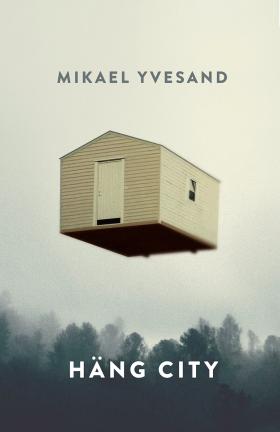

from Hang City

by Mikael Yvesand

introduced and translated by Sophie Ruthven

There was a time, to some not that long ago, though to many already in the distant past, where it was actually possible to get really, really bored. So bored that everything started to be an adventure.

In 1999, an unnamed, thirteen-year-old narrator and his two friends find themselves on the cusp between childhood and teenagerdom, dial-up and broadband, under the near-nightless summer sky of northern Sweden. The parents seem to have all but disappeared. Time extends to fill the space left vacant by the end of the school year, and all that is left to do is hang out with each other in an endless swirl of not-quite happenings. Imagination rules with its own logic of play, and leads the friends to focus their whole attention on the construction of a shack for themselves in the urban copse between a daycare and a health centre: Hang City.

I typically fail to understand why old people think it’s relaxing to be ‘at the summer cottage’. The older I get, the more stressed out I get by the thought of all the action I’m missing in town.

In his debut novel, which won the 2023 Borås Tidning’s Debutant Prize, Yvesand has perfectly captured the dreaminess not only of bright, long summers but also the voice and energy of a thirteen-year-old. The narrative voice blends the consideration and conviction of an adult with a child’s viewpoint, and while this may seem amusing to the older reader, I remember these thoughts well, or at least I think I do. I certainly remember having knowledgeable opinions about enigmatic adults, based on concrete, intellectual observation, though I may have drawn false conclusions, something mirrored in the fact that adults also have the occasional tendency to view children as somewhat hard-to-decipher entities. Despite inhabiting such separate spheres of experience, the age groups nevertheless frequently brush against each other’s worlds without truly being able to process them. Then there is the timeline we begin to ascribe to our experiences as we get older, something totally absent in the days of youngest youth. Yvesand himself has expressed mixed feelings towards plot (link in Swedish). From the Hang City narrator’s perspective, things happen, then more things happen. That seems like childhood. Sometimes you remember an event from the distant past in technicolour. Then your friend says something, and there it is: another event. Somehow, the novel ostensibly without a plot doesn’t need one at all.

Millennial nostalgia may play a part in readers’ interest here, but it’s just one flavour of the world. Hang City happens to be set at the end of the nineties, and whilst the backdrop is certainly of a specific vintage, any joyous escapism that the book provides comes from reliving that specific kind of transnational, transtemporal flight particular to the tail-end of childhood.

The translation below takes three extracts from the first half of the novel, as the friends begin the Hang City project, blissfully unaware of how strongly the imagination of their hometown, Luleå, has been gripped by something altogether more serious. A horrific murder has taken place, and the friends’ escapades seem to grow ever more innocent as they are interspersed with a series of letters, police memos and reportage relating to the investigation taking place above their heads.

from Hang City

The woods behind the health centre are actually minimal, by definition it’s probably a copse, but you only need to get a few metres in to be invisible to the adults on their verandas. It’s a place that only exists in the summer, when the trees are leafy enough to surround you ten steps away from the path. We’ve tried being there in the winter, but then you’re just a sad child in the tundra. Certain things in the woods endure. The beaten footpath to the fireplace, a yellow-painted park bench we swiped from the nearby cycle path, and a buried safe where we store stolen goods like snus and drinks cans, but most of it has to be redone each summer.

It’s started getting late by the time we arrive. We sword-fence our way through the bushes to the footpath. Jocke and Davve have already made certain preparations. Near the fireplace is a pile of boards and logs, two pallets that we nicked from the ICA supermarket at Björks and balanced on the bike saddle the whole eternally long walk back to Hertsön, and a heavy, black rubber mat that the children in the nearby daycare had used to stamp their boots clean until we stole it and hauled it off to the woods. Ultimately this will all become a shack, in some way. Davve is the brains. By the pile of junk in Hang City central there’s a single birch tree left standing. The bark is charred from all the times we’ve burnt litter. Davve has hammered a wedge of metal into the tree trunk, which can be used as a bottle opener.

‘Man, we’ve gotta get a tarp or something for if it rains, and like, have firewood somewhere.’

From above it’s an island in the forest. A kidney-shaped steppe of pines and beaten dirt. If it rains you can’t start a fire for several days. It’s untenable. We need a roof. Resources. I remember there’s a load of building material at our summer cottage in Lövskär.

‘There’s a load of shit left over from when we remodelled the cottage, and the storeroom’s full of firewood. Sure as hell there’s a load of old sheet metal by the harbour we can grab too.’ I think it was Jocke who got obsessed with the idea of having a metal roof, so that it patters the right way when it rains.

‘But how the hell are we gonna get all that shit from your cottage to here?’ Davve asks.

I haven’t thought that far. Of course, neither has Jocke, but he still comes out with some vague assurance that it’s ‘no biggie’.

‘Man, it’s gonna take fourteen months to walk, one way.’ Davve is a realist, perhaps a pessimist, but his scepticism often proves well-founded. He’s a little precocious, often wonders what ‘the point’ of various things is. Jocke is the total opposite. You could wake him up in the middle of the night and say: ‘come on, we’re off to Kalix, it’ll be fun,’ and he’d follow along without question.

