from The Purpose of Bees

by Göran Bergengren

translated by Fiona Graham

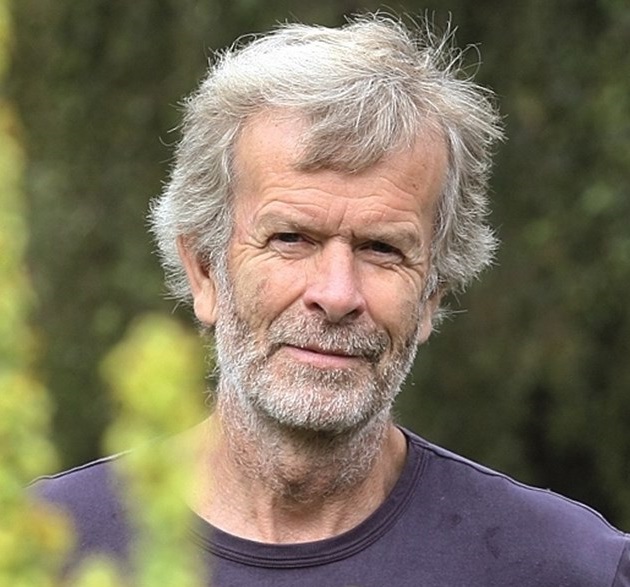

Göran Bergengren, one of Sweden’s foremost nature writers, is celebrated for combining the expertise of a naturalist with the sensibility of a poet. In a career spanning more than fifty years he has published over thirty nature books for both adults and children, for which he has received a number of awards – most recently Samfundet De Nio’s special prize in 2019.

In his recent work, Meningen med bin (The Purpose of Bees), he commits to paper some of the expertise gained in over forty years of beekeeping. In short, captivating essays that blend personal experience with extraordinary facts, Bergengren celebrates the often unseen lives of these remarkable insects and the role that they play in our world.

from The Purpose of Bees

Peach Blossoms

We have a spacious glasshouse some forty square metres in size. Though vacant in spring, by late August it’s a jungle of tomatoes, peppers, vines and cucumbers. One spring many years ago, in that disconcerting, warm emptiness, I planted a peach tree by the west-facing windows. I thought there’d be ample room there. Young saplings fresh from the plant nursery are puny little things.

Some years later – maybe seven or eight – the tree was gradually poking its way out through the pitched roof. I’d pruned it several times, but soon realised that a great many buds were going to waste, leaving gaps between the fruits. And the energy reserved for growth was manifesting itself in other ways: in roots that extended like an expanding hydra into the tomato beds, and, not least, in a growing patch of shade. Moreover, scale insects thrive on the Prunus family when conditions are dry and warm. These tiny, flat, slightly sticky creatures returned time and again. Clearly, a peach tree needs a greenhouse to itself, with ample room to expand into.

But some springs, before I was forced to banish the tree, were heady with pink peach blossom. And with its scent! You’d step into an enchanted fragrance whose impact was all the stronger because nothing else was yet making its presence felt. Tomato plants don’t usually make their appearance until the end of April, and often the peach blossom would already be in full bloom by late March. In the first few years I used an artist’s brush to pollinate the flowers, with unremarkable results.

Mimicking an insect is no simple matter.

But one warm March day – both spring and Easter were early that year, it might even have been on Good Friday – I let the bees in. They were very active in the spring warmth and were buzzing busily around the sallow trees. Quantities of them flew across the hedged-in fields in their heavy, yellow, pollen-laden breeches.

Usually, bees flying into a greenhouse are at quite the wrong address; it’s not easy for a bee to find its way out through a doorway with its sun compass, and with glass panes to confuse it. But as luck would have it, the greenhouse had been made to measure using large panes from forcing beds. They came from my grandfather’s market garden, which once had extensive raised beds with early vegetables and seedlings ready to be planted out. In our glasshouse, the panes were placed at a slight angle, with nails to hold them in place. It was easy to open them.

