At Your Side

The Role of Literary Agents on the Swedish Market

by Elin Klemetz

photography by Samuel Petersson

translated by Ian Giles

Back in the day, literary agents sold your book to international markets – now they want to represent you in every situation imaginable. But what do they actually do? And is having an agent always in your best interests as an author?

This article was originally published in Swedish in Skriva,10 October 2022. See how Swedish agencies work with authors at different stages of their careers in Help Wanted, a guide published alongside this article.

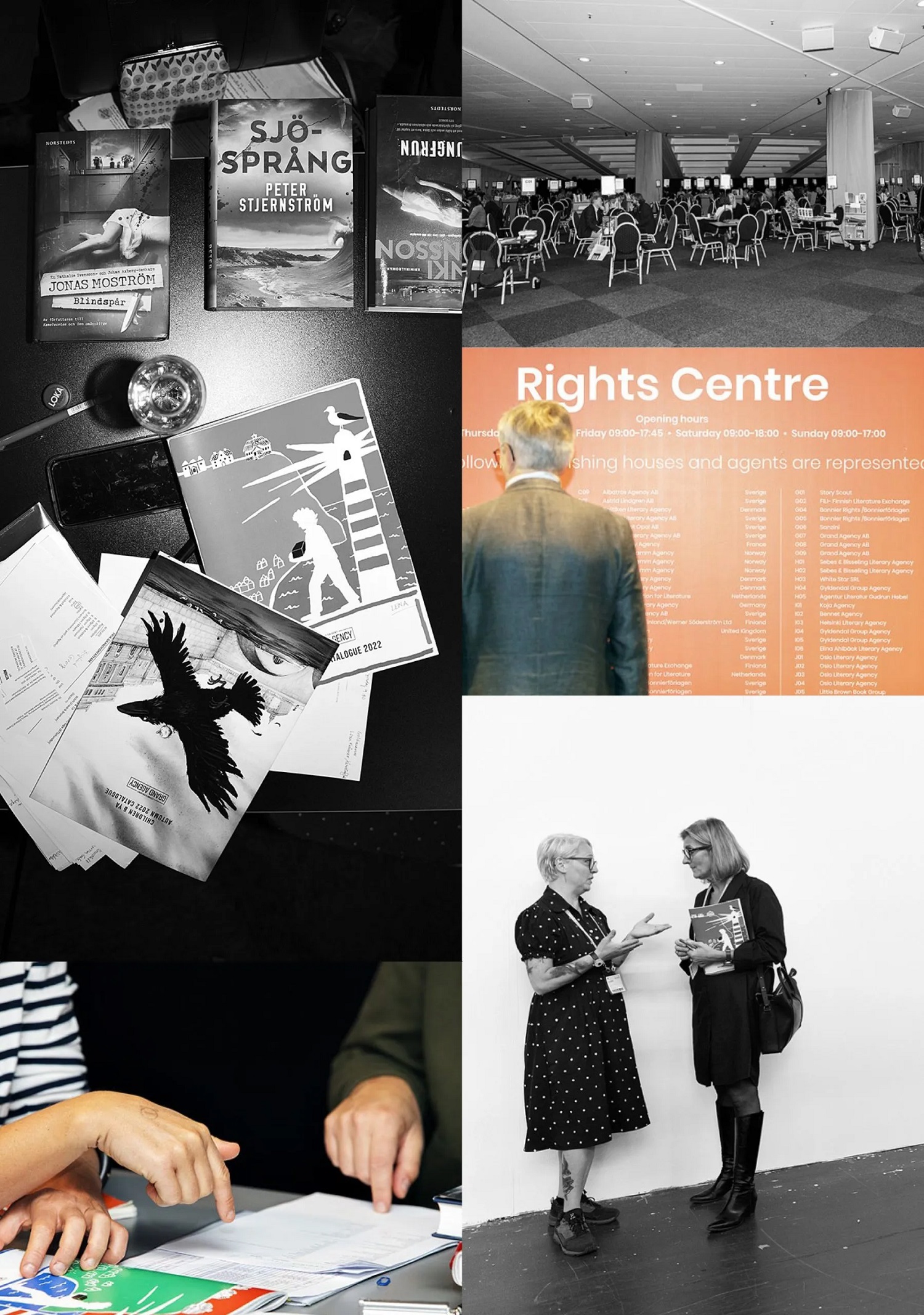

In a room shrouded in a degree of secrecy on the fringes of the Gothenburg Book Fair, the scene resembles a speed dating event: a series of engaged conversations, often one-on-one, are taking place at eighty or so small white tables all adorned with red signs. Lena Stjernström gets up from her seat at a table marked ‘Grand Agency’. She checks the time. 09:35. Her next meeting should have started by now – the half-hourly changeover basically runs all day – but the Finnish publisher due at 09:30 is delayed. Oxygen levels in the crowded space are already low. Stjernström hurries into the lobby area of the Rights Centre, sips water and takes a few deep breaths. She returns to receive Cristina Gerosa, the publishing director at the Italian publisher Iperborea. They greet each other with cheek kisses – a custom that has survived two years of cancelled fairs due to the pandemic. Stjernström pulls out her catalogue and begins to talk about Jenny Jägerfeld, who Iperborea already publish, and her YA novel My Royal Grand Golden Love which comes out this autumn. Gerosa listens with interest, jotting away in an orange notebook.

‘Oh, she’s fantastic! Everybody adores her.’

A noticeboard inside the Rights Centre shows that there are more than 50 different businesses present – primarily agencies from the Nordics and Europe. I make the Swedish agency tally 17, of which about half are owned by publishers and the remainder are independent. Those companies in the latter category also work to sell their authors in the domestic Swedish market – something which was previously uncommon. Today it has become – especially among genre fiction authors – more or less a matter of course to consider engaging an agent when sales figures increase.

But the expanded role of agents is not appreciated by all.

