A Tribute to Laurie Thompson

by his friends and colleagues

Tom Geddes

Christine Moore

Marlaine Delargy

Rachel Schröder

Charlotte Garbutt

Annika Lindskog

Catharina Grünbaum

Linda Schenk

Helen Sigeland

Terry Carlbom

Torsten Kälvemark

Irene Scobbie

Peter Graves

Kerstin Abukhanfusa

Rickard Fuchs

Philippe Bouquet

Håkan Nesser

Maria Rejt

Christopher MacLehose

Becky Toyne

Barry Forshaw

Nigel Smith

Ian Hinchliffe

Sarah Death

Laurie Thompson, editor of SBR for twenty years, who died in June 2015, will be remembered for his leading role in the promotion of Swedish literature in the English-speaking world, not forgetting, of course, the significant part he played in introducing British readers to Scandicrime and the ensuing publishing boom. Here some of his friends and colleagues share their personal memories of the very modest man whose outstanding achievements we celebrate.

An obituary appeared in SBR 2015:2.

Laurie Thompson

by Tom Geddes

After teaching Swedish and German at the University College of Wales, Aberystwyth, 1972-1975, Tom Geddes was Head of Scandinavian and subsequently Germanic collections at the British Library, London 1975-1996. He has translated 25 novels and biographies from Swedish, Norwegian and German.

Without Laurie Thompson there would have been no Swedish Book Review. The initial impetus came from Jeremy Franks, who published the journal Swedish Books in Gothenburg from 1979 to 1982, and then offered it to SELTA. In discussions in London with his coordinating editor Jan Ring (now Teeland) the SELTA committee almost rejected the proposal as impractical. The one dissenting voice was Laurie’s: he had been largely instrumental in saving Swedish Studies from impending closure in the University of Wales by effecting the transfer of the subject from Aberystwyth to Lampeter, and as a man who we now realise was ahead of his time, he felt that the journal could boost his new department, not only academically but in what would now be called outreach or public engagement.

Laurie took on the journal in SELTA’s name, transformed its appearance and content and went on to edit it for twenty years, securing funding, commissioning articles, translations, surveys, bibliographies, reviews, always presenting the latest literary output from Sweden and Swedish-speaking Finland in a varied and interesting way, while maintaining and developing a format which made it easily accessible. Only gradually did he enlist help, from his departmental secretary on subscriptions and distribution, from a separate reviews editor, and from guest editors for supplements on individual authors or themes. As university politics and conditions became increasingly fraught, he confessed to enjoying his work on SBR more than university administration. Yet he continued to inspire, and was greatly liked and respected by his colleagues and students. Sardonic and cynical in many ways, he was a stimulating teacher with seriousness of purpose behind a jokey facade. His jocularity often enlivened the pages of SBR – just one erudite example from 1993: to mark SBR’s ‘First decayed’ he composed pastiche ‘readers’ letters’ from none other than Samuel Johnson and August Strindberg. He was adept at injecting an appropriate note of frivolity into any proceedings, in print or in person.

His post-retirement years, after both Lampeter and SBR, devoted to full-time translating and occasional reviewing, showed no diminution of his dedicated work ethos. He would still be at his desk till midnight, answering an email as he laid his current task aside for the day, just as I remember his working hours when I had the privilege of being his colleague for three years in Aberystwyth in the 1970s. His lectures and seminars there were always meticulously planned, his essay-marking assiduous – yet he seemed the most relaxed of men, and was certainly the social engine of the department, always ready to instigate extra-curricular activities to enhance the academic. He was the most hospitable and generous colleague, and my wife Carol and I had great pleasure in returning that hospitality over the many years of his biannual visits to London. He enriched my own SELTA and SBR pursuits as he had my teaching days.

Laurie

by Christine Moore

Christine Moore (née Davies) was Laurie’s first Swedish student at Aberystwyth. After completing her degree in German, she taught languages briefly, had three children and eventually became a piano teacher in the Music Department of the University of Aberdeen.

In 1966 I went off to university in Aberystwyth, where we all had to choose three Part One subjects. I knew I wanted to study French and German and found, unusually, that Swedish was on offer. I signed up enthusiastically, having been reluctant to repeat the same subjects as I had done for A level, and discovered that I was to be the only student on the course. The lecturer was very formal and reserved and I spent many hours sitting opposite him at his desk while he dictated dry and dusty pages of Swedish history. My only textbook was Teach Yourself Swedish.

Not yet an honours-level subject, Swedish in my second year could only be taken as an option on the German course, in amongst the Old Norse and Middle High German – languages long dead! When we all returned to Aberystwyth after the summer vacation in 1967, however, we found a breath of fresh air blowing through the department in the form of Laurie Thompson, who had arrived to teach both German and Swedish. Not only could he speak Swedish fluently, but he had a real live Swedish wife and baby and liked nothing better than to tell us about life in Sweden in the twentieth century. I continued to have some tutorials on my own as I had a head start on those taking the Swedish option. In any case we were a very small class; yet in those days, even in the late 1960s, all was still quite formal. We would never have presumed to call our lecturers by their Christian names and we students remained ‘Miss X’ and ‘Mr Y’ to the end of our degrees. Laurie, however, would refer to us with both our names, and I remember feeling that here was a human being who realised that we were still only very young adults who needed some warmth in our lives. One incident which revealed his humanity came after our finals, when two of us went to Laurie’s home to help in the garden and were treated to tea (maybe even a glass of wine, though that seems unlikely); my friend felt sure it was a gesture to cheer her up since she had not, as we were all aware, got the degree she deserved. We were to dig up some rampant wild strawberries and these same strawberries still survive, forty-five years later, at my daughter’s home in Cambridge, having first taken up residence in my parents’ garden.

Laurie was always concerned to keep in touch and visited me and my young family two or three times, when he had to travel to Aberdeen for conferences or examining in the department of Scandinavian Studies. He was enthusiastic about a trip which we were planning to South Africa in 2001 and gave us a lot of helpful advice. From his later letters it was clear how much he missed travelling, though he blamed having to look after the cats, rather than his illness!

He remained a wonderfully faithful correspondent, sending us two Christmas cards in December 2014 after we had made one or two slightly complicated house moves, just to ensure that he found us. His letters and emails all reflect his droll sense of humour and love of wordplay, my favourite referring to the doctors at the ‘Horsepickle’ in Swansea, despite the grim reason for his being there.

This quietly caring man who made gentle fun of all things British, Scandinavian and Germanic and who loved language, has been present in my life for close to fifty years. His translations of Swedish detective fiction are on our bookshelves, his last email in my computer and, even though it is many years since we last met, I will miss him – the richer for having known him, the poorer for his passing.

Not Bad At All

by Marlaine Delargy

Marlaine Delargy is now a full time translator, working to keep her four cats in the manner to which they have become accustomed.

I have lost count of the number of times I have sat down to write this tribute and either given up in despair, or deleted what I have written, infuriated by my inability to capture a relationship that lasted for forty-three years in a few hundred words. I almost abandoned the task altogether, but the thought of how unimpressed Laurie would be by my failure to deliver a decent piece of writing, meticulously checked and on time, has kept me going.

I first met Laurie at UCW Aberystwyth in October 1972, where I was planning to do a degree in French and German. After a few weeks it became clear that choosing American Studies as my third subject wasn’t such a good idea; fortunately one of my fellow students suggested that I should go and see Mr Thompson to ask if I could change to Swedish, ‘because it was good fun’. I approached Mr T with some trepidation; it was already clear that he didn’t suffer fools gladly.

‘Do you pick things up quickly?’

‘Errm . . . I don’t know.’

‘Everybody else has already covered a significant amount of ground – you’d have to work VERY HARD.’

I think I managed an unintelligible squeak (he was quite daunting in those days), and he agreed to give it a go. He then spent hours working with me on a one-to-one basis, going over everything I’d missed. His pride and joy was the language lab, with the vast array of tapes he’d produced to accompany and expand the Learn Swedish course. Occasionally I would earn a brief nod of acknowledgement if he found me in there at some odd hour, determined to catch up; I had already fallen in love with the language, the history, the short stories we had started to read.

At Christmas I did the same exam as everyone else, but with little confidence that I had done well enough to be allowed to continue. On the last day of term I bumped into Mr Thompson in town; he gave me one of those brief nods, and kept on walking. Then he stopped and turned back.

‘By the way, your Swedish exam – not bad at all.’

