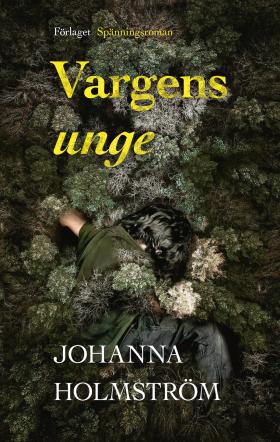

Vargens unge

(Wolf Cub)

by Johanna Holmström

reviewed by Darcy Hurford

Depictions of life during the pandemic have seeped into many recently published novels, yet most of them seem to use it as a backdrop to their stories, as detail to anchor the story to a particular time. Wolf Cub goes one further; it uses covid restrictions as a plot device to accelerate events. When the pandemic breaks out, the fictional ecological community of Toivola at the centre of the novel becomes even more isolated. This suits Gloria Hammarström just fine – at least to start with. She is a photographer from Helsinki who has recently joined the community, together with Luukas, her son from a previous relationship, attracted by the alternative style of life. She is now head over heels in love with Aaron, another community member. Pandemic restrictions mean travel to and from the region around Helsinki is restricted, so Luukas’s father and Gloria’s family are less able to get involved and spoil things. At least for a while.

The pandemic restrictions also suit certain members of the community, who stage a de facto coup and oust its original leadership, imposing their own rules on how to deal with the situation. The community will look after its own sick, which seems fine – until someone dies of covid. To start with, Gloria is so loved up she isn’t really concerned. Her family stage an intervention and take Luukas back to Helsinki. Only as the new regime destroys her relationship with Aaron does she start to realise what’s going on – and that she needs to escape.

Gloria’s story starts in 2019. The novel opens in the present, or fairly close, in May 2023 when a retired couple, Seija and Tarmo, finding a very young child outside in their garden. They live in Kuhmo, a small town located about half-way up Finland and bordering Russia. They take the boy in and contact the police (reluctantly, as there is history between Minna Salminen, a local police officer, and Seija and Tarmo). Finding out where he has come from turns out to be complicated, as he doesn’t seem to speak Finnish and there is no official record of his existence. They find a memory stick in the child’s mouth. When examined, it holds images suggesting murder has taken place, making it all the more acute to find out where the child’s caregivers are.

Wolf Cub was serialised over 57 episodes in the Swedish daily Dagens Nyheter over the summer. It was a great choice, as this is a thriller with several plot strands, plenty of tension and several twists in the tale. The theme of a remote alternative community and the problems it causes children in particular are slightly reminiscent of Annica Norlin’s The Colony (Stacken) (reviewed in SBR 2024:1), but things here are much more deadly. The perspectives are mainly female: we see the story through Seija, Minna or Gloria’s eyes, much less often through anyone else’s. Importantly, space is given to the character’s emotional responses and how they process what happens to them.

There are explicit references to Finnish folklore, namely the Kalevala, with characters such as Louhi and Ilmari. ‘Toivola’ means ‘place of hope’ in Finnish, so there is a sad irony to its decline. People are spied on, filmed and kept isolated from the outside world, and when two Ukrainian refugees arrive and are taken in, it is not long before it becomes horribly apparent what the community’s leaders are capable of. The Ukrainians meet a macabre fate, the kind of extreme gore that makes you wonder if the author’s over-doing things even though you realise that yes, it’s probably happened somewhere in real life.

At the same time, Wolf Cub is of a high literary quality. You could read it twice: once, zipping through it as a page-turner, to follow the plot and find out how it ends, then a second time, more slowly, to appreciate the finer points. Holmström has a fine eye for the details of human relationships. Minna is worried about her husband’s jealousy of her male colleague Timo (nothing erupts, possibly because she puts constant efforts into avoiding it), while Gloria’s role as the black sheep of the family becomes all too clear when her family in Helsinki appear in the story. The closing chapter brings together the emotional effect of everything that has happened and ends on a note of cautious optimism.

Vargens unge

Förlaget M, Finland / Albert Bonnier, Sweden, 2024

428 pages

Foreign Rights: Elina Ahlbäck Agency

Johanna Holmström debuted as an author in 2003 and has won awards in both Sweden and Finland. An extract from Island of Souls in Fiona Graham’s translation appeared in SBR 2019:1 and was reviewed in SBR 2018:1. Lucid Dreams: A User’s Manual was reviewed in SBR 2022:1.