Literary agents have operated in Sweden for decades, but in the beginning their desks were found inside publishing houses. The first standalone firm, Nordin Agency, was founded in 1990. Before long they came to play their part in creating international hit successes such as Camilla Läckberg and Viveca Sten, and it was the emergence of ‘Nordic Noir’ that saw the space for literary agents expand significantly. The major publishers formed their own agencies, including Bonnier’s Bonnier Rights, while the 2000s saw an increasing number of independent agencies joining the scene.

Stjernström and her husband Peter founded Grand Agency in the middle of the rush in 2007. Both came from marketing backgrounds – Lena had originally trained as a political scientist and had spent many years working in the aid world when she opted to change tack and launch her PR firm Full Tank with Peter. Since the couple felt the best part of the job was organising events on behalf of the book industry, they decided to move in that direction. Together with Maria Enberg, who had at that time just left Nordin Agency, they connected with emerging bestsellers such as Anna Jansson and Mats Strandberg.

A number were particularly successful abroad. Lena remembers a German publisher at the Frankfurt Book Fair seizing a flyer about their recently signed author duo, Cilla and Rolf Börjlind, whose debut was about to come out.

‘They wanted to buy the book without even reading it. We didn’t let them – we wanted them to wait until the manuscript was ready in February. But it ended up being the same publisher that bought the rights in the end – the morning after we sent it out.’

These kinds of hyped foreign rights sales are presumably what many picture when they hear the words ‘literary agent’, but nowadays independent agents also represent authors in the Swedish market.

‘The very foundations of an author’s body of work are in Sweden, so we want to be on board and work here too,’ Stjernström notes.

The task at hand in Sweden can entail negotiating royalties and providing guidance around the publishing process, as well as offering support if an author falls into conflict with their publisher – a situation where authors can feel quite small and excluded.

‘The stuff that authors find boring is the stuff we really enjoy: negotiating and pushing the industry to modernise and to make contracts more favourable to the creators,’ says Stjernström.

In 2013, when colleagues Peter Nyström and Peter Mohlin finished their first co-authored thriller manuscript, it was still unusual for debut authors to turn to an agent. Despite this, the duo agreed that an agent would maximise their chances, and they quickly got a bite. But after that, things didn’t go quite as they had expected: not a single publisher wanted to acquire their book.

