from Giraffe Island

by Sofia Chanfreau and Amanda Chanfreau

translated by Julia Marshall

Vega is ten years old and lives with her father on Giraffe Island. Life ambles along as usual, which for Vega is anything but: seen through her imaginative eyes the world around her is brimming with adventure, with fantastical creatures and morphing objects to be found at every turn.

Though Vega has a close relationship with her loving – if distracted – father and vivacious grandfather Hector, they struggle to answer the questions Vega has about her mother. And so, when the foundations of her stable life start to shift, Vega decides to set out on an adventure to find out more about her mother – and about herself.

With its magical-realist tint, gentle humour and captivating illustrations, Giraffe Island has won over critics, readers and prize juries alike. This excerpt is taken from chapter two of the book, when Vega pays a visit to her grandfather, Hector, whose exuberant nature, tall tales and lush garden full of treasures offer a retreat for Vega in times good and bad.

Giraffe Island, translated by Julia Marshall, will be published by Gecko Press in 2024.

from Giraffe Island

Chapter 2

An octopus has three hearts

If you take the path past Reningsverket and up to Lotsberget, past Lotsstugan where the famous banjo player Ylva String grew up, and then go along the cliff edge with forest on one side and a gaping drop to the water on the other, you’ll come eventually to a yellow fence. You can also take the gravel road on the other side of the mountain to get here, which is quicker and easier. But Vega preferred to take the path past Lotsstugan when she went to see Hector. The animals she met up on the mountain were exciting and different, often camouflaged as rocks or trees. A rocky outcrop would suddenly quiver and give rise to a herd of mossy stone lions, or green hedgehogs as big as Saint Bernards would be scuttling about under the spruce trees.

Hector was Vega’s grandfather. Fantastic things always happened in his company. Vega went to his house after school when she felt extra happy or extra sad or extra angry. It didn’t matter how she felt because with Hector she could be exactly as she wanted. She didn’t need to pretend or make things up, Hector always believed everything she said. He laughed so hard the gold teeth gleamed at the back of his mouth, and he fished his big ears out from under his hair to listen what she had to say.

He asked about the animals she’d met that day, how they were doing, and suggested she invite them for coffee next time they turned up.

Hector was never worried about Vega. He had no clouds over his head and his eyebrows were definitely never steep like rooftops. His nose was as big as an eagle’s beak, with a little swing-up at the bottom, like a ski jump. Hector was old, but he had almost no wrinkles, except sun wrinkles round his eyes when he laughed - which was most of the time. Hair was heaped on his head like a golden halo, and although it looked silky-soft, Vega knew it was so thick you could hardly run your hand through it.

Hector’s arms were spotty, as many old people’s arms are. But there was one spot on his arm that was special. At first glance, it looked like any old birthmark. But if you looked more closely, and upside down, it was a little fuzzy giraffe with no ears. What was extra special about the birthmark was that Vega had one almost exactly the same on her arm. It was a little smaller than Hector’s. ‘‘That’s how we know I’m your grandfather,’ Hector would say, ‘only nutcases like us have such fine markings.’

