed the blankets and extinguished the kerosene lamp on the tiny table between us and snuggled down and the rustling of bedding has ceased. Then he sighs in the darkness.

‘This night will change my life. I will never again be the same. I’ll be grey-haired tomorrow morning, or perhaps rather green-haired. Check my hair tomorrow and see if it isn’t green.”

‘What on earth. What do you mean?’ I sit up, uneasy, because the idea of changing someone’s life doesn’t appeal to me in the least. He doesn’t answer, and I tremble at the depths of my error – can he actually be as bound by convention as his parents?

‘Do you mean to say,’ I ask, incredulous, ‘that you’ve never slept in the same room as a girl before?’

He sighs.

‘Well then, maybe it’s time for you to have that experience as well.’

‘That’s true, but I didn’t expect there to be a flaming sword between us on that day.’

‘A flaming sword? How did that get here? I’m not the one who brought it in any case.’

‘Should I jump on top of you then?’

‘If you touch me, I’ll scream!’ I say and pull the blanket over my head.

He stretches his arm across the space between us and lays his hand next to my cheek. I pop my head out again:

‘As for me, I’ve slept in the same bed with men before, and nobody got green hair because of it.’ For clarification’s sake, I continue: ‘I don’t mean with my lovers. I mean I’ve slept in the same bed with men without lying with them and nobody got upset about it.’

‘Not even the man lying in it?’

‘Are you trying to be funny? In any event, we didn’t need any flaming sword to keep us from throwing ourselves at each other.’

‘You must have been keeping strange company.’

‘You’re the one who’s strange. Why wouldn’t you be able to sleep together in complete decency when you can do so many other things together in complete decency?’

He sighs again. I yawn irresistibly. ‘Can’t we table this discussion?’

‘Go ahead and sleep,’ he says, locking his hands behind his neck. ‘Sleep if you can.’

I puff up my pillow and assume my sleeping position, arms wrapped around it. ‘If you had something against this arrangement you could have said so from the beginning,’ I mumble into the pillow.

I ask myself if it’s possible that he expected me to seduce him, or if he thought that I thought he would, or if he’s hurt that I didn’t think anything at all, but I’m too ferociously sleepy to say anything more at all and fall brutally asleep, leaving him alone.

When I wake up, the room is empty. The sun is shining, and I dress and walk down to the sea to take in the morning and shake off the previous evening’s unpleasant mood. I’m as helpless as a child in these sexual dramatics. To discover that you’re wandering around causing fateful events without intending to or even noticing – it makes me feel like a monstrous combination of femme fatale and enfant terrible, and I want to go home. My instincts tell me to escape from this as quickly as possible, flee home where I can be the way I am and nobody has anything to say about it.

He’s bailing out a rowboat tied up at the end of the dock. There’s sun on the water, the September-blue water, and I sit on a rock on the shore. He’s moving around on the boat out there, coiling a line, tossing the oars and floorboards onto land – winter preparations. When he catches sight of me, he nods a good morning and gestures towards the house: ‘Coffee’s ready if you want some.’

Then he continues to work on the boat, turns his back on me and bails with the scoop. The water flies and glitters in the backlight.

I miss him. He turns his back on me and I miss him. I’ve hurt him, and I want to be comforted.

Later on, after lunch, I go for a walk in the light drizzle while Gustav takes a nap – he claims he didn’t get a wink last night. But he’s not getting any sleep now either: when I return and open the door carefully, he moves over so that I’ll come join him on the bed. So we simply lie there, not speaking, entangled in the warmth of each other’s bodies, and I would rather not waste one more word on the ridiculous situation of the previous night. But that’s not the way to solve misunderstandings. I hesitantly bring up the matter again and ask if he had a sex-negative upbringing given the family he grew up in.

‘On the contrary,’ he answers, ‘it’s a vulgar notion that Christians are sex-negative. Secularisation is what’s degraded the erotic.’

I have my doubts about this version of history, but he explains that it’s people who had a normal Swedish upbringing who consider sex to be a sort of dirty source of pleasure: ‘As for me, I was raised in the opposite spirit – that sexual intercourse is a way to praise the Creator.’

‘So you mean when we lie here holding each other it’s a kind of worship service?’

‘A little home devotional on a Sunday afternoon – do you have anything against that?’

‘I’m not really sure. You can’t really claim that it seems sex-negative, but it doesn’t exactly help to lessen the drama either. It doesn’t make our relationship any less complicated to have an unknown third party mixed up in it, does it?’

We lie quietly for a while, but someone has to keep feeding the fire in the stove. He gets up awkwardly and puts on several more pieces of wood.

‘Were you expecting me to seduce you yesterday?’ he asks.

‘No. Although it wouldn’t exactly have surprised me either.’

‘Would you have allowed yourself to be seduced?’

‘What kind of girl do you think I am?’

This seems to reassure him but also to raise some new questions, so I explain: ‘Not here and not now – we hardly know each other.’ (But someday, in a thousand years or so I mean, once we’ve known each other for a thousand years.)

‘Can’t we get to know each other?’

‘Isn’t that what we’re doing?’