‘It was a major setback. They’d built up our expectations. “This is the next big thing. It’s so damn good.” But then everyone said no,’ Nyström explains.

After crawling out of their pit of disappointment, they were still able to conclude that taking on an agent hadn’t been an altogether bad decision.

‘The publishers told the agents what shortcomings they had identified in our manuscript without any filter. We asked to see what they had said, which did us the world of good. I don’t think we would have been able to access that feedback by any other means,’ says Nyström.

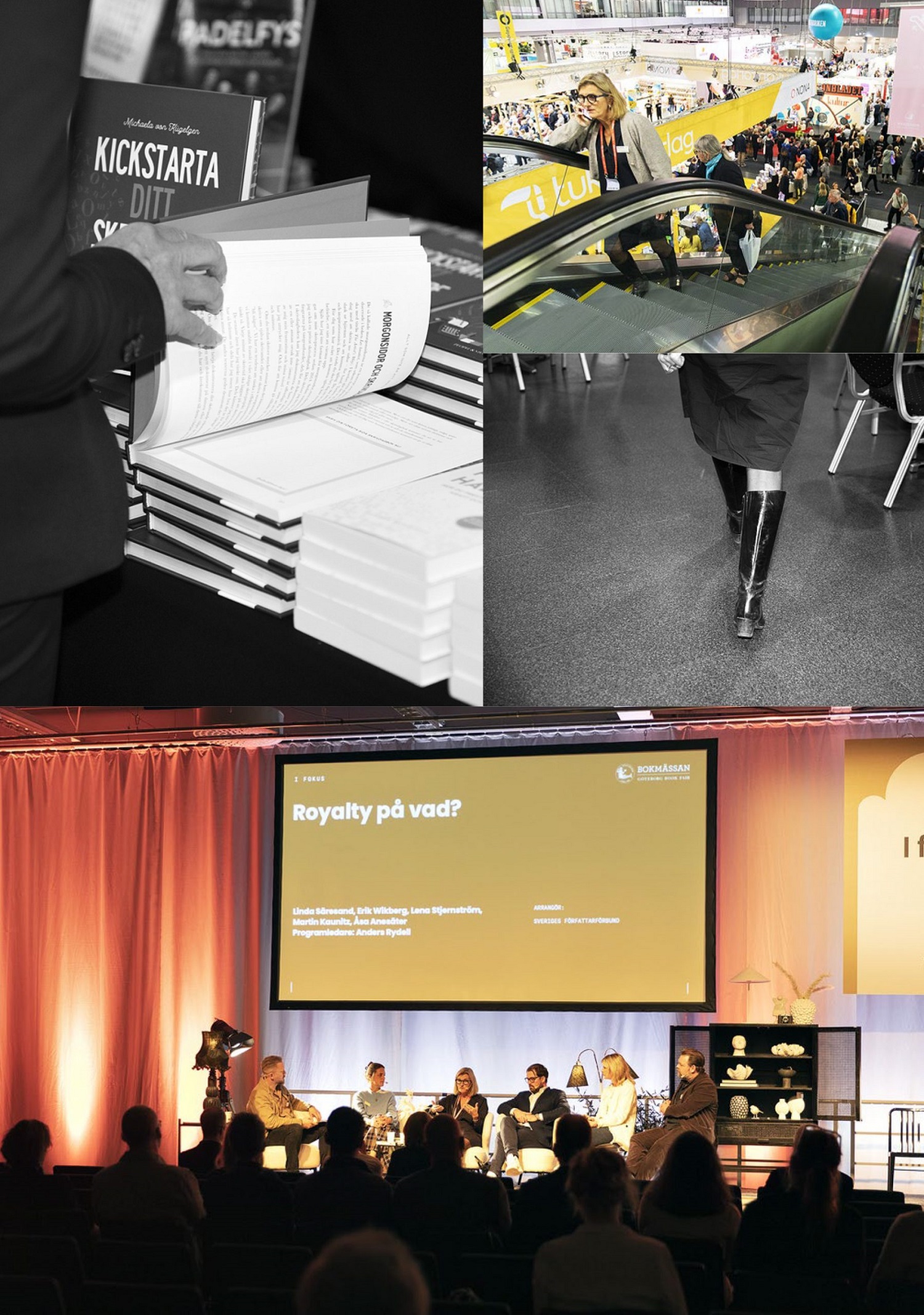

Five years later, when Mohlin and Nyström put the finishing touches to their new manuscript, they noticed there were more competitors to contend with – they had to wait longer for a response from the agencies they submitted to. When they eventually signed with Nordin Agency, both Albert Bonniers and Norstedts made offers. Norstedts won at auction, and The Bucket List was published in Sweden in 2020. The book won the Crimetime ‘Debut of the Year’ prize and has now been translated into more than 20 languages.

‘When it came to signing the contract with the publisher, we realised we had no clue what kind of advance we should be asking for,’ Nyström says. ‘Without the agency, it would have felt like selling a house without an estate agent.’

He considers it to be highly advantageous that they don’t have to negotiate their financial terms with their publisher.

‘With Norstedts, we only want the good stuff: creative encounters. We’re keen to avoid being the guys who say: “No, we want more cash.” I think we would have been lost without our agent. Of course, your agent takes a cut, but do you actually end up with less money in the end? Without an agent, our books might have come out in Sweden, Norway and maybe Denmark – at best.’

Mohlin and Nyström’s agent negotiated with publishers around the globe, as well as selling an option on the book to a film producer.

‘And those contracts are nigh on impenetrable. There were something like 35 clauses that might as well have been in Greek. Our agent was worth their weight in gold there.’

Of course, the relationship can vary, says Nyström.

‘When we compare notes with other authors who are with other agencies, there are differences in how much help you receive as writers, and how much time the agents spend on you. In the end, I suppose it depends on how well the books sell. Thankfully, we haven’t ended up in that situation, but we have mates who say: “Bloody hell, we’re not hot anymore. We’re calling our agent more than they call us...”. That was how we felt with our first book.’

