Old Wives’ Meeting

by Elin Wägner

introduced and translated by Sarah Death

Elin Wägner (1882–1949) was a novelist, journalist and ardent campaigner for many causes, from women’s suffrage to pacifism. She was also in the vanguard of environmental awareness.

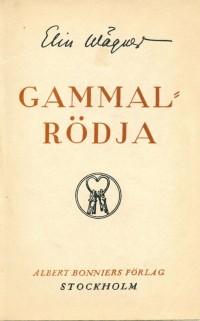

‘Käringamötet’ (Old Wives’ Meeting) is one of the linked short stories in her mid-career collection Gammalrödja: skildring av en bygd som ömsar skinn (Gammalrödja: A Country District Sheds its Skin) published by Albert Bonniers Förlag in 1931. The story was selected in Sweden for inclusion in a recent anthology of the best Swedish short stories from the early nineteenth century to the present day: Ingrid Elam and Jerker Virdborg (eds): Svenska noveller från Almquist till Stoor. Albert Bonniers Förlag, 2018.

The story begins with a disagreement between a clergyman and his wife in a rural parish in the southern Swedish province of Småland. They cannot agree whether, on the morning of the Sabbath, they are justified in pulling up the fishing nets they have set out in the lake the night before. But this is just a prelude to a story that ranges widely over evolving views in society, changing perceptions of women’s roles, and the clashes that inevitably occur between tradition and innovation, faith, superstition and reason.

Old Wives’ Meeting

It is fortunate for a man and wife if their world is divided into two kingdoms. This is becoming increasingly rare, for soon the home will no longer be a kingdom, and will have no need of a queen.

But Gammalrödja vicarage in the Springers’ time was a double kingdom, where each reigned over their own region. On only one point was there a battle of wills. The dean and his wife had long disagreed on the subject of Sunday fishing, and this was not such a trivial matter as one might have thought.

The dean never emptied his nets on Sundays, believing this to be a breach of the Sabbath. As soon as his sons were old enough to have a say, they agreed with their father so that they could sleep undisturbed on Sunday mornings.

The dean’s wife, however, was equally unshakeable in her conviction that the far greater wrong was to leave the fish hanging there in the mesh of the net until Monday morning. The quarrel escalated to become almost a question of philosophy of life. What did the outward form matter for the actual content, the letter for the spirit?

The dean’s wife would always point out that there was a step readily to hand for settling their dispute in a way that respected both their wishes, namely to stop setting out the nets on a Saturday evening.

The dean did not deny that this would be a legitimate solution, and this was just the disagreeable thing about it. For there are certain consequences one cannot induce oneself to accept in this world, even when they offer peace with both one’s conscience and one’s wife, which is otherwise an ideal state of affairs.

For many years the nets were left to lie in the lake untouched from Saturday to Monday, with the fish trapped in them.

The conflict would flare up every year when the ice started to crack and move on Kyrksjö lake. But the first, or perhaps it was the second, year after the bishop’s inspection, the dean’s wife said nothing when her husband rowed out that first Saturday evening. So he thought he had won, and felt a little shamed by the fact.

He was mistaken, however.

On Sunday mornings his wife would get up at half past five after long hours of wakefulness, rouse the maid and take her down to the lake to empty the nets. When the sons of the family came home from college for the holidays, they lost no time in informing their mother that this was cruelty to animals, namely the maid. She was now deprived of the perk of luxuriating in bed until half past six on Sunday mornings. Their mother took the point, and therefore made an arrangement with the Söderbergs’ Sara to come every Sunday morning to row the boat. The Söderbergs did not need her anymore; they had both been dead for fifteen years. Sara was now married to a day labourer, who presumably had a name, but she was still generally known by the name of her former master and mistress and registered no surprise at the fact, for she knew she was a household chattel.

In this capacity she accepted the dean’s wife’s offer, removed the fish from the nets every Sunday and engaged messily with their bloody little entrails without anybody calling that cruelty to animals. This she did with the same dogged persistence with which she washed babies’ nappies, drowned cats for the sensitive, burnt out rats’ nests and beheaded chickens before plucking and drawing them.

No one had any conception of how much Sara’s own guts churned at these revolting operations. People knew how much she needed a meal and a bit of ready money and were happy to provide her with them. When she periodically disappeared round the corner and threw up – from pure disgust – whatever they had fed her, they would remark: poor thing, she’s in the family way again, and no more would be said on the matter.

If anyone had happened to try taking soundings of Sara’s disposition, living its life beneath a silent, grateful surface, they would have discovered her to be in possession of a lively, defiantly resigned soul. She had a view of life that in many respects diverged from the approved one. She did not see life as something absolutely good, nor did she see children as a gift from God. The fact that she constantly produced more babies despite this scepticism was the result of not seeing any alternative. That time when the old midwife was helping her with the eighth baby, she remarked ‘Such a pity to have to get used to a new midwife now.’ The old midwife, emboldened by her imminent retirement, seized the moment to say: ‘I think you should just tell him no, Sara.’ – ‘But he’ll only go to other women.’ – ‘Well let him, then.’ Sara made no reply to that. But a little while later she said: ‘I’ve only got six more years until I turn fifty.’ That was her consolation. She knew that then there would be an end to all this breeding, bearing and giving birth to which she had been consigned by God’s mysterious, all too mysterious ways.