Anyone who knows Laurie will be aware that this was high praise indeed. It was all the encouragement I needed; I did my degree in Swedish and German, and have never regretted that decision for a second. Incidentally, that fellow student now spends every summer at his cottage in Sweden, and had a translation published in SBR a couple of years ago – Laurie’s influence was far-reaching.

Fast forward ten years: I had spent some time in Sweden and Hull, worked with Laurie for two years as tutor in German and Swedish at UCW, taught English in Finland for a year, then returned to Aberystwyth to pursue a glittering career in a greengrocer’s shop. (It’s not as bad as it sounds – we sold tropical fish as well.) One day he came to see me; he was starting up a new journal called Swedish Book Review. Did I fancy translating a short story by Ivar Lo-Johansson? Definitely! I happily bashed away at my typewriter, and a few days after I’d handed it over, he rang me up: could we meet to have a chat about the translation? He started off by saying one or two positive things about the style and tone before pointing out a few improvements that I might like to consider. Then things took a turn for the worse. ‘However,’ he said. I knew him well enough by this stage to realise that this wasn’t a good sign. The presentation, he informed me, was appalling. Admittedly it was covered in Tipp-ex . . . and a few things might have been crossed out . . . and there was the odd arrow indicating that something needed to be moved . . . (To paraphrase Eric Morecambe, I had all the right words, but not necessarily in the right order.) Had I, he wondered, proofread it? Errm . . . not really. Did I know how to proofread? Errm . . . not really. He explained at length and in detail, then gave me back the offending piece. ‘I’d like a clean copy, please, and don’t ever submit anything that looks like that again.’

The advent of computers meant that my life was no longer littered with the powdery residue of dried-up Tipp-ex, but I never forgot the lesson I learned that day: inaccuracy and sloppiness are never acceptable, and only your best is good enough. I did many translations for Laurie over the years, and it is entirely thanks to him that I am about to start translating my thirty-fifth novel; he led by example in so many ways. When I left teaching in 2004, he was endlessly supportive and helpful, putting me in touch with Swedish literary agents and giving advice on contracts, fees, dictionaries and reference books; he was as generous as ever with his time and his expertise.

Over the years we became close friends, emailing on a daily basis and bonding over our love of cats and wildlife, among other things. It is his humour that I miss the most – those caustic comments about some ‘daft’ pursuit of mine, his ironic take on a news story or the frustrations of everyday life, his criticism of the ‘awful’ BBC, an irate account of his dealings with some hapless copyeditor. From the very start he never missed an opportunity to trade insults; we were from opposite sides of the Pennines, so there was no shortage of ammunition. We could always make each other smile, even in the darkest times.

Laurie’s courage, determination to Keep Buggering On, and his refusal to complain over the past five years have been . . . I was going to say awe-inspiring, but I can hear him snorting in derision. He was an outstanding teacher (another snort), the best colleague and mentor anyone could wish for, and above all a much-loved friend. Like so many others I am lost without him, but so grateful to have known him.

Thanks for everything, Laurie.

LTh . . . Actions and Words

by Rachel Schröder

Rachel Schröder studied Swedish in the 1980s at SDUC and went on to do an MA in Guildford before becoming a translator. She moved back to Lampeter in the 1990s to teach translation and became a firm friend of the Thompsons. Her friendship with Laurie was both longstanding and precious.

Laurie was my lecturer, colleague, friend, cheerleader and champion. He was also, as my children will tell you, a cat-lover, magpie-tamer, hedgehog-rescuer and puller of the best silly faces when I wasn’t looking.

Animal and face-pulling antics aside, there was more to The Amazing Laurie Thompson than met the eye. We have heard how hard he worked, how well he taught and how popular he was; however, little has been said of late about the great results that he got with non-academic students. Lampeter was famous as the university of last resort back in the days of unis and polys. Bad results? Go to a polytechnic over your dead body? Then head for Saint David’s University College in Lampeter through clearing! And that was the thing, there were a fair few students with average to poor A-levels tucked away in this particular corner of West Wales. Some of whom had been struggling with personal issues too. But that didn’t deter the Thompsons – the Swedish Unit managed to get the best out of pretty much everyone, not just the bright young things who actually chose to come to the back of beyond. It consistently produced remarkable results and launched a battery of graduates into translation and other careers. While this was common knowledge in the 1980s and 1990s it seems to have fallen by the wayside in recent times.

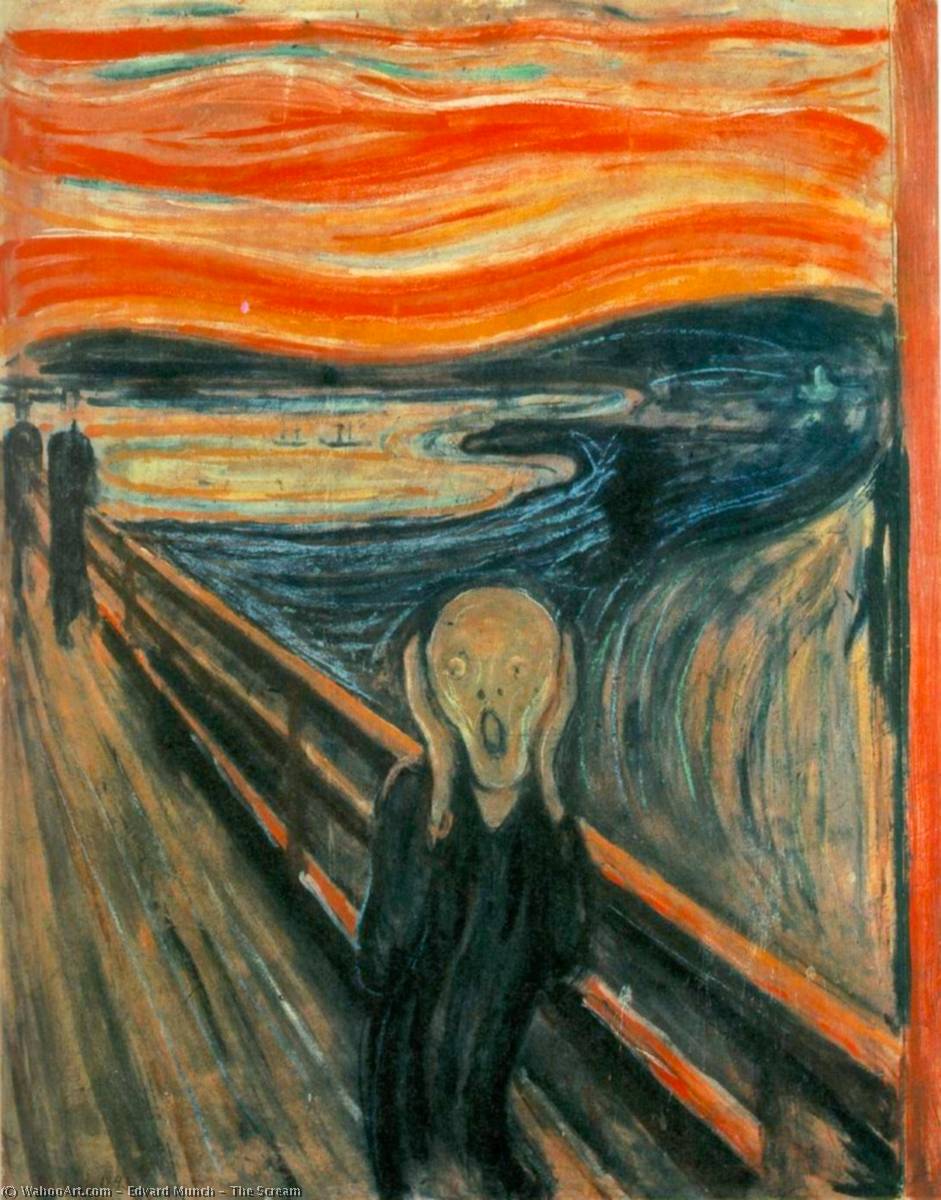

Although I was one of the few who actively opted into SDUC, I struggled towards the very end and would skip off to Aberystwyth at every opportunity. The urge to flee ultimately clashed with one of Laurie’s seminars, so I left him a neurotic and rather hysterical note along the lines of: ‘I can’t take it any more, I’m running away to Aberystwyth.’ But here’s another thing: he had a great sense of humour and took it all in his stride. Whereas the French Department had fired off a warning for a missed language lab session in my first year, Laurie jumped the other way and sent me a card of Munch’s The Scream along with some consoling words.

I actually laughed out loud – times were tough in Rachel World and he sent me The Scream, how cool is that?!