I removed a couple of them from beside the peach tree and stood for a moment breathing in the blossom-scented air that swept out with the warmth from the glasshouse. I sat for a while on the bench beside the door, watching the clock. It took precisely five minutes until the first scout flew in. After all, the tree might just as well have been outside the glasshouse. Moreover, the extra warmth around it was a godsend for bees. It was at least twenty-five degrees for some time after I’d removed the panes. That warmth gives bees a little extra boost, especially on a day in March.

And whilst I busied myself with a more down-to-earth task – carrying in manure and digging it into the seedbeds – the peach spring acquired a musical instrument. Soon it was humming like a moment in May, the time when fruit trees are in full bloom. Within the hour, you could be sure that each and every flower had had a visitor and been pollinated.

For the bees, this interchange, this traffic in and out of the tree, must have been the day’s scoop.

As expected, this resulted in a bountiful crop of peaches, although the fruits were small and had to be thinned out. But they all tasted delicious. The tree has been gone for several years now: as I said, it sabotaged itself. But there are times when I think about arranging some more peach years, partly for the harmony, the music of the bees, the exchange.

There are a thousand ways to gain an impression of bees’ sense of smell. The peach blossoms revealed how keen that sense is: a biological tool of unfathomable sophistication.

In a word, bees’ sense of smell is magical.

A bee’s ‘nose’ resides in its antennae, where the sensory nerves end in tiny odour receptors, minute discs that look like a mass of light dots under the microscope. Those who have done the sums know that the worker bee has six thousand such receptors, while the drone, with his vastly superior olfactory organ, has no fewer than sixty thousand – enabling him to locate, in a twinkling of an eye, a nubile queen bee on her way out.

The queen, who rarely leaves the hive, makes do with a mere two thousand. The opening of each receptor is covered by a delicate membrane that allows air to pass through, but excludes moisture, all of this in a forest of fine sensory hairs.

Thanks to its sense of smell, a bee can recognise a fellow member of its own bee colony from among thousands of others. Its own odour is the silent password it uses to gain admission to its home hive. This scent – its ‘ID’ – emanates from a gland common to all bees, located beside the rings that encircle their abdomen.

As we would expect, the bee’s sense of smell also plays a vital role in enabling the insect to distinguish between different sources of nectar. The first scout bee that flew in around the peach tree and then home to pass the message on to others also bore the scent and samples of the taste of the pink blossoms, in the form of pollen or nectar. Every worker bee who finds a good spot to gather sustenance acts likewise. All of them, moreover, have altruism as their hallmark.

And so the bee who has discovered the peach tree darts into the darkness of the hive and begins what’s known as the ‘nectar dance.’ This is a complex communication taking the form of movements performed on the honeycomb. If the distance is short – under eighty metres – the dance is rapid and circular, first to the right, then to the left, conveying information about the degree of proximity: the bees’ hive-mates fly out with the scent of peach blossom as their lodestar. Thanks to the dance and the right scent, the swarm that heads out towards the glasshouse swiftly finds its way. In this particular case it was unusually easy, being so close by. So it was hardly surprising that so many arrived in no time at all.

If the source of nectar is a long way off, the dance will be different (figures of eight, double circles), a movement whose pattern depends on the nature of the discovery. The rhythm of the dance and the number of oscillations of the bee’s abdomen per unit of time indicate the distance. To convey information about the direction, the axis of the insect’s movements is correlated with the position of the sun. And so is the angle at which the waggling dance is performed, which concludes the message.

Where necessary, bees can follow this guidance for up to three kilometres in open terrain. A colony of bees generally has a flight radius of just over a kilometre. At that distance, bees’ orientation is so accurate that if they do miss a source of nectar, it is often by no more than a few metres.

To tempt them further afield, there needs to be an abundance of food worth the effort.

Peach blossoms should do the trick.

Meningen med bin

Carlsson Bokförlag, 2018, 160 pages

Foreign rights: the author; contact the publisher.

We are grateful to Carlsson Bokförlag and Göran Bergengren for permission to publish this translated extract.

Göran Bergengren is a writer and biologist who has published many books on the natural world. Over his career he has been recipient of numerous awards, including Samfundet De Nio’s special prize in 2019.

Fiona Graham is a translator and editor working from Swedish, Dutch, German and other languages.