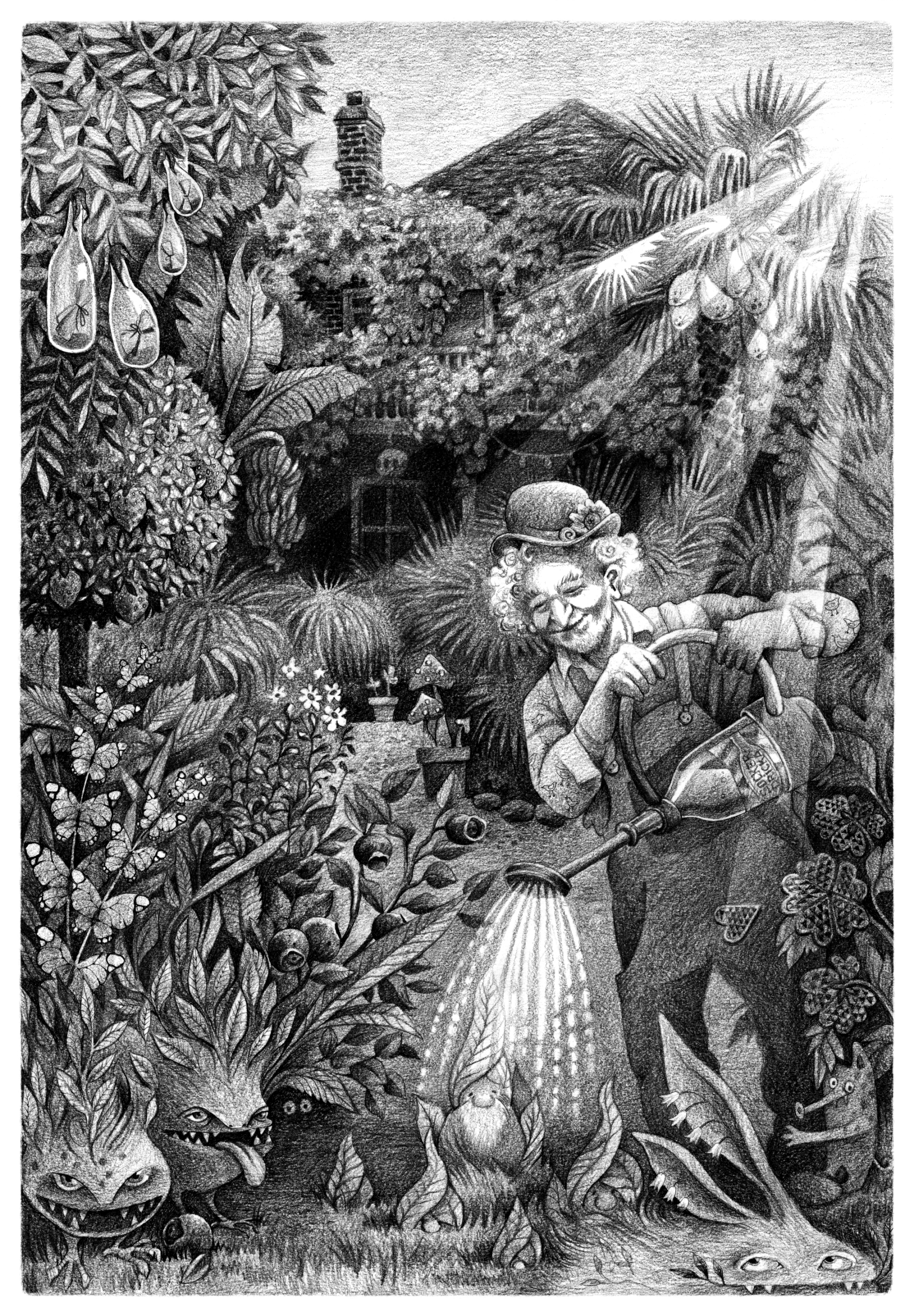

Stepping through the gate in the yellow fence was like stepping into another world; from the mountain’s barren pines and straggly blueberry bushes, into the most luxuriant garden you can imagine.

Hector’s garden was unlikely, and at the same time likely if you knew him. There were blackberry bowers and mango hedges, lilacs and apple blossom, buddleias and fir trees, banana groves and rhododendrons, liquorice ferns and ruby leaves, plankton maples and Dadya trees, and everything bloomed and bore fruit at the same time, always.

Animals lived there too. Very strange animals. There were rabbits with no ears, stripy mice, horses as small as cats and beetles as big as guinea pigs. Not to speak of all the animals that were impossible to describe, like frudbimbles and spoonlurks, fasterers and fourfentipedes. And others with no name, that Vega drew in her sketchbook.

Hector watered the whole garden with lemonade and set out small bowls of juice for the animals.

Hector’s house was in the middle of the garden. From outside, it looked like a flat box. But when it rained, all the surfaces swelled with water, the roof stretched to form a dome, and the topmost white corners of the house grew into towers and pinnacles. Inside the house, the walls shot up and the corners rounded out, spiral staircases grew from nowhere to reach new storeys, with a crisp sound like the cracking of spring ice; all the surfaces were instantly coated in gold and the house became a palace.

‘It’s this confounded humidity,’ Hector complained as he served Vega tea and apple pie on the newly emerged crystal veranda.

When the sun shone, the house took on a completely different form. The walls dried and shrank and large cracks formed. Soon the walls were fissured with gaps and were eventually reduced to a few planks. The roof collapsed and became firewood. In the end, the house looked like a little hut.

‘It’s this confounded drought,’ Hector complained then, and he and Vega stayed out in the garden.