He turns to me as he kneels before the fire and looks at me, doesn’t say anything, simply squints because of the smoke. Or maybe he’s laughing.

pp. 67-69

The morning paper says USA Ramps Up War: ‘Right Way to Bring Hanoi to the Table’. I read it with the usual combination of fear and a sort of horrible satisfaction: they’re making fools of themselves! They’re making bigger and bigger fools of themselves! Gustav comes up to return a book he borrowed from Harriet and we leave together – I’m going to the dry cleaners and he to the library. A completely normal day in our lives, a day when it’s good the way it is and can stay that way – the kind of day I love. There’s an autumnal chill in the air and he has a black rain cape that looks like it belongs to someone from an opera – Don Giovanni or Charles the XII, I can’t decide. It flaps in a fantastic way when he stops at the corner to wave.

I go on my errand and then I’m going to continue on to the English department, but I take the long way by Odenplan thinking that we may run into each other again, and we do, at the corner of Hagagatan.

‘Seldom meeting, swiftly leaving[1] he declaims.

‘Leaving swiftly,’ I correct. ‘It’s supposed to have internal rhyme.’

He has an exam in poetics in the afternoon. I think about it whilst I nod off through my grammar lecture (the fluorescent tube lighting in these airless caves they call lecture halls!). I think about how, if it had been ‘swiftly leaving,’ it wouldn’t have been that rhetorical figure, what’s it called? A chiasmus. I should have pointed that out to him in case he gets a question on it.

Cilla’s leafing through a bookstore catalogue – the sale’s just begun and I promised to go with her to the shop afterwards. When we come out, it’s begun to snow – small, sharp grains that sting our eyes. Even so, it’s a balm after the painful light and heat indoors. She comes home with me after our bookstore visit to have coffee. She’s realized that her ‘husband’ wasn’t worth having, anyway. Cilla says that you should do something with your life instead – join a study group for example. I tell her I started to attend one about developing countries, but I soon found it more efficient to read on my own.

We’re sitting in the fading afternoon light and talking about men and what we’re doing with our lives. It’s a completely normal day. Just as I’ve started to make dinner and put a pan of rice on the hob for myself (new eating habits), the phone rings. It’s Gustav, just returned from his exam.

‘Can you love a man who doesn’t know what a ballad strophe is?’

‘I love you just as you are. Do you have class tonight?’

‘Yes, but I’m skipping it. Besides, it’s cancelled because of snow.’

‘Harriet’s off to a concert. So if you want, you can stand under my window at eight. Don’t forget to pull your cape up over your face, though.’

It’s not that often that we have the opportunity to meet undisturbed, or without disturbing others. To be sure, Harriet and I have never forbidden each other men in our rooms, but our sense of delicacy prevents us from copulating right under each other’s noses: the walls are so thin you can hear the most delicate cough, and who feels entertained by listening to other people in the throes of passion? Neither of us, in any event. So Harriet has season concert tickets and I have a Film Club subscription.

When she comes home around 11, Gustav and I are once again engaged in virtuous conversation about freedom of will and the substantial self. About equality and performance prejudices and believing that you’re someone. I’ve realized that no person is anything. Gustav has realized that all persons are something. The question is whether we actually believe the same thing.

‘I don’t think I’m anything,’ I say, ‘but since nobody else is anything then I have just as much value as everyone else.’

‘I don’t know if I am anything, but maybe I could become something. If we put together the two of us who aren’t anything, maybe we can be something together.’

‘What, for example?’

‘Hmm, a happy marriage for example.’

‘That would at least be original,’ I admit. ‘It would satisfy my search for originality. You so seldom see a happy marriage.’

‘Erik’s been married for five years now,’ he says, to justify. It’s uncertain what this has to do with the subject we’re discussing, but I don’t ask about whether Erik is happy or not. Instead I ask, ‘In five years – do you think we’ll be around then? Do you think the world will still exist?’ (USA Ramps Up War: ‘Right Way to Bring Hanoi to the Table’.)

‘I suppose so.’

‘In ten years, then?’

‘Maybe the world, maybe not humans.’

‘I mean humans. This world.’

‘No, I don’t think this world will exist in ten years.’

Then he laughs – as if he knows something about it – and throws on his cloak to wade through the slush.

‘Seldom meeting, leaving swiftly,’ I say, ‘is a chiasmus.’

‘No it’s not. It’s a living hell,’ Gustav says, and wraps me in his arms once again in a fantastic flapping of his rain cloak.

- [1] A line from a poem by Erik Axel Karlfeldt, ‘Intet är som väntanstider’.

Maken

Albert Bonniers förlag, 1976, 379 pages

Foreign rights: the author.

We are grateful to the author for permission to publish this translated extract.

Gun-Britt Sundström is a writer, critic and translator. She made her debut in 1966 with Student -64 and has since published sixteen books, of which six for children. Her 1976 novel Maken is considered a modern classic. In 2019 she was awarded the Helgapriset literary prize.

Kathy Saranpa was born in the US and now works as a literary translator in Germany. A teacher and freelance translator of commercial texts, she caught the literary translating bug when she worked on rendering Ingrid and Joachim Wall’s A Silenced Voice into English (Amazon Crossing, 2020).