Skip forward twenty-odd years and I am diagnosed as poorly, really poorly. I can’t keep telling people what’s wrong because I cry and that’s awkward all round. So I take to the email. I send Laurie a message headed ‘Brace yourself’. Again he comes back with the unexpected: the Thompsons are upset to the core, they have taken me into their hearts and I have been upgraded from friend to ‘a sort of surrogate daughter’. The man who gave me ‘64%, not bad’ time after time in the 1980s went on to list my strengths and convince me that I was more than capable of dealing with whatever lay ahead. He also wanted me to know that if there was anything they could do, anything at all, just say the word . . . in fact, all I needed to do was ‘squeak’.

My treatment schedule spans months not weeks and I need people to drive me the 100-mile round-trip to Swansea. I recruit Laurie who, ever the thoughtful friend/surrogate father, not only gets me there and back but also produces a rather fabulous lunch to keep us going. As my real dad would say, actions speak louder than words.

But in Laurie’s case it was actions and words. Nobody showed a greater interest than he in how far I’d walked/swum/run on my mission to get well and stay there. Nobody was as quick to enquire after my health or tell me just how well I was looking. And, in the event, nobody has come close to filling that gap since early June last year.

LTh – friend, surrogate father, cheerleader and champion, to say nothing of animal-lover, career-launcher and man of humour, silly faces, actions and words. What a loss.

Memories of Laurie

by Charlotte Garbutt

Whilst a PhD student under Laurie, Charlotte Garbutt (née Whittingham) was assistant editor of Swedish Book Review from 1992 to 1993. After she left Lampeter in 1994 she worked as a lecturer in Scandinavian Studies at the University of Hull, where she now works as a lecturer in Teacher Education.

When I was invited to write this tribute, I decided to carry out a search on my computer for ‘Laurie’. What I found was a piece of Spanish homework I did a couple of years ago when I was learning Spanish. We must have been asked to write about a person who was important to us and, looking back, I was pleased to recall that Laurie had quickly sprung to mind as someone fitting that description. In my feeble Spanish I had written about a lecturer living in Wales who’d written a book about Stig Dagerman, but also about a man who was ‘intelligent, interesting and funny’ and who had made his lectures and classes informative and entertaining. I had even managed a sentence about his cats. Whilst my hundred-word homework – like this tribute – by no means did justice to the mentor, teacher, boss, colleague and friend who was the Laurie Thompson I knew, it seems to have touched upon some of the essentials, I suppose.

My Spanish homework might just as well have been entitled ‘someone who has influenced you greatly’. I would not be where I am today, both literally and figuratively, without Laurie Thompson. I first met Laurie when, as a shy seventeen-year-old, I came to Lampeter for an Open Day – or rather a weekend, because of the journey times to get to the beautiful but somewhat remote Welsh market town where the Thompsons worked. I had applied to Lampeter to read English literature but because the University of Wales required students to study three subjects in their first year, I went along with a friend of mine to a Swedish taster session. There was academic method in my madness, as I was doing languages at A level, but I have to admit that my friend and I were influenced by our penchant for Swedish tennis players, so I went along without much real thought of continuing with Swedish beyond the hour, perhaps, we were to have with Laurie. It would be another nine years, however, before I took my leave, as a student with a BA in Swedish and English literature and a PhD in Swedish literature, of Laurie and of Lampeter.

If the reason I had idly wandered into Laurie’s Swedish taster class was a frivolous one, the reason I chose to change programme to a joint honours degree with Swedish was because of Laurie’s personality and his abilities as a teacher. Whilst I can no longer remember what Laurie covered or what he talked about on that first occasion, I do recall how readily his own enthusiasm for his subject was transmitted to his students. His vast yet understated knowledge, his passion for Swedish literature and culture and most definitely his never-failing wry humour meant that I for one would sit enthralled whilst he went off at interesting and often hilarious tangents. Etched, for instance, into my memory are his references to the Swedish soft porn film I Am Curious (Yellow) and his not infrequent bursts into snippets of ‘You think you’re beautiful but I don’t think so’ (Du tycker du är vacker, men det tycker inte jag). And I can’t for the world forget how he made a derogatory comment during a history session about Sweden’s then Prime Minister Olof Palme only days before the latter’s assassination, but thought to talk us through his alibi when he met us the following week. Over the four years of our degree programme, it contributed to the sense of a warm family atmosphere in the department to be occasional witnesses to the interactions between the husband-and-wife team who taught us, not least on the occasion when Laurie failed to turn up to a class and we could hear Birgitta on the phone in her office, taking him to task in a manner befitting only a wife.

At Laurie’s funeral, Peter Graves talked about the visits the Lampeter Swedish Unit made to Gregynog, the house owned by the University and resplendent in its acres of grounds near Newtown. For a student, it was wonderful not only to go somewhere with seemingly never-ending supplies of delicious homemade cakes in the panelled library, but to have a chance to listen to speakers such as the acclaimed literary translator, Joan Tate. One of the endearing things about Laurie was his bluff but entirely genuine refusal to make any claims about himself, and he also had a way of bringing other speakers down from their ivory towers or sense of self-importance. In this vein, Laurie would be more than happy to know that an enduring memory of the Gregynog days is nothing to do with the content of any of his own sessions, but is the image I had as I looked back from the coach about to leave Lampeter, of the Thompsons’ brown Saab, standing there with its doors wide open, about to be abandoned for two or three days!

I am eternally grateful to both Laurie and Birgitta for extending my days of Swedish in Wales through enabling me to do my PhD with them in Lampeter. It was a very happy period still to walk the narrow corridors of the Arts building, passing Laurie who often gave just a movement of his expressive eyebrows by way of a greeting. And although the funding of something as expensive as a PhD came chiefly from my ever-generous parents and partially from the Swedish Institute, Laurie was always adept at finding new ways to earn me money. By the time I left Lampeter in 1994 I had part-time fingers in various pies such as assistant editor to the Swedish Book Review, international officer and part-time lecturer in Lampeter and in Swansea. I find it very fitting that by sharing these memories of Laurie, a man who was always so significant in my life, I am renewing my own association with SBR.

We are fortunate that Laurie has left such a legacy in his translations and other publications. My husband is now learning Swedish, using Laurie and Birgitta’s excellent Lampeter Swedish, so I come home to mark exercises and essays which were once set and marked by the Thompsons, and I am (re-) reading all Laurie’s translations of Swedish crime novels. If I could change the words of ‘You think you’re beautiful, but I don’t think so’ to describe Laurie, they might be: ‘You didn’t think you were special, but we think so’.

Learning Lessons in Lampeter

by Annika Lindskog

After her time at Lampeter, Annika Lindskog went on to teach in Belgrade and Dublin, before taking up her present position as Lecturer in Swedish at UCL.

‘From Sweden? Aren’t you the weird ones who put candles in your hair before Christmas? They do that at our university at home.’ Still in the middle of our university degrees at Umeå University, we had decamped to Germany (Würzburg) for one of those exchange years, in order to learn German. Which we did. But we also learnt something else: we discovered that at other universities, outside Sweden, people were learning Swedish. This would – quite literally – change our lives.

Back home, we discovered that the university where Swedishness was defined by Lucia traditions had links with our own. Not that we had ever heard of a place called Lampeter; I am not even sure that we could have said anything at all about Wales with any confidence. But this seemed entirely immaterial – it only mattered that there was a university out there prepared to take on untrained and (almost) completely inexperienced graduates who were curious about teaching and learning Swedish as a foreign language.

Laurie and Birgitta Thompson thus became my very first teacher-trainers. Without them I might not have been teaching today. Or at the very least not in the same way. Twenty years on, and our favourite translation exercises remain Laurie’s. Well, I can’t say for certain who wrote what, but when the protagonist turns out to come from Nether Heckmondwhistle, I think we can safely assume . . . The parameters and aims of translation exercises in language learning were also learnt in Lampeter, and new translation exercises at UCL today continue to make up stories with as many grammatical traps as each sentence can take for the intermediate level, and strive to find authentic texts on relevant topics in rich and challenging language for the advanced students. For the early levels Laurie and Birgitta also produced ‘readers’: authentic texts in Swedish with long wordlists and content exercises. My intermediate students to this day take Söderberg’s ‘Pälsen’ and Bargum’s ‘Bonnie’ home with them for Christmas. It makes them a bit depressed admittedly, but that is a small price to pay for cultural language contextualisation.