Her last child came into the world when she was forty-nine, so her calculations had proved correct.

But her most tender and heartfelt hope for this baby was that his life would soon be cut short.

That was precisely what she was thinking one enchanting morning as she went out fishing with the dean’s wife again, for the boy was poorly.

The dean’s wife, too, was in excellent spirits.

After a dramatic reckoning with the summer, autumn had settled into the mild magnanimity of the victor. Mrs Springer relished this mildness and felt her own kinship with the day: sunny and cool, slightly faded, completely still and clear.

Her life, too, had reached another season. Her world had closed around her again after contentious ideas had torn holes in its safe and familiar artefacts. Today Marcus would preach for the first time; it was a sign that the younger generation would soon be ready to step in. One could look forward to the end of one’s work, such as it was.

All praise to the Consummator, God alone.

As Mrs Springer leant over the side of the boat to haul up the first net, she found the water to be so clear that she could look right through it to the bottom. There below her she saw a gradually dulling silver glitter of imprisoned lavaret and roach, and thought she could glimpse some perch, too. Poor things, they had swum blithely into the trap and not been able to wriggle free. Resigned and motionless, they hung there tender-gilled in the mesh of the net, like a row of Söderbergs’ Saras.

There was a faint possibility of escape at the very moment they cleared the surface of the water. A real fisherman tries to be nimbler than the fish themselves as he pulls the net over the side of the boat. The dean’s wife, on the other hand, loitered over the task and many a quick flash of silver vanished into the depths when she was in charge. The dean had no way of checking up on her, because he was not there.

The dark, glassy surface of the lake in the morning shadow of the forest was broken by the merry silver splash of the anguished creatures. There were a lot of them today; although some had disappeared into the deep water, large numbers of them were in convulsions in the bottom of the boat.

‘Stun them, Sara,’ said Mrs Springer, and then Sara knew she had to hit them on the head with a stone. She loathed this, but could not extract herself from the net of her fate until death hit her on the head with a stone, too. And no one would ask how long she would have to spend conscious and gasping for breath until then.

Once all the nets had been emptied, the two women rowed home. Sara sat on the rower’s seat with her mouth clamped firmly shut on what little of God’s reward she had been plied with before they set off.

Then the sound of the church bell with its first call to service came floating across the quiet lake.

‘Leave the oars for a minute, Sara,’ said the dean’s wife.

She turned towards the church and whispered:

‘If you move me only gently

slowly

I shall sound when you die.’

It was the promise inscribed into the ore of the smaller of the two bells.

The dean’s wife had tears in her happy eyes as she turned back to Sara.

‘The pastor will do it all right, you know,’ Sara made so bold as to say.

The dean’s wife replied that he was no longer just an ordinary young student, because he had sat his first examination. So he would certainly know what was expected of a sermon. But she still sensed that he was anxious; he had been pacing his room upstairs for half the night, and it was not a good sign.

‘To think of that little lad turning out a teacher,’ said Sara. ‘But you could see it even when he was little, he was so wise. I remember what a grand job he made of his reading at the parish meeting, and how well he knew his catechism and answered the Bible questions. So today I shall go to church, never mind how Sigurd is.’

‘What’s the matter with Sigurd?’

‘Must be teething pains, I reckon. He keeps on turning blue, at any rate. Do you think I’ll have time to get all these roach gutted before the service, Mrs Springer?’

Not without difficulty, the two women manoeuvred their heavy basket of full, wet nets ashore. They had set off up the little lake path towards the road, when Sara suddenly set down the basket.

‘We’d best turn back, Mrs Springer,’ she said urgently.

‘Now what? Whatever’s wrong with you, Sara?’

‘Mrs Springer, surely you can see the young pastor is on his way down here from the house? Master Marcus always comes down to the lake in the mornings.’

‘Sara dear, he won’t eat us. Do please get on with it. He doesn’t mind us fishing on Sundays as long as he doesn’t have to.’

‘Lordy me, Mrs Springer,’ said Sarah in agitation, ‘do you really think we can let him run into old wives the minute he comes out of the house on such an important day? Just think how things might go when he’s there in front of the altar, with him not used to it and all.’

The young preacher clearly had not seen them yet. Sure enough, he was coming down the road towards to the lake, but was walking slowly, head bent, reciting from memory.

‘… Friend, go up higher: then shalt thou have worship in the presence of them that sit at meat with thee.

‘For whosoever exalteth himself shall be abased: and he that humbleth himself shall be exalted.’