‘You just want to keep partying all the time, right,’ Jocke says at least once a week. Though his definition of party is unclear. We’re too young to drink alcohol in the same way as many people I know. I generally associate that with endless darkness anyway. Malin Jakobsson, who’ll turn up to a disco on unsteady legs, only to be bawling her mascara out in the front seat of her mum’s car two hours later. Erika Andersson, who sleeps in the snow in the centre of Porsön. All the stories of people who’ve been stomach-pumped, whatever that means, and then the social services. Jocke strives for a reasonable amount of action in his surroundings. Climbing onto a roof, swimming in the rain, or scratching all the cars on Körsbärsstigen. Taking a walk to Lövskär to collect metal is definitely a party.

[…] both Thomas and Åsa have noted several unexplained occurrences at their home this spring and summer. Doors locked in the evening have, in the morning, been found unlocked and the mosquito nets removed from the windows. A window looking out onto the veranda has been replaced by Thomas after his having found a small, circular hole at the height of the locking device. Thomas no longer has the old windowpane but has stated that the hole was about 4–5 millimetres in diameter. During the Easter holiday week of 1999 the phone rang multiple times. Thomas himself answered about 5 times, but the person at the other end always hung up. The telephone also rang during the daytime when Thomas and Åsa’s daughter, Hanna, was alone at home. Only after the fact has Thomas realised that the calls could have been made by the same person. Neither Thomas nor Åsa connected the events or saw any cause for concern at the time. Thomas also wants to provide information about an event at the beginning of June, when Hanna came into her parents’ bedroom and asked whether Thomas had just been outside. Thomas, who had been sleeping for several hours, answered no and asked why she had thought this. Hanna answered that she had seen a silhouette outside her window. Thomas thought that Hanna had mistakenly assumed some swaying branches or similar to be a person, and didn’t think any more of the matter but instead went back to sleep. Shortly afterwards, Thomas was woken again, this time by his five-year-old son, Jonathan, who said that there was a guy with dirt on his face upside down outside his window. Thomas checked Jonathan’s room and then did a round of the whole house with a torch but saw nothing. Now that Thomas has read about the incident with the family in Hertsön, he wonders if these observations might be of relevance to the police’s murder investigation.

Servus is civilisation’s last outpost before the woods completely take over. If we don’t buy what we need for the journey here, we’ll die lying flat on our backs on Lövvskär Road, whilst vultures tear our eyes out of their holes. The air flutters. Jocke has his T-shirt twisted like a turban round his head. I’m blinded by his concave torso in the sun. We pass through Servus’s automatic doors. Inside the air is cool. The fizzy drinks fridge hums. Some old dude with a single can of Falcon beer and a bright white processed loaf of bread in his shopping basket is shuffling about, his mouth drooping. A red-haired checkout lady is sitting with her elbows on the stationary belt. A life-weary mum’s flip flops slap against the cold stone floor. She pulls a pack of cigarettes from the shelf and waits with her hand on her hip for her son to choose an ice cream, completely oblivious as to how important this decision is for a five-year-old. We continue further in. Just getting here, like, a tenth of the way, has been draining.

The selection at Servus is strange. Its location between the Hertsön Metropolis and Lövskär’s blokeish low-lifes means they have to sell both snacks and fishing wobblers. The crisp shelf is weak. We stock a basket with two bags of sour cream and onion and some sort of shitcrisps without crinkles that Jocke chooses. I hate flavoured crisps without crinkles. It reminds me of being unhappy in a caravan. Of sitting and eating crisp crumbs out of a Tupperware whilst the adults celebrate Midsummer on the other side of the tinted plastic window. I have, in general, always been more of a sweets person. Raspberry and cola laces with chocolate elephants and salted liquorice Lakrisal as a contrast. If you want to be able to eat a lot of sweets, which you do, you’ve got to cover the whole spectrum. You can eat a lot more sweets than you think, if only you have balance and believe in yourself.

Davve chooses a bag of sugary Haribo Peaches, which in principle is fine but somehow too decadent. They’d have been good in a mix with something more demanding, perhaps one salted liquorice monkey per ten peaches. My sister once ate herself sick on peaches. A whole bag eaten on the warm backseat of our car whilst we waited outside the petrol station on the corner of Bodenvägen and Gammelstadsvägen. I could understand her disgust so well that it later came to afflict even me. Chocolate I view as food. To sweets what bananas are to fruit. An uninspiring wrapped potato, but it feels irresponsible not to knock a few bars of Marabou Schweizer Nut chocolate into the basket. If I don’t punish myself, someone else will. Somewhere we realise that we are going to need real food too, and grab two packets of Dennis hotdogs, bread, ketchup and mustard.

Häng city

Bokförlaget Polaris, 2022, 272 pages

Rights: Gustaf Bonde, Bokförlaget Polaris

We are grateful to Bokförlaget Polaris and to Mikael Yvesand for granting permission to publish this translated extract.

Winner of Borås Tidning’s Debutant Prize and the Norrland Literature Prize.

Mikael Yvesand was born in 1986 and grew up in Luleå. Häng City is his literary debut.

Sophie Ruthven is a translator from Swedish, Norwegian and German, as well as general language lover. Also a ski instructor and artist, she lives in Innsbruck.