And then there was Lampeter Swedish. When we taught our very first Swedish lesson back in Würzburg, there was very little material available, and none which satisfactorily covered all aspects of a beginners’ course. So in Lampeter they made their own. Basing their content on Learn Swedish, originally published by the Institute for English-Speaking Students at the University of Stockholm, Laurie and Birgitta created a structured and pedagogical set of lessons that were both easy to follow and continuously challenging to the learner. The copy I still own is the third revised edition from 1992; the first was published in 1989 (‘Designed and typeset by Laurie Thompson using Pagemaker4 and a Macintosh IIsi computer’!). Occasional features give away its distinguished age: in the first text, for example, we meet herr Gustafsson and fröken Ström, in the chapter on rooms, the advert offers a flat by Hötorget in Stockholm for SEK700 (!), and when Sven watches TV in Unit 7 and upsets his wife, it is because he likes a film with Raquel Welch . . .

But the structure is eternally sound. Every unit starts with a text designed around particular vocabulary and grammar, with a vocab list attached for easier understanding. This is followed by essential grammar explanations, written exercises that get steadily more complicated until they become full translation sentences, an additional text or texts with questions and more translation sentences, then a further ‘reading passage’, and at last, a final essay. Everything the student needs is here, provided in logical, bite-sized chunks and steps, allowing for adaptation to individual learning speeds (or energy).

And it was local. For English-speaking learners Swedish was always quite poorly provided for - there was, for example, no comprehensive grammar of Swedish in English until I started teaching in Belgrade in 1996/97. Lampeter Swedish not only approached the new language from an English linguistic perspective, but had also been tailor-made for British university study. The units – 22 in total – matched the weeks available for teacher-led study, the dedicated focus in each chapter on particular aspects made it perfect for the long month of student self-revision at the end of the course, and the extra texts and reading provided useful material to expand with – or return to later. And in addition, it understands its students. It asks them to write an essay describing their room in College in Unit 3; Unit 6, on giving directions, has a young lady being lost outside the Black Lion in Lampeter; and the students in the text examples are often seen flying between Lampeter and Umeå, or commenting on how much they enjoy learning Swedish and how easy it is . . .

Simultaneously thus locally adapted, but still universally and firmly Swedish in outlook, Lampeter Swedish gave the students the best possible tool to start mastering this new language. Laurie and Birgitta have been both indispensable and groundbreaking for Swedish learners and teachers, and their methods and materials will live on in new users. For me they were not only incredibly caring and friendly bosses, but also invaluable as mentors and models. And they once made me the proud owner of a DAF 55 – like so much else, a unique and educational experience that could only have come from the champions of Sweden in Wales.

Thank you both.

A Truly Remarkable Friend

by Catharina Grünbaum

When Catharina Grünbaum met Laurie she was working as a linguist at the Swedish Language Council. She went on to be the ‘linguistic watchdog’ at Dagens Nyheter. Today, retired, she continues to write about language and usage and edits the Bellman Society members’ magazine.

Of course I have been familiar with the concept of British wit for most of my life, in literature, on the stage and in BBC programmes, but until I met Laurie Thompson I had never encountered it in a living person.

When, in April 1985, I was invited to a Scandinavian Studies conference in Lampeter run by Laurie, we instantly became friends. Laurie later came to Stockholm, where he stayed in the guest apartment of the Swedish Writers’ Union in Strindberg’s Blå Tornet. We met now and then, and spent several late nights lambasting, with the benefit of Laurie’s dry eloquence, some of Sweden’s more pretentious cultural figures. The odd tot of whisky might have fuelled inspiration. On most things we were in agreement, with the exception of Astrid Lindgren. Pippi Longstocking was not to his liking.

‘That old rag,’ Laurie said sarcastically, when I left the Swedish Language Council to be the language consultant on the leading daily newspaper, Dagens Nyheter. How could I stoop so low? That old rag, however, gave me the opportunity to write columns on language and linguistic guidance, which Laurie enthusiastically passed on in Swedish Book Review. His humour was not just ironic, it could also be warm.

Twenty years later, when I was writing a book of an entirely different kind, Från sluss till sluss (‘From Lock to Lock’), containing impressions of French canal trips over a period of some years, I often had Laurie in mind as the imaginary reader, as if in a continuation of our correspondence. I knew that certain turns of phrase would appeal to him. Laurie later undertook (for far too modest a fee) to translate a number of chapters in the hope that a British publisher might bite. He was sceptical – not because of the quality, but because he thought it was futile by and large to attempt to get anything from Swedish published, other than crime fiction. Unfortunately, he was right.

However, my husband and I had a little edition of the translated sections printed, and we have given them to sympathetic English-speaking boaters we have met on the French waterways. It has been a minor success, primarily because of the language, which above all captures the British taste for the myriad eccentricities of French canal life. I cannot thank Laurie enough for that.

It is always both enjoyable and productive to discuss translation problems with skilled translators, and this was very much the case with Laurie. I was able to quell his initial horror at the technical terminology in the art of operating a lock, by promptly supplying a list of English terms. After that, we could concentrate on the subtleties.

We lamented then, and regret still today, that no publisher asked Laurie to translate the whole book. He thought it would have been more fun than having to contend with the many technical and official documents he took on between the novels and whodunits. And when I heard reports in recent years of how he hard he was working, I was dismayed. His condition was serious, and his familiar closing words ‘Time to put him to bed’ (the hour already very late) showed that he was working too hard.

Sadly, there would be no visit to Laurie and Birgitta in Wales – work, family, canal life would intervene. But we did meet, all the same, at an academic conference in Colorado and for several consecutive years at the book fair in Gothenburg. A look or a raised eyebrow was all that was needed, when something was just too stupid, or too boring, or too pompous.

I also have Laurie to thank for introducing me to the writing of David Lodge, whose satirical campus novels we sometimes alluded to in our letters, when we were describing absurdities in professional life or some nonsense in the arts.

Corresponding with Laurie was a joy. Nothing is as encouraging as a counterpart you know enjoys your style, and we could both give our best shot, Laurie in English and I in Swedish. But we could also dispense with stylistic devices, and write about things close to us, about cats and gardens and daily concerns. Others have written about the immensely important role Laurie played in promoting Swedish literature to both the general public and to university students. For myself, I miss the sarcasm and warmth of a truly remarkable friend.

Translated by Deborah Bragan-Turner

Life Comes Full Circle

by Linda Schenck

Linda Schenck moved from the US to Sweden in the 1970s. Following a career as a conference interpreter and accredited translator, Linda now focuses on literary translation and is a regular contributor to SBR.

I became acquainted with Laurie in the early 1980s, when Swedish Book Review was in its infancy, here in Gothenburg, where I live. At the time I was merely an enthusiastic fledgling translator based in Sweden. Fortunately, in spite of my US roots, Laurie and the other UK translators from Swedish who were a generation older, Mary Sandbach and Joan Tate, welcomed me and advised me. This was in the days before email, when letters to the US took a week in either direction and telephone calls were very costly, making communication with other American translators difficult. Laurie soon began encouraging me to participate in Lampeter’s Translator in Residence scheme, which entailed spending a month there, mainly to work on my own translations (with the door open so students could drop in), and holding a weekly seminar for the students who were studying Swedish. I did so in winter 1986, and had a wonderful and productive work month, as well as spending a good deal of time with Birgitta and Laurie, cementing our friendship.

Somehow, that was all thirty years ago. Since then our paths have crossed more or less annually, often in Sweden at book fair time, but also in both Llanybydder (most recently in October 2014) and elsewhere. At some point Laurie became a ‘retired country gentleman’, which meant devoting himself at least full-time to Swedish Book Review and translation. In recent years, emails would often arrive from Laurie written late in the evening when, I imagined, he finally decided it was justifiable to stop working for the day. They often concluded with ‘Dags att lägga honom’ (Time to put him to bed) and a signature. And somehow I have now become a member of the older generation of translators. Mary and Joan are long gone and now Laurie, too. I puzzle often over the question of what a life is, and look back at theirs with gratitude and admiration. Laurie is already greatly missed.

When Laurie was Given a Hat

by Helen Sigeland

The first time I met Laurie was probably at a conference of Scandinavian Studies teachers, held at the University of Surrey in 1983. Little did I know then that he would become my friend and professional contact for more than thirty years. A few years after that first meeting, I visited Laurie and Birgitta in Lampeter with Christer Knuthammar, then dean of Linköping University. In 1986 Laurie had been awarded the degree of Doctor honoris causa at Linköping and there, in the midst of all the pomp and ceremony, amply provided with fine lunches and elegant dinners, in formal dress, he had been presented with his doctor’s ring, diploma and laurel. The only thing still missing was the hat, but of this Laurie was blissfully unaware.