Spotlights illuminate a stage decorated to resemble a living room: beige, upholstered armchairs, a marble-patterned coffee table, and a small black bookcase which – despite being at a book fair – is filled with white knick-knacks. Shining on the wall behind the five panellists – all of whom work in the industry – is the projected title, ‘Royalties on What?’. Anders Rydell, editor of the Swedish Writers’ Union’s magazine Författaren, perches on the edge of his armchair, facing Lena Stjernström.

‘In an op-ed, you wrote: “Now it’s time for the dividends to be paid.”’

‘Yes, those of us behind the piece feel that that there was a happy-go-lucky mood in the air,’ Lena replies, before continuing:

‘It was such a thrill when audiobooks began to take off that we didn’t really clock that the remuneration per book listen is too low.’

Audiobook remuneration is one of Stjernström’s hobby horses. As an agent, her job is to negotiate contracts individually on behalf of her authors, but it is also in her interests to influence developments on a broader level. Naturally, this is something the Swedish Writers’ Union finds gratifying.

‘We’re keen to have a good relationship with agents,’ explains Grethe Rottböll, Chair of the Swedish Writers’ Union. ‘We share common interests – such as audiobook remuneration. The agents are great at negotiating higher levels of royalties, and it’s good that we can communicate with each other to boost rates for all authors.’

At the same time, she does identify a potential downside: wherever there is cake, it goes without saying that those with literary agents get a bigger slice. And that leaves less for everyone else.

She also stresses that it is important for authors to be aware of which rights they allow an agent to work with.

‘For example, when it comes to film rights, you should find out whether your agent knows anything about film, and whether they have sufficient contacts to be able to secure a good deal. If they don’t, our view is that authors should retain film rights themselves. In terms of the bigger picture, it’s important to figure out whether you can recoup the cost of the agent.’

Publishers are also to some extent sceptical about whether authors need agents – especially in the Swedish market. Håkan Bravinger is Literary Director at Norstedts – a publisher that not only has its own in-house agency (Norstedts Agency) but also maintains ongoing contact with all the major independent agencies in Sweden.

‘Agents reach out to us when they have something they think we ought to read, but we also keep our channels open to discuss the authors we already work with. Sometimes we might be looking for something in particular that we think is missing from our lists.’

