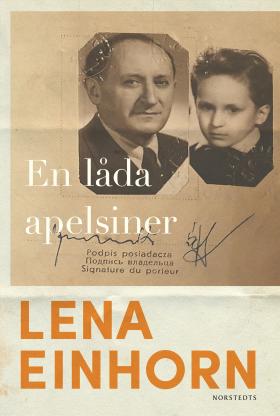

En låda apelsiner

(A Crate of Oranges)

by Lena Einhorn

reviewed by Fiona Graham

As a journalist, writer and editor-in-chief of Sweden’s Judisk Krönika (Jewish Chronicle), Jackie (Joachim) Jakubowski was an important figure in Swedish literary and cultural life for several decades. Yet he was never to write the story of his early life in Communist Poland. Chancing to meet author and film-maker Lena Einhorn (also of Polish-Jewish parentage) in Tel Aviv, he talked about his dramatic childhood, teenage years and early adulthood with unusual openness, prompting her to ask: ‘Jackie, shall we write a book about this?’ Jakubowski replied that he was the only person who could write such an account. Yet three years later, stricken by the illness that was to end his life at just sixty-nine, he decided to entrust his story to Einhorn.

In the late 1960s, an anti-Semitic political campaign under Communist Party leader Władysław Gomułka made life increasingly intolerable for Poland’s small remaining Jewish community. From 1967, Polish Jews emigrated in their thousands to escape harassment and persecution, as most recently documented in Daniel Schatz’s Forgotten Exodus project (forgottenexodus.org). Sweden offered refuge to many: those who would later commit their experiences to paper include Emilia Degenius in her heart-wrenching memoir Åka skridskor i Warszawa (Skating in Warsaw, 2014) and Maciej Zaremba, whose outstanding, genre-defying work Huset med de två tornen (House with Two Towers, 2018) covers a broad sweep of Polish twentieth-century history. Among the emigres who made their way to Sweden were eighteen-year-old Joachim Jakubowski, then known as Jasio, and his gravely ill father Stanisław (Staś). Within a year, Jasio would find himself alone in his new country.

Einhorn maintains tension by revealing the key facts little by little, forcing the reader to fill in the gaps. While the greater part of the narrative follows Jasio’s life in chronological order from early childhood, there are also flashbacks to chilling scenes involving two sisters in wartime and immediate post-war Poland, and ‘flash-forwards’ to Jasio and Staś’s arrival in Sweden. We do not discover why Jasio and Staś are alone until well into the story, and the full, startling truth is revealed only in a climactic meeting at the very end.

One poignant scene follows another in the main narrative, depicting Jasio’s childhood. Sent to the mountain resort of Zakopane to recover after a hugely traumatic event, six-year-old Jasio draws a line of aeroplanes with the Polish flag. Why not the flag of ‘the Holy Land’, asks the overbearing man in charge, before purposefully ripping the child’s drawing to pieces. The innocent six-year-old has no idea why. But he dimly grasps that he is regarded as different from the other children and begins to internalise this sense of difference. When he starts wetting the bed, a worried Staś takes him to a psychologist who addresses him in medical jargon and administers electric shocks. On his first day at primary school, Jasio finds he is the only child who can already read. Yet this unwanted distinction pales into insignificance beside his ignorance of the uplifting Communist song which, so it seems, all the other children know by heart.

Staś is a loving father, but not always easy to live with. A dapper ladies’ man fond of dancing, he is rather lacking in domestic skills. His cooking relies mainly on eggs and onions: the latter, so he claims, contain everything necessary to maintain human life – a puzzling statement whose significance emerges much later in the narrative. Officially, he repairs clothes for a living, but has a sideline in bespoke ladies’ coats which have to be delivered on the quiet; private initiative is proscribed under the Communist regime, though others, like the family of Jasio’s friend Wojtek, have the right connections to bribe their way around the rules.

Jasio/Jackie’s boyhood is depicted through the eyes of a sensitive and intelligent child who, while not always understanding the full context, has a strong sense of what is just and unjust, accepted or not accepted. He delights in the sensory magnificence of the Catholic church he attends with kindly Halina, who befriends them when Staś begs her for help with cooking. But he knows this must be kept a secret from his father. Even within the Jewish community, there are insiders and outsiders, those who receive the titular crate of oranges from Israel, and those who don’t.

After emigration to Sweden, Jasio/Jackie cared for Staś until the latter’s death, qualified as an electrical engineer to honour Staś’s wishes, and rapidly found his métier as a writer – in a language he had only started to learn at eighteen. In her engrossing account of how Jackie Jakubowski grew to maturity under the most trying of circumstances, Lena Einhorn has done full justice to this remarkable man.

En låda apelsiner

Norstedts, 2023. 325 pages.

Foreign rights: Hedlund Literary Agency, Magdalena Hedlund.

Lena Einhorn’s recent works include the historical novel Geniet från Breslau (The Genius from Breslau, 2018), reviewed in SBR 2019:1; A Shift in Time (2016), which examines parallels between the New Testament and contemporaneous texts; and Blekingegatan 23 (2013), a fictionalised account of Greta Garbo’s early life. For full details of Lena Einhorn’s works, see her official website: lenaeinhorn.se/English.

Emilia Degenius’s Åka skridskor i Warszawa (Ersatz, 2014) was reviewed in SBR 2015:1. Maciej Zaremba’s Huset med de två tornen (Weyler 2018), was reviewed in SBR 2019:1.