The reason for the visit to Lampeter was the student exchange with Linköping that Laurie had initiated. I don’t recall now if the occasion was the official signing, but St David’s University College in Lampeter had invited us to a grand banquet with dignitaries from inside and outside the university, and here, unbeknown to Laurie, he was to receive his black doctoral hat as a gift from Linköping. Birgitta had been assigned the challenging, not to say impossible, clandestine mission of measuring Laurie’s head, so that the hat was the right size. Laurie was not known as a wearer of hats, so how Birgitta managed to carry out her task, I have no idea.

The next problem was on the evening itself – smuggling the bag containing the rather large hat-box into the hall without attracting Laurie’s attention. His eagle-eye naturally went straight to the bag and everyone who ever met Laurie will be able to picture the raised eyebrows and surprised expression. ‘Do you intend to stay for the night?’ was all he said. No, I said, but I’m wearing new shoes and I might need to change them during the meal. The look he gave me in response was indescribable. And, of course, I couldn’t explain why I didn’t change my shoes there and then; it would have been both logical and practical, as he made quite clear.

The dinner was wonderful. Laurie was presented with his hat and fitting tribute was paid in many long speeches. Had the object of the celebration been someone else, Laurie would have written a ‘daily report’ that night, signed ‘The Ghost of Stig Dagerman’, and delivered it the next day. He was a master of praise for those around him, but extolling his own virtues was alien to him. Did he ever wear the hat? I doubt it. But we enjoyed giving it to him. And he deserved it.

Translated by Deborah Bragan-Turner

Laurie Thompson In Memoriam

by Terry Carlbom

Terry Carlbom, PhD, was Swedish cultural attaché in London 1979-1983. He returned to Uppsala University as teacher of Political Science. Twice lord mayor of Uppsala (Lib), and later also twice mayor of the township of Knivsta, he was secretary general of International PEN (London) 1998-2004.

It is a tribute to Laurie in itself: the recurring themes of lifelong friendships, the helping hand, gentle humour and an air of quiet dignity all of us seem to associate with Laurie. What made him special indeed was his ability to match a sense of purpose with a grain of Attic salt.

I met Laurie shortly after I arrived as cultural attaché to the Swedish Embassy late in 1979. Reviewing the days of PM Margaret Thatcher, spending on culture was not her main priority. Demand for funding was high, but protocol generally required a quid pro quo which was often not forthcoming. Literature, though, had a helping hand through the Anglo-Swedish Literary Foundation. This was originally created by G. B. Shaw’s Nobel Prize money – the prize was finally accepted by G.B.S. on the condition he would be allowed to give it away!

Anyhow, contemporary Swedish politics at the time were ‘organisation-friendly’. It was much easier to fund an organisation than to fund individuals. So the idea arose that this prime but very small group of individuals who were authoritative Swedish-English literary translators should be invited to form an organisation, which at least could be given assistance as a professional network. Reminding ourselves, of course, that translators can be as individualistic as authors, this would only work if an underlying sense of community was going to make it possible.

The story of SELTA has been noted elsewhere, but in this marvellous group of classic names concerned with translation, constructive attitudes like Laurie’s prevailed, and SELTA – and Swedish Book Review – lives on. To this, I would like to add the network of Anglo-Scandinavian Societies, and of course, those universities which, for as long as possible, proudly maintained Scandinavian departments of language and literature. Any deeper insights on my own part into the wonders of intricate translation stem from these days. Only with exceptional empathy is quality ever achieved. This was Laurie’s realm of excellence.

Once a friend, always a friend. In his unassuming devotion to family and friends, his endearingly lovely and humorous correspondence, Laurie cultivated the art of Attic salt to perfection. A great man of letters and an exceptionally charming humanist has gifted us with many a heart-warming memory to treasure in days to come. We will indeed miss the wit and wisdom of Laurie Thompson.

Memories of Laurie

by Torsten Kälvemark

After his time as cultural attaché in London, Torsten Kälvemark returned to Stockholm to work in higher education.

My memories of Laurie Thompson are to a large extent associated with Gregynog, the spectacular conference centre of the University of Wales. For many years Laurie and Birgitta arranged Svenska dagar (Swedish days) there, offering their students from Lampeter an impressive programme of lectures and discussions around all things Swedish.

During my time as cultural attaché at the Swedish Embassy in London (1989-1992), I was invited there every year to give a talk on current cultural or political issues in Sweden. Even after my return to Stockholm I couldn’t say no to the invitation to attend yet again.

What made me love Gregynog and its temporary visitors was the warm atmosphere created by Laurie and Birgitta. It was amazing how they had managed to recruit so many gifted young people to study a minor European language. Of course, the students had their own special reasons for wanting to learn Swedish. One had a boyfriend from the country, another a Swedish mother. Some wanted to learn the language of ABBA, others had read books by Astrid Lindgren. A frequent reply, when I asked them about their choice of subject, was the reputation of the Swedish department at St David’s University College in Lampeter. They had heard about an academic environment where the modern concept of ‘excellence in teaching’ was put into practice.

I was joined on these occasions by other external lecturers. I can’t name them all but I remember Joan Tate speaking about the art of translating, based on her own personal history of being stranded in Sweden during the war, thus obliged to learn the language. I can also recall how Peter Graves gave me new insights in his lecture on the popularity of strong Swedish navvies in the building of railways.

Equally memorable were the evenings in the bar where we gathered around glasses of whisky or beer. Laurie was usually presiding at one end of the table, entertaining us with his dry wit and good humour. We withdrew to our beds quite late, expecting ghosts to appear in the old manor at night, but they never materialised. In the morning we were offered the full English (or Welsh) breakfast with baked beans and fried tomatoes, always a bit peculiar as a morning meal for a Swede.

Apart from these wonderful days at Gregynog, I had the opportunity to meet Laurie and Birgitta on other occasions. I visited Lampeter and could see for myself the academic premises in the small and idyllic town surrounded by green hills. Laurie was of course also present when SELTA had meetings in London and I have a number of entries in my guestbook from receptions after those meetings.

I must confess that I played my own small part in the royal decision to award him the Order of the Polar Star for services to Swedish literature and culture in 1992. The distinction was already well deserved then, but it was even more so in the light of his subsequent prolific work as a translator, from the first Henning Mankell crime novel in the late 1990s, to his translations of Mikael Niemi, Åke Edwardson, Håkan Nesser and others. One can’t but admire his working capacity and endurance in producing so many good translations, paving the way for the success of Nordic crime fiction in the English-speaking world.

I met a lot of interesting people during my time at the Swedish Embassy in London but Laurie was the person with whom I really remained in contact over the years. He usually sent me a letter before Christmas summarising important events during the past year. I sent a letter back or phoned him. We compared notes about developments in Sweden and Britain. His view of domestic or world affairs was a bit more pessimistic than mine, but his complaints about various politicians or the quality of higher education were always tempered by his humour.

We used old-fashioned means of communication like letters or phone calls. In my archive I can find only one single email from Laurie. It’s dated New Year’s Eve 2007, written in a mix of Swedish and English: ‘I’m very busy finishing off the finslipning of Nesser’s Kvinna med födelsemärke, which has to be submitted after the holidays. (Håkan has received the first half, and claims to be more than satisfied – alltid något.) Back to the grindstone – och allt gott för 2008!’

The email is signed ‘Hal E. Lujah’.

I won’t receive any more letters from Mr Lujah. Nor will there be any more telephone conversations with Laurie Thompson. I will really miss a long friendship that was based more on kindred spirits than on the frequency of contacts.

Dr Laurie Arthur Thompson

by Irene Scobbie

Irene Scobbie, former Reader in Scandinavian Studies, taught Swedish at the University of Cambridge, before heading the department of Scandinavian Studies at the University of Aberdeen and then the University of Edinburgh. Since her retirement she has continued to write and translate.

Laurie Thompson and I both came to Swedish via German studies, and for several years we ran ‘small’ language departments in the ‘Abers’ – Aberystwyth and Aberdeen.

For a number of years Laurie was our external examiner and we were able to appreciate his expertise and fair-mindedness when assessing our students. I also remember his characteristic expression, a combination of exasperation, resignation and wry humour, when we mislaid our departmental calculator and were grappling with mental arithmetic in our final calculations. His domestic skills and lack of pomposity were in evidence one year when I had an injured thumb and he ended up doing the washing-up after our dinner guests had departed.

