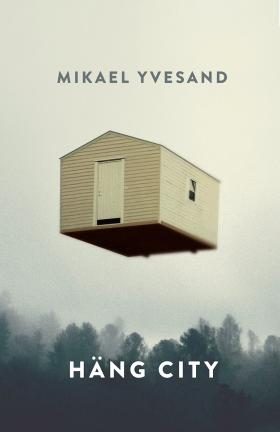

Häng City

(Hang City)

by Mikael Yvesand

reviewed by Sophie Ruthven

The year before the millennium marks a peculiar threshold in history, due perhaps a review by the writers who were children and young adults at the time. Obviously a world without smartphones, it pays to remember that this was also the moment just before the wide adoption of the internet brought about by broadband. Readers of Häng City born any time before the mid-1990s will feel wrapped in a warm blanket of nostalgia, especially those who were young at the time. Nostalgia with a sense of wistfulness for the time when you only had contact with people when you actually saw them, replayed the same video countless times and actually, well, got really bored.

The unnamed narrator and his two friends Davve and Jocke are about to enter the next phase of school, and the next phase of life. It’s a time when building a den might give you the same thrill as a crush, although you see the irony in children’s games and don’t actually know what you want from the girl you like. The logic and boundless energy of childhood reigns, and we are quick to no longer question them spending the long summer holiday without adults, caught up in their own world of urban Luleå and the surrounding nature. They industriously focus on building a hut for themselves in the sheltering copse between a kindergarten and a health centre, a space which, much like this moment in time, only exists briefly. This is Häng City. Events seem to occur one after the other without obvious connection, though every feeling and experience important to them is rendered crystal clear, and there are facts about the world that cannot be doubted. The narrator’s convictions often sound adult in formulation yet childlike in their viewpoint, such as his explanation of how to successfully eat a lot of pick ‘n’ mix:

If you want to be able to eat a lot of sweets, which you do, you’ve got to cover the whole spectrum. You can eat a lot more sweets than you think, if only you have balance and believe in yourself. Davve chooses a bag of sugary Haribo Peaches, which in principle is fine but somehow too decadent. They’d have been good in a mix with something more demanding, perhaps one salted liquorice Djungelvrål per ten peaches. My sister once ate herself sick on peaches.

Particularly impressive is Yvesand’s rendition of how children and teenagers play with language to make it their own. Even if they never name their friends – what is the narrator called? – they create that group-denoting slang we hopefully all remember. This includes the origins of some of the groups’ most favoured words and phrases, such as the titular Häng City:

A few years ago, a fast-food restaurant opened near the Systembolaget in Örnäset. They chose the unambitious name ‘Food City’, which consequently led to us to start naming things after their distinctive characteristic followed by ‘city’. One time, for example, Davve said that we should go to the disco in Örnäset because it would be Ass City. Still evenings without wind are, as a rule, Midge City. Next to the health centre by Jocke’s and Davve’s is Hang City.

An initially surprising element of Häng City is the addition of a crime, which appears via an irregular series of police reports. While it might be natural to expect a dovetailing of events, eventually you realise that this is, in fact, unlikely to ever happen. The three friends, whilst placing huge significance on some things (like how to lay out your clothes at night so they don’t get envious of each other) seem to see the horrific crime which happened to a neighbour they know as scary, yet ultimately impossible to understand and not immediately pressing. Existential thoughts of death do crop up, but at this age, they are not lasting. The friends are right on the edge of realising the gravity of life, and yet still not quite there. In fact, it is almost comic how, as the reader learns increasingly more about the crime, the friends remain only anxious, not directly curious. While it’s almost tragic as they ignore the visceral grief of the dead woman’s mother, such are the emotional limits of being eleven to thirteen.

Yvesand’s language is pitch-perfect, the humour is dry and will cause some out-loud chuckles on quiet summer trains, and the rich detail of everyday places and items will give readers the feeling of knowing Luleå inside-out by the last page: even if that knowledge is from the perspective of young people who use a town and its surrounding nature in quite a different way to adults. It’s hard to say whether anything really happens, but that only serves to underline the realism of summer in a small city – and who honestly experiences childhood as a consequential series of events that make a plot? Perhaps it’s not always the language of youth we’re reading, but Yvesand’s own delightful way of seeing things.

Häng City

Bokförlaget Polaris, 2022.

310 pages.

Foreign rights: Gustaf Bonde, Bokförlaget Polaris.

Winner of Borås Tidningen’s Debutant Prize and nominated for the 2023 Katapult Prize.

Mikael Yvesand was born in 1986 and grew up in Luleå. Many of the experiences in Häng City come from his own memories.