Hector always went about with a wheeled trolley. It had a seat in front, a bit like a kick sled, and a shelf on top. He said it was practical: he could keep small things handy. For example, a roll of tape, an extra light bulb, bandages, throat lozenges, warm socks, and a hat.

‘Life’s too short to run around looking for your hat all the time,’ said Hector, ‘which is why you need a nifty trolley like this to keep it in.’

Hector often had visitors. Several times a day a car would drive up the boring road on the other side of the mountain, and out would hop a couple of keen-eyed figures in white coats.

‘Ah, here are my agents again! Time for the afternoon report,’ said Hector, wheeling his little trolley to the front door.

‘Good day, sir,’ said the white-coated agents. Vega thought it was very smart of the agents to wear white coats. You’d never guess they were agents if you didn’t know.

‘Here we are again. How are things with Hector?’

‘Thanks,’ answered Hector, ‘absolutely excellent as they were last time! And I understand you’re working very hard; I hope you’ve got a little further in your investigation.’

‘Absolutely.’ One of the white coats laughed. ‘You could say that. Has Hector remembered his medicine today?’

‘Ah, my visibility pills! Of course, I took them a moment ago. Before that I wasn’t exactly invisible, but a little blurry round the edges. Come with me so we can prepare your report. Vega, wait here, we’ll be back soon!’

Hector had so much going on. Even though he was old, he could manage various top-secret investigations, look after his fantastic garden with all the animals and at the same time know everything there was to know in the whole world. He knew all the stories and legends about Giraffe Island, and they grew more exciting every time he told them. Sometimes they were about the faceless men who once lived on the outskirts of Capital City, who painted eyes, nose, and mouth on their faces every time they went out. And sometimes about the knight with a green beard who planted the whole forest on Giraffe Island with the hairs of his beard for seedlings. And about Clump Paw, the enormous creature almost impossible to see, but who according to Hector wandered around this very forest. He’d seen where his footprints created great pools in the bog. Sometimes Hector told her about Giraffe’s Heart, which was the most beautiful lake in the whole world. The water in the lake was as sweet as lemonade, but not many people knew it. Giraffe’s Heart was so shallow you could wade across without the water going above your knees, and at the same time so deep that no one had ever found the bottom, Hector said. Sometimes a sea creature and an underwater city appeared in the story. Other times there was nothing living or growing at Giraffe’s Heart, it was like a gigantic bathtub. No one knew for sure, said Hector.

There was no limit to Hector’s knowledge. Vega could ask him anything. Even though it wasn’t always clear what he meant, he always had an answer, and more.

‘Hector?’

‘Yes, small figment of my imagination?’

‘Why is Giraffe Island called that?’

‘Because it looks like a giraffe! Especially if you see it on a map.’

‘But why is it drawn like a giraffe on the map?’

‘Because people who draw maps have special methods to determine what land looks like from above. They send out a large flock of albatrosses, and they can tell the shape of the land by the types of cries they make.’

‘So, albatrosses call out that the island looks like a giraffe?’

‘Exactly. I was involved in an albatross survey once. It was top-level technology. Of course, it works even better with eagles, but we don’t have those here.’

‘What does the mainland look like?’

‘Probably like any old mainland. I think it has the shape of a crooked old lady if I remember rightly. But they only have Great Tits to help with their map work, so who knows what it actually looks like.’

‘Have you ever been there?’

‘Yes, probably, I dare say I have.’

‘Don’t you remember?’

‘Yes, of course I do.’

‘Do you remember my mother then?

‘Oh yes, very well. Hm, let me see, she looked a bit like this.’ Hector pointed to a small, faded picture that hung over the fireplace. It was a photo of a young girl who looked a little like Vega, with dark curly hair and dark eyes looking anxiously at the camera. She was wearing an oversized green coat; the arms covered her hands and the hem trailed on the ground. On her head was a large top hat. Hector always pointed to the photograph when Vega asked about her mother.

‘But Hector, my mother can’t look like that now. That’s just a little girl.’

‘Yes, a little girl, that’s right,’ Hector mumbled. ‘She loved dressing up in my clothes.’

Hector’s eyes glistened and looked past the photograph, past the fireplace, out through the walls and into a world not even Vega could see.

‘But what was she like?’