The dean’s wife was momentarily speechless with astonishment at Sara, who for the first time in their acquaintance had taken an initiative, for the first time set down a burden without permission.

‘It’s terribly thoughtful of you, Sara,’ she said, ‘but nobody believes in that anymore.’

The moment she said it, she knew it to be presumptuous. What was it she had heard just yesterday about an accident caused by an old wives’ encounter? Oh yes, it was Baron Ramsey Mustcamp and that sprain to his foot, when he went out hunting in spite of having come across three old wives.

‘There isn’t a single man not scared of meeting old wives when he’s got something important planned,’ said Sara. ‘So I think it would be just plain unfair to the pastor for us to go ahead and meet him.’

‘Run then, Sara,’ said the dean’s wife, laughing to show that she was only agreeing with Sara for the fun of it.

‘What good will it do, Mrs Springer,’ said Sara, ‘for me to run if you’re going to meet him anyway?’

The dean’s wife felt a sudden sting to her heart. It had not occurred to her that the same curse would apply to her as to Sara. She was fifteen years older than her hired help but considered that help to be the old woman, not herself.

‘But you must see that I can’t possibly go and meet him on my own with this heavy basket,’ she said heatedly, although not as heatedly as she would have done earlier.

Sara was already on her way back down to the water.

‘But what can we do if he comes down to the lake after us?’ cried the dean’s wife.

‘He’ll never do that,’ answered Sara without turning round.

The dean’s wife fervently wished that Marcus would turn off the road and come down to greet his mother. With that he would well and truly disprove Sara’s notions and show that no old wives could harm him, not even his mother.

For half a minute she did not know what she ought to do. She was torn between her urge to meet Marcus openly and her urge to follow Sara in meek heedlessness of her own wishes. Her very hesitation was unworthy of herself and her enlightened son, and yet… She was discovering that it had not been so easy for Father to forego setting out the nets on Saturday evenings.

Sara was now back at the jetty and kneeling down at the edge of it.

‘Mrs Springer, hurry up and look,’ she called. ‘Here’s that sheet that went missing in the last big wash.’

This was an awkward subject, because Sara had in reality taken that sheet when she was at her wits’ end with her youngest due. But what else could she do?

The dean’s wife had no sooner heard the word sheet than she rushed down to the jetty and dropped to her knees beside Sara. It was not so much for the sheet’s sake, but now she could defend her own actions in removing herself from any risk of bringing her son bad luck.

Yes, there they knelt, those daughters of Blända’s daughters. The Småland women who rode to weddings, girded with their banners and accompanied by music, like queens; who had the same inheritance rights as their brothers and husbands at a time when the rest of Swedish womanhood had to content itself with half; who had their own moots, councils and games and their own farmsteads and castles.

Marcus was now some way down the road to the lake. He raised his eyes and spied through the alder bushes two women, one of whom was his mother. They were kneeling on the jetty, looking down into the water.

Something must have happened to the nets, he thought, instinctively quickening his steps. Marcus was an enlightened young man, no heathen darkness or heathen respect for the magic of old priestesses or wise women attached to him any longer. But even so. Meeting an old wife could have consequences, everybody knew. And as they had not seen him, they could take no offence if he did not interrupt his train of thought to go down and help them with the nets.

‘… just think, my listeners, what disgrace for the wedding guest who must submit to being moved down from the seat of honour, because a more distinguished guest has arrived…’

For that matter, his secular self interjected, now that I come to think of it, there really is no need to underline this appeal for humility at the feast that my well-brought-up listeners have long since taken to heart…

‘But Sara,’ the dean’s wife was saying irritably meanwhile, ‘have you taken leave of your senses? Don’t you recognise the white stone that’s been here by the jetty for as long as anybody can remember? How could you imagine, or expect me to imagine, that this is my sheet?’

‘The pastor’s gone past us now,’ was Sara’s answer.

Käringamötet

First published by Albert Bonniers Förlag in 1931, in the collection Gammalrödja.

Sarah Death would like to thank Flora Death and Solveig Hammarbäck for early readings of this translation.

Elin Wägner (1882–1949) was a prominent and pioneering Swedish writer, journalist, activist and suffragette. She was a member of the Swedish Academy from 1944.

Sarah Death is a translator and editor and lives in north Kent. She enjoys working on texts from a wide range of periods and genres. Her translations range from novels by Fredrika Bremer and Selma Lagerlöf via the letters of Tove Jansson to the latest part of the Girl with the Dragon Tattoo franchise, The Girl in the Eagle’s Talons, written by Karin Smirnoff and published in August 2023. She has also translated Elin Wägner’s classic novel of the Swedish women’s suffrage movement Pennskaftet (1910) which was published by London-based Norvik Press under the title Penwoman in 2009 (new edition 2021).

An article written by Sarah Death about this story was published on the Wägner Society's website in August 2024.