When I served as external examiner in Aberystwyth and especially Lampeter, my lasting memory is of Birgitta’s and Laurie’s most generous hospitality in their beautiful Bronygaer. I was greatly appreciative of everything except the impressive array of inlagd sill at dinner. Laurie couldn’t believe that an alleged Swedophile simply called such delicacies ‘raw fish’.

Laurie’s research led to his doctoral thesis on Stig Dagerman, and Leif Sjöberg, the general editor of the prestigious Twayne Books series, was pleased to add it to their Swedish lists. Laurie very obligingly enlarged on his theme in ‘Swedish Prose in the 1940s’ a chapter included in Aspects of Modern Swedish Literature (published by Norvik Press in 1988), and much appreciated by our Honours students.

Laurie’s organisational and diplomatic skills were much in evidence in the setting up of Swedish Book Review. Jeremy Franks had for some time edited Swedish Books, a well-meaning but rather unsystematic magazine. After a suggestion from Franks that SELTA consider taking over the publication, Laurie secured backing from Kulturrådet, the Swedish Institute and the Anglo-Swedish Literary Foundation for a new periodical. Under Laurie’s editorship the first issue of SBR appeared in 1983 and it has gone from strength to strength. Meetings of the Editorial Board were relaxed affairs under his chairmanship, with some banter, not least between Laurie and Joan Tate, but he had the knack of persuading people to contribute. At one such meeting I suggested we should include a review section. ‘A very good idea. What are you going to call it?’ was his reply, and so Bookshelf was born.

Once Laurie retired from academia he had more time for his translation work, and this seemed to gather momentum as he fought defiantly against God and ill health. The Hexham branch of Waterstone’s had a section they called Scandicrime, and there in pride of place were Laurie’s versions of Mankell, Nesser, Åke Edwardson et al.

We had other things in common, including a love of cricket. I once pleased him when I said he looked rather like Colin Cowdrey, a splendid batsman, but alas, Cowdrey wasn’t a Yorkshireman, and Laurie, a loyal son of York, pointed out that England would never regain the Ashes if they didn’t have Yorkshiremen on the team. I said they were known to lose even with Yorkshiremen, but that, said Laurie, was because they had selected the wrong Yorkshiremen.

I saw little of Laurie latterly. He disliked cities and I seldom visited London after retiring. Almost once a year, however, we would coincide at the Gothenburg Book Fair – no need to make arrangements to meet, since I knew I could find him at the Stig Dagerman Society stall.

All those who knew him were delighted when Laurie was awarded the Order of the Polar Star in 1992. He was indeed a worthy recipient. He will be greatly missed in our field of activities, but he has left an invaluable legacy, not least over fifty translation titles and the admiration and affection of those who were fortunate enough to know him.

Laurie

by Peter Graves

Peter Graves taught Swedish and Scandinavian literature at the universities of Aberdeen and Edinburgh. Since he retired in 2008 he has been a full-time translator, concentrating in particular on Selma Lagerlöf and August Strindberg.

When thinking back on my memories of Laurie I came to realise what a very dodgy business oral history is: dates and decades slide together, distant past and more recent past tend to merge. Looking, for instance, at the handsome photographs of Laurie that accompanied various of his obituaries, my thought was ‘That’s what he looked like when I first met him.’ That couldn’t be so, of course, given that our first and not completely auspicious meeting was over forty years ago.

Sometime in the very early 1970s Irene Scobbie, who then headed the Swedish Department at the University of Aberdeen, decided it would be a good idea for British Scandinavianists to have a biennial conference and that Aberdeen should be the first to host one. Irene’s good idea more than bore fruit and for the next thirty odd years we had a series of stimulating get-togethers.

No one flew to conferences in those days, everyone came by train, so I was dispatched with a minibus to collect arrivals from the evening train. Aberdeen station is by the harbour which, pre-oil, was home to a large and largely alcohol-fuelled trawler fleet. Almost inevitably my minibus only had room for half the arrivals and I thoughtlessly deposited the other half in a harbour bar to await my return. When I reappeared three-quarters of an hour later to collect them they had fled from the bar out into the drizzle – and they were clustered around Laurie like chicks seeking protection.

That was the first, but certainly not the last, time I was on the receiving end of that characteristic widening of the eyes with which he expressed a mixture of lugubrious disbelief and world-weary exasperation. Study the obituary portraits and you can see a hint of that look still lurking there.

Laurie was, of course, anything but world-weary. I never worked with him formally but I met him at conferences, at external examinerships, at many meetings and many seminars – particularly at those wonderful annual weekend seminars he and Birgitta used to run for students and other guests at Gregynog. I was an invited guest at a couple of them, thereafter I simply invited myself. Every one of those occasions has a memory attached: the conference in Lampeter, for instance, which incidentally was by far the best of all of them, sticks in my mind because of Laurie’s joy at the cultural bewilderment the after-dinner penillion singer caused among the Scandiwegians, as Laurie referred to them collectively. And I was reminded of Gregynog when talking to my eldest son on the phone a few days before Laurie’s funeral. I told him I was on the way to Lampeter for a funeral and his first words were ‘ah, Cynddylan on his tractor’. I first saw R S Thomas’s wonderful poem ‘Ah, you should see Cynddylan on his tractor’ when Laurie organised a visit round the Gregynog Press, where they were making a poster poem of it. I took the poem home and it became my children’s bedtime mantra. Whenever you met Laurie you never failed to leave without a new author to look at, a new Swedish singer to listen to, or some new ideas for teaching. There was invariably something.

Laurie was always at the heart of things. Not in any pushy sort of way, because the last thing he ever was was pushy, but because people were drawn to him by his warmth, his enthusiasm, his huge cultural span and his droll humour. He cultivated a kind of gruff, no nonsense J.B.Priestley kind of Yorkshireness that was only half genuine: the genuine bit lay in his hatred of pomposity and bureaucracy – and particularly of the kind of inflated but empty language they encourage. But he was actually full of the best kind of nonsense: the wit and precision, for instance, of his after-dinner conference speeches – often produced late the night before – revealed a strong sense of the ridiculous. As did the late night emails he signed off as Hal. E. Lujah: the last email I got from him ended with the words, ‘looking forward to an early night tonight – must build up more strength ready for the Apocalypse’. Unfortunately, the Apocalypse came all too soon.

And what an organiser, or fixer rather. Who else could not only have kept Swedish alive in Wales through all those years in Aberystwyth and Lampeter, but actually have had more students of Swedish than anywhere else in the country? There was a very real sense in which, for a decade or more, Lampeter, that ‘strange little university on the edge of the world’ as David Austin has called it, was the beating heart of Swedish culture in Britain. Not only did it have more students, but it was the home of the Swedish Book Review that Laurie edited more or less single-handed for two decades. SBR served to keep us all up to date with what was going on in Swedish literature and to propagate that literature among publishers, and it was also the place many translators first saw themselves in print.

Ultimately it is the people who matter. Students were always central to Laurie’s understanding of what being an academic meant and he was a fine and stimulating teacher. He was also a stimulating colleague; as I said, I never actually worked with him but I have worked with several people who did and you always felt you had something to live up to.

There were, of course, things I didn’t understand. Why did he read The Daily Telegraph? Why did he want me to find out the names of the grounds at which the teams in the Scottish League played? These, and others, are things I’ll never understand. But what will always remain is his and Birgitta’s kindness. We all go through bad times – I did – and I discovered that it’s not only lame cats and hungry birds that were helped out in their home in Llanybydder; sitting in the garden there with a glass of chilled apple juice – in my case – is still the only place I’ve seen a red kite in the sky.

A Letter to Laurie

by Kerstin Abukhanfusa

When Kerstin Abukhanfusa worked with Laurie she was employed by the Swedish National Archives, in charge of publications and exhibitions. Collaboration passed into friendship and their correspondence lasted until Laurie laid down his pen.

Dear Son,

This will be my last letter to you. Written with sad heart and unsteady hand, because I know that you will never read it. Still, I want to write one last time. For many years we exchanged words, played with them, turned them inside out and enjoyed the sport. You were the master and it is only fair that you should have the last word. There is no word more unrelenting than silence.

You are not my son, nor am I your father. It began when I thought you were a lady. I told you then about my beautiful family name. That abu means father. What followed was an eighteen-year-long conversation between ‘Son’ and ‘Pappa’. That charade suited us both and added a kind of dissociation from reality. We both treated words as sharp objects which serve best when not veering too close to reality. I believe that was what drew us together.