‘Your mother? Lovely, a very lovely person. But she had a fiery temper, she could flare up like a woodstove when she was small.’

‘But what’s she like now? And where is she?’

‘Good question. Hard to say. Pretty sure the coat fits her better now.’

That was about as far as Vega got when she asked about her mother. It was strange. Hector who knew everything seemed to have forgotten almost everything about her mother.

Vega’s mother was like a paper doll in Vega’s imagination, one she could dress in new clothes and accessories for each new thing she learned about her. But she didn’t know many things, and it was a long time since she’d given the doll a new accessory.

It had been wearing a green coat and top hat for a long time. It also had curly hair, and wings, so it could fly away when it wanted to. Sometimes the wings turned into flames. Hector had said that her mother was fiery. Maybe the paper doll should be a dragon that could breathe fire and fly. A paper kite dragon that could fly way, way up high. Without a string.

They sat in the garden drinking Hector’s homemade honey berry juice. It was warm and sunny, so Hector’s house had shrunk once again to a little hut. There wasn’t much to be done about it, other than to stay out in the garden and hope for a few drops of rain. Vega had gone straight to Hector after school. She knew that her father wouldn’t be home anyway. As usual, these days.

‘Hector?’

‘Yes, small figment of my imagination,’ replied Hector, blowing large pink bubbles of skyberry juice through a straw. They sailed far away through the garden, until a flock of joybells fluttered out of a bush and attacked them. (Joybells can’t actually fly very far, but they love skyberries and bubbles).

‘Dad’s been behaving strangely,’ said Vega.

‘He’s always behaved strangely.’ Hector tickled a passing firefly. ‘At least I’ve never understood what makes that man tick.’

‘No, but it feels as if something has happened. I don’t know what. He’s almost never home, and even when he is, he’s not really there. He hardly listens to anything I say, and he forgets to cook dinner.’

‘Aha! I get it,’ said Hector. ‘He must have had a heart attack! They say it can happen. It makes you all confused and giddy and you forget things.’

‘But he’s not sick, just weird.’

‘Well, that’s exactly what happens with a heart attack. Try to listen to his heartbeat next time you see him. I bet it sounds different than it used to. It might be broken. Kaput!’

Vega thought about her father’s heart, broken into a thousand pieces. If it had broken, it would surely mean more bad luck than breaking a mirror.

‘But how would it have broken?’ she asked.

‘It can break in many different ways. It’s tricksy, the heart. Be glad you’re not an octopus; they have three!’

‘Is that true?’

‘Yes, of course it’s true! It’s actually quite practical, because if you have three hearts, they can take turns being broken and healed. Octopuses must be very happy animals.’

Vega imagined a very happy octopus with three different hearts blinking red, yellow, and green, like traffic lights.

Red meant broken, green meant completely healed, and yellow something in between.

‘Your father may not have three hearts,’ said Hector, ‘as far as we know. But at least he has one, and it’s big. I know that much about your father. He may be strange, but he has a big heart. And if that’s the case, he has to take extra care. A bit like having a huge china shop. In a normal-sized china shop you can keep an eye on everything all the time, but if it’s huge, it’s much harder! Maybe a whole elephant is hiding in the basement. And it’s trampled to pieces your most valuable porcelain bowls, but you don’t know it. You might only find out much later and realise you’ve been broken for ages. Well, you get the logic. It’s exactly the same with your father.’

Sometimes Hector’s logic was too convoluted for Vega. She nodded silently and swallowed a gulp of skyberry juice.

Giraffens hjärta är ovanligt stort

Schildts & Söderströms, 2022, 206 pages.

English edition: Giraffe Island, Gecko Press, 2024 (translated by Julia Marshall).

Foreign rights: Helsinki Literary Agency.

We are grateful to Gecko Press and Helsinki Literary Agency for permission to publish this translated extract.

Winner of the 2022 Finlandia Junior Prize, and nominated for the 2023 Nordic Council's Children and Young People’s Literature Prize and the Runeberg Junior Prize

Sofia Chanfreau and Amanda Chanfreau hail from Åland and currently live in Malmö, Sweden. Giraffens hjärta är ovanligt stort (2022) is the sisters’ debut work. The book is also reviewed by B.J. Woodstein in this issue.

Julia Marshall is a translator and publisher at Gecko Press, a small-by-choice independent publisher of children’s books by the best writers and illustrators in the world, translated into English.