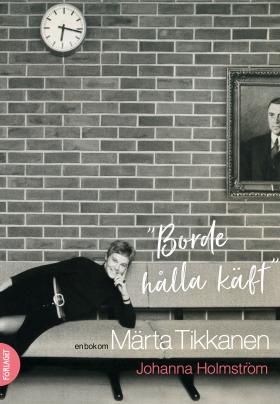

Borde hålla käft – en bok om Märta Tikkanen

(Ought to shut up – a book about Märta Tikkanen)

by Johanna Holmström

reviewed by Kate Lambert

'What was the most important thing about your writing?’ Johanna Holmström asks in their last interview. ‘I hope I have given others comfort and support,’ Märta Tikkanen replies. ‘I will always remember that grey little lady after the performance of Århundradets kärlekssaga [The Love Story of the Century] at the Burgtheater in Vienna who said she knew exactly what I was talking about because I was talking about her life. Except she hadn’t ever been able to say it out loud. Most people don’t have the opportunity to put their experience into words or have their observations printed. Those who do therefore have a responsibility. There is a female experience and it must be shared and made public.'

As one would expect, Holmström’s biography takes us through Märta Tikkanen’s life from her childhood in repressive Swedish-speaking Helsinki in the 1930s, evacuation to Sweden in the Second World War and her first marriage, to her affair with and marriage to writer and artist Henrik Tikkanen, her writing career, and her life in the decades after Henrik’s death, taking lovers and railing at critics. In Finland, controversy arose over Holmström having uncovered the identity of one such lover. The published book no longer names him.

In their first meeting, Holmström promises Tikkanen that this book will focus solely on her and her books. It won’t be about Henrik. Märta is delighted but the promise proves impossible to keep. Both Märta and Henrik described their turbulent marriage and his alcoholism in semi-autobiographical fiction. ‘Life is material,’ says Märta in a discussion of Karl Ove Knausgård and today’s autofiction. In this, as in her feminist writing, she was ahead of her time.

Johanna Holmström details her interviews with Märta and with three of her children. The domestic conflict and its impact on the children is an uncomfortable read. ‘Why didn’t she leave?’ is the question perplexing the author as she embarks on the biography project. We gain an understanding of the personalities, family history and social climate that influenced the choices made and their knock-on effects.

The biography is not only about the Tikkanens’ marriage, inescapable though it may be. Johanna Holmström had access to Märta’s correspondence with Åsa Moberg and Birgitta Stenberg and their letters demonstrate a warm and supportive friendship lasting decades. She also studies reviews of the books in the Swedish-language and Finnish-language press in Finland, and in the Swedish market, shedding light on their differing reception, the literary climate and the acceptability of feminist voices in the different countries over Märta Tikkanen’s long career.

Of course there are also detailed descriptions of each of Märta Tikkanen’s books; here set in their domestic and societal context. Familiar with several but not all, I am now keen to read more, including Män kan inte våldtas (Manrape) in which a woman attempts to exact revenge on her rapist. It was published in 1975, more than forty years before #metoo or I may destroy you. Jörn Donner directed a film version in 1978 but the biography ends with it about to be performed on stage in Finland for the very first time. In 2020.

In the world outside Scandinavia, Märta Tikkanen’s work has now become better-known than Henrik’s but neither are household names as they once were in Finland. To a foreign audience, the biography therefore provides the perhaps unknown background to her most popular work internationally, Århundradets kärlekssaga, detailing the lived experience that inspired it.

The biographical approach is personal. Holmström describes her visits to interview Tikkanen in the first person and in the present tense, initially sharing her trepidation at the first meeting and seeing her subject coming down the street with her shopping. The book ends with a description of a recent night out, a #metoo incident for the author herself. I was expecting objectivity but the first-person narrative of the biographer herself makes this an accessible and engaging read. Since a biographer will always filter the subject through the lens of their own experience, perhaps it is an advantage to have that personal angle stated upfront. We are clear that this is a twenty-first century feminist, who has divorced an abusive husband, examining the life of a 1970s feminist born in the 1930s who did not divorce her abusive husband. On balance, this extra dimension – the dialogue between a ground-breaking second wave feminist and a feminist of the #metoo era as the latter attempts to understand the former and the context in which she made the decisions she did – can be seen as one of the book’s strengths.

Borde hålla käft

Förlaget (Finland), Norstedts (Sweden), 2020

432 pages

Foreign rights: Federico Ambrosini, Salomonsson Agency

Swedish Book Review has previously reviewed and published extracts from Johanna Holmström’s novels Själarnas ö (Island of Souls), translated by Fiona Graham, and Asfaltänglar (Asphalt Angels), translated by Nichola Smalley.