Occasionally it required considerable effort to follow your twisted vocabulary. I did not know if you presented me with your own creations or were just showing off with conventional contortions. But it added extra flavour to our conversation that we could each use our mother tongue, and it certainly made it more playful.

In January 1998 I sent you a letter asking if you could help me with translations for a complicated exhibition catalogue. Next day you answered yes. For three days thereafter our correspondence focused on digital incompatibility. But before January turned to February we had begun to spike our letters with sarcasms. I started. Something told me that between you and me there were no communication problems – moreover, that you were a very kind person. Whereupon I told you the opposite!

Then we were off. We did not dig deep into the meaning of Life or how the World should be run. We kept to our own insignificance. So, what then did we write about? At the beginning work projects filled most of the space. As a colleague you were invaluable. With your help I finished my commissions successfully, and you never made my workload heavier by not delivering on time, as authors often did. Instead you made it easier by making me smile. And I could write back to you without paying the least attention to rhyme, reason or decorum, a blessing when frustrations were high. After the first year communication was the end in itself.

You then began to deliver hilarious portraits of ladies and gentlemen you met in academic circles, literary societies and a range of other ‘conventions’. They sometimes demanded a lot of imagination on my part, because your world differed a bit from mine. But the more artful the pictures you painted, the more I delighted in picking up the nuances. Then there were the cats! Terribly important family members who appeared in nearly every letter. When they suffered, words came closer to your inmost feelings than they usually did.

You were a bon viveur. Or wished to appear one. Delicious food and decent wine played a leading part in the good life you described. Usually I would make allowances. But why did your letters often arrive far into the night? Was it your deep sense of duty that forbade you to waste workinghours on unnecessary writings? Did all your friends receive late deliveries, or had you figured out that I am a night-owl? That was one of your pleasing idiosyncrasies, because I always fell asleep in a happy mood when I had digested one of your night-time messages, whatever the day had brought.

We only met twice. I kept threatening to descend upon you in Llanybydder, but when I was finally going to make good on my threat, fate intervened and forced you to direct your uncontrollable pen at a new set of victims. Despite the sad circumstances, your ‘horsepickle chronicles’ made me laugh. But time passed and the script became too long. Yet to the very end you kept words at a safe distance from cruel reality. Until there were no more words.

I miss them, dear Son! All those words we played with and turned into a bridge. A remarkably durable bridge. Now it is torn down.

Your make-believe Pappa in Nyköping, Sweden

Funny in Translation

by Rickard Fuchs

Rickard Fuchs is a doctor, writer, comedian and cartoonist. He has sold over two million books in Sweden, and his books have been published in twenty countries.

Laurie translated Have a Nicer Day (Prion, 2009) and You Don’t Look That Old! (Prion, 2011), as well as parts of several other works by Rickard.

I liked Laurie a lot.

He was warm and generous and had a great sense of humour. And in my case humour was especially important. The received wisdom is that it is one of the most difficult things to translate: the nigh-on impossible task of capturing a tone as well as getting across what the author actually means. And if humour differs from country to country, as is often the case, the wretched translator has to recast a strangely Swedish drollery in something naturally comic in English.

I used to say to Laurie, and to everyone else, that my books were better and funnier in English than in Swedish, thanks to Laurie’s translation – and I really meant it.

My collaboration with Laurie began in 1993. I have kept many of the faxes, and later the emails, that we exchanged. To start with they are rather formal in nature, but they quickly become more personal. Laurie wrote about what he loved, and about what he was thinking and doing. On 8 August 1993 he ended his fax with: ‘Curses! Even as I write, another English wicket has fallen to the Australians. Perhaps you have managed to avoid being smitten by the cricket bug, in which case you may find it difficult to understand why I shall now close in order to go away and contemplate suicide.’

On 18 September the same year he revealed his taste in television: ‘And in five minutes, the worst TV programme of all time returns to ITV. I love it. The worse they are, the more I enjoy them. Blind Date must be the world’s worst. I mustn’t miss it.’

And on 3 October he paid me the compliment of suggesting he might steal part of the speech I made at the Book Fair in Gothenburg to use at a translation conference in the United States.

Laurie and Birgitta’s cats often featured in his faxes and emails and on 19 October he indicated who it was, in fact, doing his job: ‘Time for tea break. Most of this fax was written by Blackie the cat (one of five who help me with translation and general computer work). If you notice a misprint or piece of bad grammar, that was Blackie, not me.’

Laurie was very generous and kind to me when it came to his fee for translating my texts. In an email of 4 May 2006 he writes: ‘Having just had to spend most of this afternoon begging outside the betting shop in Lampeter, following a bill for an allegedly major car service for over £520, I remembered that you owe me a fortune for a translation . . .’

In reality he must always have charged me substantially less than it should have cost. On another occasion when he had received my payment, he announced the glad tidings: ‘Even as I write that, The Call comes from downstairs informing me that grub is about to be served; I’d better go or I shall be beaten up. This is just a brief squeak to report that the cheque arrived this morning, so we might be able to eat this weekend.’

It was a true joy to have Laurie as a translator and a friend, and I miss him greatly.

Translated by Deborah Bragan-Turner

Laurie Thompson

by Philippe Bouquet

Philippe Bouquet taught Scandinavian languages at the Université de Caen. He has translated many well-known Swedish authors into French, including Björn Larsson, Kjell Westö, Vilhelm Moberg, Ivar Lo-Johansson, Stig Dagerman, Jan Guillou, Sjöwall and Wahlöö and Henning Mankell.

When reading Laurie’s obituary, I realised how much we had in common. He was one year younger than I am (almost to the day – 7 February 1937), we were both teachers (I don’t say ‘scholars’, my former colleagues would react strongly to my use of that word), we both received an honorary degree from Linköping University, nearly the same year (I in 1984, he in 1986; we could practically have met in the cathedral), we are both distinguished with the Royal Order of the Polar Star, we both have a son called Eric and we have several ‘victims’ in common: Mankell, of course, Aino Trosell and many more, certainly, among whom Dagerman is the most famous and meaningful. I have probably had more technical difficulties than he – since English is closer to Swedish than French is – but he certainly had publishers who were harder to convince, so det jämnar ut sig there also.

The difference is that although I have twice been on the verge of kola av – most recently last year – I am still alive. To what purpose remains to be seen. I decided that it was just so that I . . . could grieve for him as ‘another self’. I think we had the same goal in life: to make Swedish literature a little less unknown in the world. We both lived slightly apart from ‘the madding crowd’ and spent many thousands of days writing about, translating and speaking about Swedish literature. I’ll miss him – miss knowing that he is working ‘by my side’. But, as is the case with Mankell, I find solace in the fact that he’s had a very ‘full’ and gratifying life, and has achieved so much. Few people can be as proud of that as he.

Brevity, the Soul of Wit

by Håkan Nesser

Håkan Nesser is a former teacher who has become one of Sweden’s most popular crime writers, published in more than twenty-five countries.

Laurie translated eleven of Håkan Nesser’s books. The first was Borkmann’s Point (Macmillan, 2006).

As far as I recall, I met Laurie Thompson only twice, on both occasions in connection with the book fair in Gothenburg. Admittedly I lived in London for four years, but everyone knew that Laurie could not for the life of him see any reason to set foot in that city.

All the same, I thought I knew Laurie pretty well, because over the years we generated quite a lengthy email correspondence.

Laurie was extremely funny and extremely wordy. He often used the expression ‘I’ll be brief’, but always with a deeply ironic edge. In general, he ended his epistles with ‘Time to put him to bed. Hal E. Lujah’, and more often than not they arrived well after midnight. He was truly ‘brief’ only once. It was when we began working together; he had sent me a few chapters from the first of my books that he translated, I think it was Borkmann’s Point, and he was asking for my views.

I took it all very seriously, believing myself in possession of a decent grasp of the English language, and, in short, I supplied twenty or more comments, or, shall we say, reflections, on one expression or another, on this turn of phrase or that.

Laurie’s response came in a few hours and was six words long.

‘Håkan, I thought you knew English.’

Touché.

Translated by Deborah Bragan-Turner

Laurie Thompson

by Maria Rejt

When Maria Rejt first worked with Laurie she was Publishing Director of Fiction at PanMacmillan where, in 2010, she launched the Mantle imprint and continues as Mantle’s Publisher.