He won’t comment on whether standalone agents are a positive thing for publishers and authors.

‘But it is important to understand that an agent is working on behalf of the author. If the author wants someone to represent him or her and is willing to pay for it, then that’s no problem as far as we’re concerned. Although when it comes to the Swedish market, we do sometimes wonder why authors who have a good relationship with their publishers and pretty straightforward contract negotiations still opt to hire an agent who takes 10-15 per cent of their income in return for very little work.’

Zandra Weldon, from the smaller publisher Lind & Co, which lacks its own in-house agency, feels more or less the same:

‘I don’t really see what need there is for an agent in the Swedish market. Our contracts are all the same – we don’t hold something back just because you don’t have an agent. In fact, it can end up being more work if there’s an agent involved. It’s yet another person who has to have their say on the jacket design or the manuscript.’

One argument the agencies highlight is that, if an author is in any way dissatisfied with their publisher, an agent can help them to find a new one. Norstedts’ Bravinger feels this can be a double-edged sword for authors.

‘It takes quite a lot for us as publishers to terminate our relationship with an author if we’ve worked hard to build up their body of work. But if there’s an agent involved who is happy to fish around other publishers, then it’s also easier for us to cut ties and just look at it from a financial perspective. There just isn’t the same bond. With an agent as middleman, it becomes more akin to pure business – of course, that may suit some authors.’

On their part, agents argue that the loyalty shown by publishers to their authors has also deteriorated – so the latter are in greater need of someone to negotiate on their behalf.

Maria Enberg has been watching these developments since the very beginning. She was part of the team that built the Bonniers press department in the 1990s, before going on to work at Nordin Agency and helping to launch Grand Agency. In 2016, she moved on and founded Enberg Agency with her daughter.

‘In the past, both publishers and authors were more faithful to one another,’ says Enberg. ‘Now everything is messier – just because you’re currently with one publisher doesn’t guarantee that they will take your new book. More people are writing in multiple genres in order to make a living from their work. And there’s no guarantee your book will sell abroad. For instance, the in-house agency at Bonnier handpicks which books they want to sell translation rights to, and don’t give any backing to other titles. An independent agency can focus on you as an author in a completely different way.’

So what does it take to hook an agent? Lena Stjernström remarks that they have to like the manuscript, like the author, and believe there is commercial potential.

‘It’s the nature of the beast that we are most frequently engaged by authors who write in commercial genres since those books are the ones that most easily export. It costs in the region of SEK 100,000-150,000 for foreign publishers to translate a book. If they buy a less mainstream title, it may not sell more than a few thousand copies. But if they manage to sniff out the right successful crime fiction series, they know they can shift 10,000-30,000 copies in the larger foreign markets, such as Germany.

Crime fiction often does well, although it is no longer as self-propelled as was the case in the Nordic Noir heyday.

‘Foreign publishers are no longer clamouring for Swedish whodunits. On the other hand, it used to be impossible to sell Swedish feelgood novels, but now that’s a massive trend. The criteria for getting a book published by a publisher abroad are in some respects the same as in Sweden – there has to be something unique in the narrative, a compelling character or a new theme – but there’s more to it than that,’ says Edith Enberg Salibi of Enberg Agency.

‘For example, there should ideally be a Swedish connection such as Swedish characters and settings. A big mistake debut authors can make is to think that their novel needs to be set somewhere else if they’re to sell abroad. But that’s rarely a success factor.’

Non-fiction books can also do very well. Thomas Erikson’s Surrounded by Idiots is represented by Enberg Agency and has now been translated into 48 languages.

What makes a book interesting to the film and television industry has also changed over the last decade, says Enberg Salibi, who previously worked for the Swedish production company Tre vänner, including a production assistant role on the 2013 movie Easy Money III: Life Deluxe.

‘In the past, they would only be after books that had sold 200,000 copies. Now we’re finding they aren’t all that fussed about sales figures. The most important thing is good stories.’

Lena Stjernström raises her glass. ‘Cheers everyone!’