It was my privilege and good fortune to have worked with Laurie as the translator of Håkan Nesser’s landmark series of ten books featuring Inspector van Veeteren. I had been told during a visit to Poland with a group of publishers and translators that he was the very best Swedish-to-English translator and although it would be some years before we finally met, Laurie’s translations of Håkan’s intriguing, playful and existential crime novels were always pitch perfect. I don’t recall, over the eleven novels that Laurie translated for me, that they contained a single jarring phrase or expression. He always captured the complex narrative of Håkan’s novels, seemingly effortlessly, and their mood and essence, too.

When we did finally meet, over a lunch in Gothenburg, the occasion was a joy. Laurie was in his element: a brilliant raconteur, a wonderful conversationalist and a very generous person, it was obvious that he and Håkan shared a deep and enduring friendship. Back home, his emails were always a highlight in my working week. Usually sent around midnight, they were full of anecdotes, with a report on his progress hidden among the domestic detail and latterly, the news on his ‘medical adventures’ as he was fighting his battle with cancer. Not once did he complain.

Laurie’s most recent translation for Mantle, Håkan’s brilliant psychological thriller, The Living and the Dead in Winsford, was published to resounding critical acclaim immediately after Laurie died. He had, just a few weeks before, embarked on a new project for me, translating Håkan’s Inspector Barbarotti novels. Only two pages of his flawless translation exist, and it is immeasurably sad that there will be no more.

Goodnight, my friend, and thank you.

Gnat

by Christopher MacLehose

As Publisher at Harvill Press for twenty-two years, previously at Chatto & Windus and subsequently at MacLehose Press, which he founded in January 2008, Christopher MacLehose has brought to British readers many hundreds of books in translation. Swedish authors include Henning Mankell, Stieg Larsson, P.O. Enquist, Lars Gustafsson, Torgny Lindgren, Monika Fagerholm, and Kjell Westö.

The first translation MacLehose ever commissioned was of Henrik Tikkanen’s Brandövägen 8 Brandö. Tel 35, published by Schildts & Söderströms in 1975. Mary Sandbach’s translation, Snobs’ Island, was published by Chatto & Windus in 1980.

I knew Laurie as a translator. Also of course as a bird person, a cat person, a Yorkshireman and a Yorkshire cricket afficionado. He had also a lukewarm interest in English cricket in general. At his memorial service in the University Chapel in Lampeter not all of these key elements in his later life were given sufficient airtime, but what emerged from that beautiful service was a life, a ceaselessly working life, of such distinction, such generosity, and such scholarship as reminded me over and over again of how modest a man Laurie was.

As to birds, it should be added that the sheer scale of what the Thompsons put out to feed them was startling to behold. Laurie rejoiced at his limitless family of finches and tits that accepted their five-times daily bread, seeds, nuts. Almost as much as he rejoiced at his son Eric’s career and cherished family.

Generations of colleagues and undergraduates, graduates and postgraduates were deeply beholden to him. Many Swedish authors owed him their English readership; many Swedish publishers and agents thought the world of him, and the Swedish government had every reason to be grateful for his twenty plus years as editor of Swedish Book Review. He came to London at the end of that heroic term and collected a tea-set for his pains. That would be the last time he would come to London, he grumbled – he was a compulsive grumbler – and it was.

I have an idea that Laurie thought of editors in English houses for whom he translated somewhat as feral cats, badly in need, over time, of domestication. They really knew nothing of the work that a translator from Swedish (or German) does, can only guess, and yet will not hesitate – perhaps the eventually domesticated ones do hesitate – to make suggestions, even alterations.

Laurie was the wonderfully fluent translator of Henning Mankell, as all the world knows, although not the only one because who, after all, could keep pace with the tidal output of Henning’s stories? There were novels in different keys and the reality is that Henning in his headlong narrative mode was not first and foremost a stylist, but the English texts of the Wallander novels and stories that Laurie translated proved to be a joy to their hundreds of thousands of Anglo-Saxon readers. The Henning translation that I most admired was of a novel called Depths, which Laurie made into a very fine English novel.

Normally it is written that the one you set out to honour is already honoured with this and that royal decoration and academic degrees and no doubt has six pages on Wikipedia – I haven’t looked – but I want to put on record my absolute admiration for a man whom it was for two decades a very great pleasure to have known and learned from. And to say that his tireless work in all that time, his impeccable and punctual texts, his truly extraordinary modesty and sweet nature in the face of a workload that would have flummoxed a scholar half his age, were exceptional. He worked, under the gracious care of Birgitta, so far as pretty regular exchanges of emails gave me to understand, all morning, all afternoon and all evening, until almost midnight and then a message would come, signing off, with ‘Wild Welsh grunts. Gnat’.

The Swedish for Snow Angel

by Becky Toyne

At the time Becky Toyne worked with Laurie she was an editorial assistant and later an assistant editor at The Harvill Press. She now lives and works in Canada, where she is a freelance books columnist, literary event publicist, and, yes, still an editor of crime novels.

Åke Edwardson’s Sun and Shadow, translated by Laurie, was published by Harvill Secker in 2006.

When I took the first few tentative steps in my career in publishing, fresh off the back of an English literature degree, if you had told me that the bulk of my days would be taken up with the publication of Scandinavian crime novels, I would have thought you were cuckoo. And yet, when I landed a job as an editorial assistant at The Harvill Press, that’s what came to pass. Publisher Christopher MacLehose was a fan of detective stories, and had been building a list of European crime writers in English translation. Among the list was an increasingly popular contingent of Swedes and Norwegians, with Henning Mankell leading the charge. And so it was that Laurie Thompson, a translator of Henning Mankell’s Kurt Wallander novels, became one of the early influences in my literary life.

Though I was young and still very green, Laurie approached my questions (some of which were almost certainly irritating) with patience, and considered my opinions with respect. I learned from him much about the careful, interpretive role of a translator. I also learned that translators ought to be paid much more than they are. I remember with great fondness the time I travelled by train from London to Wales to stay with Laurie and his wife Birgitta. I was editing Laurie’s translation of Sun and Shadow by Åke Edwardson at the time, and we sat at a table in a light-filled sunroom with piles of scribbled-upon manuscript spread around us. During that long working session in which we each won and lost some linguistic battles, he taught me about reading a scene aloud to help you arrive at the right answer. He taught me that sometimes the best thing to do is just to let it stand. I taught him that the English term for what Swedes call a ‘snow angel’ is . . . ‘snow angel’.

Laurie loved cricket, though his conversations on the subject with Christopher may as well have been in Swedish for all I ever understood of them. He had a gentle manner, a kind smile, and a wry sense of humour. He also, it must be noted, had excellent eyebrows.

Tack så mycket for all the wisdom, Laurie. Tack så mycket.

'This will be a short reply . . .'

by Barry Forshaw

Barry Forshaw is a writer, broadcaster and journalist whose books (apart from those mentioned here) include Euro Noir, The Rough Guide to Crime Fiction and the first biography of Stieg Larsson.

I once asked the Swedish crime master Henning Mankell whether he discussed with his translator Laurie Thompson the kind of book the next one would be; did they talk about approaches and so forth? Mankell shook his head and replied firmly: ‘I don’t need to. I absolutely don’t need to – I trust him completely. My books are translated into so many languages, it would be impossible for me to check every one. But I do try to make a point of checking those languages that I can check – and it’s only on one occasion that I have rejected a translation (it wasn’t in England – it was in the United States). The language the book was in was not something that I recognised as mine. But that would never happen with Laurie.’

The entertainingly sardonic translator of Mankell and Håkan Nesser (who also praised Laurie – he recently told me in London how sad he was to hear of Laurie’s death), was someone I always personally found to be a fund of often unsparing insights.

‘As you know,’ Laurie once told me, ‘I’m not a crime specialist, and my involvement in Swedish (not Scandinavian) crime novels is accidental. I didn’t watch The Bridge or Borgen; I did watch the last couple of Kenneth Branagh Wallander adaptations, and thought they were awful. Some of my most rewarding connection with Swedish crime novels lately has been via Håkan Nesser and Åsa Larsson – frankly, I think she’s better than her male namesake.’

I noticed that one particular Swedish writer (a regular visitor to, and sometime resident in, the UK) was frequently returned to in my conversations with Laurie – clearly a favourite of his. ‘I enjoyed working on a Håkan Nesser novel,’ he told me, ‘called in Swedish “Ewa Moreno’s Case”, but called The Weeping Girl in English. It’s a typical Nesser novel, full of linguistic jokes and amusing banter between police officers, not to mention quite horrific happenings, but it also raises questions about the human condition and human shortcomings. For me, this is why I think Håkan is a brilliant writer – one can appreciate and enjoy his novels without realising all the subtleties, but if you do, then he becomes even better!’