Grand Agency has organised a get-together in a corner of the West Coast restaurant next door to the Book Fair following what has been a sweaty day of work inside the exhibition centre. Authors, publishers and colleagues chat and laugh together. The mood is relaxed.

Stjernström points out that personal chemistry is an important factor when they consider a new author.

‘Both we and the author need to feel it’s right. They’re entrusting us with a great deal. They need to be able to trust us, and vice versa.’

Crime writer Jonas Moström has his champagne flute refilled and approaches the table of salted almonds and charcuterie. He joined Grand Agency following a less positive experience at another agency.

‘There wasn’t the greatest of engagement there – not in terms of communication or results. There was a change in owners, and I guess I slipped through the cracks. Here I’ve experienced a different kind of openness and enthusiasm. I often discuss titles, covers, and even the plot with my agency.’

Moström reckons he makes back the fee charged by the agency for their services.

‘Maybe not in Sweden alone, but across the board, yes. Besides, I’ve no interest in the financial side. It would take an enormous amount of my time to stay on top of things and crank out the percentages the way they do.’

It is hard to tell what role literary agents will play in Sweden going forward. Few think we will see the same trend that has taken hold in the UK and USA, where unagented authors no longer have any chance of being taken on by publishers. Indeed, there are indications the opposite might be true. As companies such as Storytel become international and seek to translate and publish audiobooks and ebooks themselves in other countries, they circumvent both agents and publishers.

‘That’s definitely a challenge. It’s daunting, but also kind of exciting,’ says Maria Enberg of Enberg Agency.

But both she and Lena Stjernström believe more authors will require representation in future.

‘In a globalised world of streaming services and bestsellerism, it’s vital to have someone on your side looking out for your interests,’ says Stjernström. ‘It’s really hard for an author to build up that kind of network by themselves and keep track of industry trends. After all, an author needs to focus on writing their books.’

THE AGENT’S TASK

A literary agent represents the author in a range of business relationships. Among other things, agents can:

- Sell rights to foreign publishers. This happens at book fairs. The annual Frankfurt Book Fair is one of the most important in the industry, and features a large rights centre where agents set up meetings with publishers. Agents also maintain ongoing contacts with publishers and literary scouts overseas.

- Handle negotiations with your Swedish publisher/s. Just like in other negotiations, this focuses on the extent of the rights granted and royalty levels. On occasion, agents might help authors to find a new publisher. In cases where an agent represents a debut author, the agent’s primary task is to secure a Swedish publisher.

- Sell film and TV rights. Production companies usually buy options on manuscripts – this means they pay a fee to allow them to explore the option of making a film adaptation for a set period of time. Should such a project be realised, a significantly larger amount will be paid.

- Negotiate with companies that publish books in other formats. The agent may, for example, negotiate audiobook and podcast rights with streaming services such as Storytel and Spotify, or rights relating to ebook publication.

What agents don’t do:

- They aren’t responsible for your text. An agency may have thoughts and suggestions on how to improve your manuscript, but it is the editor at your publisher whose main task is to focus on your text.

- They aren’t responsible for PR related to your books in Sweden or abroad. Agents are happy to make suggestions around marketing, exposure, and an author’s profile, since good sales are in their own interests. But publishers handle this and are responsible for marketing books.

Skriva

We are grateful to Skriva for granting permission to publish this translated article.

Skriva is Sweden's only magazine about writing, with a circulation of around 40,000 readers (as per ORVESTO, 2022), including professionals, students and amateur writers. Skriva also organises courses and writing contests, and curates the stage Café Skriva at the Gothenburg Book Fair each year.

Elin Klemetz is a freelance journalist and editor based in Gothenburg. She works mainly in the areas of literature, culture and spirituality. Follow her work on Instagram: @elinklemetz.

Samuel Petersson is a photographer and filmmaker based i Gothenburg. Follow his work on Instagram: @samuel.petersson.

Ian Giles has a PhD in Scandinavian literature from the University of Edinburgh. Past translations include novels by Arne Dahl, Carin Gerhardsen, and Camilla Läckberg. He is Chair of the Swedish-English Literary Translators’ Association and lives in Edinburgh.